Silverio and memoryless Seville

Silverio was the master of his time, the great flamenco personality who earned the respect and admiration of gypsies and not-gypsies alike, having a crucial role in the professionalization of flamenco

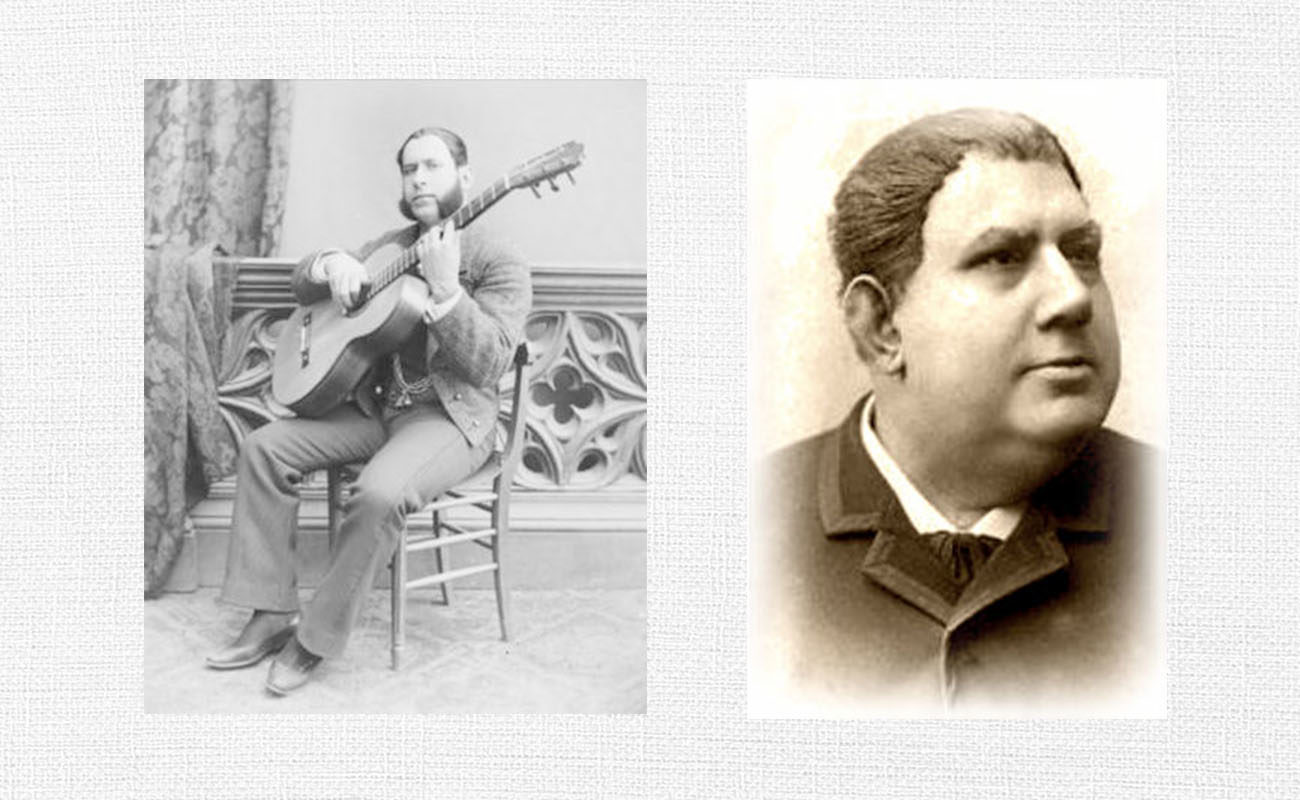

Silverio Franconetti Aguilar (Seville, 1830-1889) is the most influential flamenco cantaor and the most important personality in the history of this art. Thus, it’s unacceptable that he has been forgotten by Seville, a monument-prone city, where there is nothing in his memory. Silverio was a prodigy of cante, and among his teachers there were both gypsies and non-gypsies, even as it’s often said, with no basis at all, that he was taught by El Fillo when he visited Morón de la Frontera, the town in the provice of Seville where the genius with the Italian surname grew up. When his father Nicolás Franconetti Chesi passed away, his mother, loaded with children and with financial problems, decided to seek help from her firstborn, Nicolás, who had opened a tailor shop in Morón. It was there where Silverio had his first contact with cante. There, and also in Marchena, where his brother José lived, and where the celebrated Frasco el Colorao had a tavern before he settled in Triana for good, in the mid 1800s. When the cantaor from Triana said that Silverio was a disciple of Frasco, who introduced Silverio to his first cantes, he was correct, except that this didn’t happen in Triana but in Marchena. Colorao was the nephew of a guitar-maker, and we assume he played the guitar, and guitarists were the ones who would suggest which cantes were best suited for the younger cantaores.

Let’s not digress, though. Regardless of whom he learned from, the fact is that Silverio was the master of his time, the great flamenco personality who earned the respect and admiration of gypsies and not-gypsies alike, having a crucial role in the professionalization of flamenco. The year 2015 marks one hundred and fifty years since Silverio returned to Seville after his travels in South America. That’s an important anniversary because, even as flamenco was already being performed in cafés and theatres by professionals, such as Ramón Sartorio, José Lorente, José Perea, María Borrico, Enrique Prado and Juraco), it’s with the arrival of Silverio when cante really takes off, when flamenco starts to become its own genre, distinct from the earlier bolero, and when it gets out of the dance academies. Silverio created a flamenco company and started to tour the whole country, with so much success that he even saved the Andalusian theaters from a crisis. Flamencos drew bigger crowds than the actors and the tenors, and the press, always reluctant to report about this genre, understood that it had to pay attention to an art that was becoming established. Silverio had a lot to do with this process, without forgetting another vital personality from the Macarena district, Manuel Ojeda Rodríguez El Burrero, whom Seville has also forgotten miserably. For all the above, it’s baffling that the Andalusian capital hasn’t yet recognized Silverio as the most influential personality of the genre. I have written before about the need to create in his honor a flamenco archive center, something that, bizarrely, does not exist in Seville, especially considering the thousands of people who come to this city throughout the year to enjoy this art, including many scholars wanting to learn its history. Silverio is the history, the personality, the leading figure that allows us to comprehend an art that, thanks to him and to others like him, is now admired the world over. Why is this so hard to understand this?

Translated by P. Young