What ever became of tientos?

Who had the idea of relegating a form so full of possibilites to a mere opening act for tangos? Tientos, heavy, languid and claustrophobic.

Once upon a time there was a flamenco form known as “tientos”…well yes, it does continue to exist, so why do I have the feeling it’s getting away from us? It’s really tangos from Cádiz, but with a rhythmic lilt provided by the guitarist’s right hand which executes a kind of sexy tanguillo strum with a hiccup. Investigators tell us the clever invention can be attributed to Enrique el Mellizo (Cádiz 1848-1906).

Tientos was flamenco’s binary answer to soleá, measures divisible by 2 or 4 rather than 3. Once a jewel in the flamenco crown, tientos has become fast-food flamenco seldom heard except as a disposable introduction to tangos, resulting in tientos-tangos, and seldom danced on its own. A cante form on the express track toward obsolescence. Years ago, when I checked the database of the Centro Andaluz de Documentación del Flamenco, it showed 210 recordings of “tientos tangos”, and 1552 listed as “tientos”. Those figures are surely outdated, possibly even tied or reversed by now. The body is still warm, but the plug has been pulled, and it’s only a matter of time before tientos becomes a form in disuse.

I certainly defend the absolute autonomy of singers who must have their creative space, but letting tientos fall through the cracks only diminishes the repertoire. Imagine if soleá became absorbed as the introduction to some other cante… it’s unthinkable.

There are other similar situations of cantes becoming auxiliary bits to prepare ears and minds for the main cante. Livianas to preface serranas is a clear example, and no real harm done, since liviana is a relatively weak form that gracefully takes on the introductory role. Prefacing malagueña with granaína was a creation of Aurelio Sellés, but the respective forms have remained autonomous.

The music of tientos is more complex than that of the soleá/siguiriya branches of the flamenco family tree. Surprising harmonies and unexpected deviations make for rich musical variety without sacrificing communicative power. Camarón and Paco gave great dimension to festive styles such as tangos, feeding the boom of tientos-tangos.

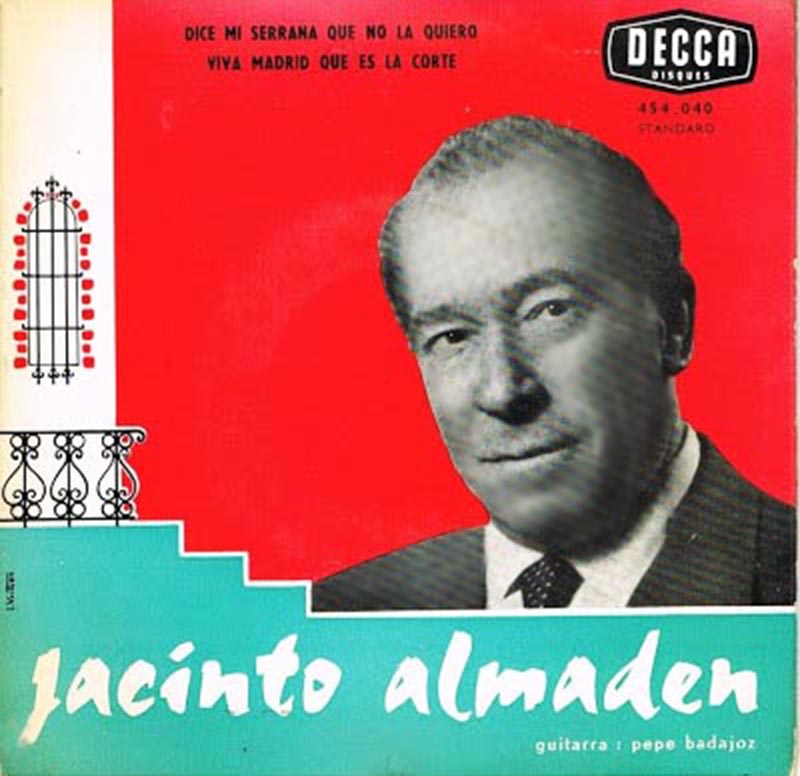

Looking back at historic singers, Pastora Pavón (1890-1969) found in tientos an acrid beauty that had escaped others. Jacinto Almadén (1899-1968), an underappreciated artist, delivered this form with a delicacy that was never saccharine. Caracol took easily to tientos with his big personality, and singers from Cádiz – Pericón, Manolo Vargas, La Perla, Chano and others – had a natural affinity for tientos that came of age as the tempo became more relaxed.

Gaspar de Utrera (1932-2008), the innocent bohemian, unlocked the potential of tientos, infusing the depth they promised. His concept of cante, always direct and honest, hermetic and highly personalized, went well with his plaintive voice to interpret this form. He squeezed out more flamenco angst from tientos than other singers manage to locate with siguiriyas, and his influence is detected in young singers when you hear two or three verses of his in a row: Los siete sabios de Grecia…, Presecito en la cárcel…, En la casa de la pena…, Agua fresca quien la bebe…, Al escucharlo temblé… among others he regularly interpreted.

In Jerez, the serious intensity of Manuel Agujetas (1939-2015) caused him to reject even the slightest hint of a frivolous ending for tientos. Terremoto de Jerez (1934-1981) would usually tack on a very brief tango closure, and from this same generation of maestros, was Antonio Núñez el Chocolate (1930-2005) who would add a short tango verse to close out his tientos.

José Menese (La Puebla de Cazalla, 1942-2016), with the verses of Francisco Moreno Galván, such as the famous Señó que va a caballo, y no daba los buenos días, si el caballo cojeara, otro gallo cantaría, was among the last singers to respect the integrity of tientos as a song form in its own right. He hunted down the duende, and rarely (never?) used the form as a prelude to tangos.

Miguel Poveda has, on occasion, sung tientos in the traditional manner, with only a brief tango bit at the end. And today’s veteran maestros, Fosforito, María Vargas and Pansequito among others, have recorded tientos with only the traditional short tango ending, although on other recordings they have also been open to a longer excursion into tangos. Generally speaking, the older the singer, the less likely they are to end tientos with anything more than a short snippet of tangos.

Who had the idea of relegating a form so full of possibilites to a mere opening act for tangos? Verses and melodies are shared easily by both forms, but with different feeling and intent. Tientos, heavy, languid and claustrophobic. Tangos, with a canastero feel, catchy melodies from Granada and Extremadura, or the occasional pop song that sneaks in when no one is looking.