Plain Pansequito

Naturally, for chronological reasons, I didn’t have the privilege to witness the release of tons of albums

By Paco Canela

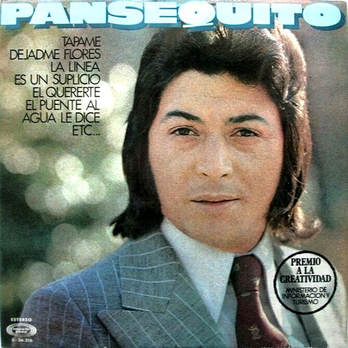

Naturally, for chronological reasons, I didn’t have the privilege to witness the release of tons of albums, but many of these recordings have defined my life as a flamenco aficionado. One of those albums with a special place in my heart was recorded by José Cortés Jiménez, better known in the flamenco world by his stage name Pansequito, his family nickname, or also Pansequito del Puerto, because even as José was born in La Línea de la Concepción in 1946, he lived since an early age in El Puerto de Santa María, and it’s very common in the flamenco world to add the artist’s hometown to his stage name. That album, pictured here, was published in 1974 under the record label Movieplay (S-26.216), and it also featured the guitars of Juan and Pepe Habichuela (born in Granada, in 1932 and 1944 respectively).

This was Pansequito’s forth album, released after he took part in the seventh edition of the Concurso Nacional de Arte Flamenco de Córdoba (year 1974), where this artist was awarded a prize specifically created for this occasion: the Ministry of Information and Tourism’s Creativity Prize (Premio a la Creatividad del Ministerio de Información y Turismo), because the singing style of Pansequito didn’t fit at all within the standards of this contest in Córdoba. As we can see in the album’s image, this prize was publicized in the sleeve. Oddly, it was never awarded to any other artist, thus Pansequito is its sole recipient, something that speaks volumes. When we listen to this album, we realize right away what was the reason that prompted the jury in this contest of Córdoba to award Pansequito such unique prize: the creative personality of this artist from La Línea and El Puerto.

The first track of the album is his number one hit: Tápame, widely known bulerías which, together with the other two bulerías in this album, Mi niño and ¡Ay, qué mora!, show Pansequito’s mastery in this palo, where he is absolutely outstanding, having an overwhelming rhythm, with unique forms and turns that have led aficionados to call such style Bulerías de Pansequito, since they’re his own creation. The guitars of the Habichuelas are impeccable, with these two brothers of Granada showing the maximum concentration and taking the cantaor in their wings all along. The soleá Dejadme flores, a solo with the guitar of Pepe Habichuela, is a monument. Yes, a monument. The first verse, Al paño fino en la tienda, in the style of Alcalá, made famous in the voice of Manolito de María, is performed by Pansequito in his own way, but it’s the second verse Y corta, es que la vía era mu corta which blows our minds away. What a way to link the tercios! What a superb breathing control! It doesn’t matter how many years have passed, even after listening to this soleá one thousand times, it still blows or minds away. José then continues with Es un suplicio el quererte, por tientos, the most conservative track in the album. The commercial bent is added in the following track, El cristal cuando se empaña, a fresh rumba which was also performed in those days by the band Los Chichos. By including this rumba in the album, Pansequito perhaps wanted to make a splash like Paco de Lucía did the year before with his rumba Entre dos aguas. The album continues with the fandangos La Línea, this time just accompanied by the guitar of Juan Habichuela. In these fandangos, Pansequito sings to his people, once again showing off his powerful lungs, singing it all in almost one breath. The last two tracks of this album are the alegrías No sé si debo quedarme, another style of cante that is unique to this cantaor, and the tangos El puente al agua le dice, both accompanied by the outstanding guitars of Juan and Pepe Habichuela, the universal artists from Granada.

Nine tracks in total, where Pansequito renews and creates without any cheap or weird tricks, something which sadly is very common these days. It’s been more than forty years since this album was released, and at that time Pansequito was a revolutionary. Today, he’s a classic. His love for his art and his perseverance made this miracle happen.

Translate by P. Young