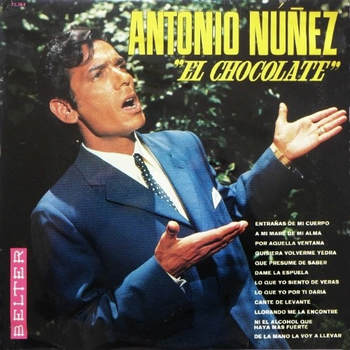

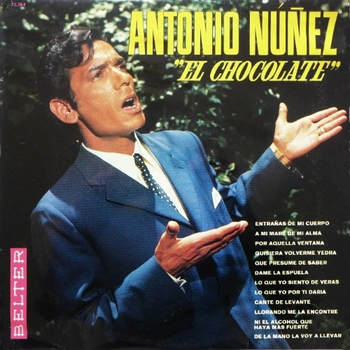

El Chocolate, “Entrañas de mi cuerpo”

These days, releasing music albums with specific titles seems completely normal.

These days, releasing music albums with specific titles seems completely normal. However, this wasn’t always the norm: discography experts used to refer to any given album by its record label and catalog number. A good example of this is the LP in today’s article, which has no title and was released by the Belter record label with the catalogue number 22.284, so it’s would be known as Belter (22.284). However, to avoid technicalities, aficionados often refer to such albums by the name of its first track, and that’s what I’ve done here.

“Entrañas de mi cuerpo” is the first LP of Antonio Núñez Montoya El Chocolate (b. Jerez de la Frontera, 1930 – d. Seville, 2005). Previously, Antonio had recorded a series of wonderful EPs, the first one in 1963, accompanied by the guitars of Paco Aguilera and Félix de Utrera, another six EPs accompanied by Melchor de Marchena in the years 1964 and 1965, and six more EPs accompanied by Niño Ricardo in the years 1966 y 1967, definitely recommended. Thus, we get to 1968, when Chocolate brings us another sublime record, the album we’re featuring in this article. In this occasion, the cantaor performed with the guitars of Manolo de Brenes and Antonio de Sanlúcar, which perfectly wrap Antonio’s deep cante throughout ten tracks.

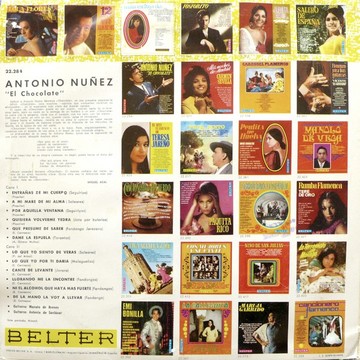

On the album’s back cover, there is a short text written by the late flamenco critic Miguel Acal:

“Defining Antonio Núñez Montoya ‘Chocolate’ is very difficult. In our opinion (shared by a multitude of aficionados), Chocolate is the best example of the ‘duende cantaor’. Chocolate’s cante may no be precise, measured to the millionth part, but his cante reveals a man devoted to an art. Chocolate doesn’t sing with his throat, he sings with his heart, with his eyes, with his hands… His whole being sings, not just his voice. Gypsy to the bone, he mixes in his soul the grace of having been born in Jerez and the duende of having grown up in Seville’s Alameda de Hércules during cante’s golden age. Chocolate has come from afar, and he’ll go far. He passed by, with anguish, touching us with a sorrowful duende or a joyful angel. The depth of Antonio Núñez ‘s sorrow is perhaps the expression of Gypsy sorrow, suppressed for many years. Yet, the intensity of his singing’s joy, his angel, can erase the pain of betrayal. Chocolate spills out sugar. The mystery of cante’s duende takes hold of his soul, shaking it. This is perhaps the most perfect definition of Antonio Núñez. Genius: that’s what Chocolate is”.

It’s not a bad description of Chocolate, although we shall recall what this cantaor said many years later: “Duende doesn’t just show up. It must be sought.”

This album has a double ration of seguiriyas: “Entrañas de mi cuerpo” and “Por aquella ventana”, accompanied by the guitars of Manolo de Brenes and Antonio de Sanlúcar, respectively. In my opinion, Chocolate is one of the best performers of seguiriyas of the last sixty years, with his voice so full of energy, so flamenca and with such perfect vocalization. Like we say in flamenco, a “monster” (as in “all -powerful giant”), without a doubt. Chocolate avoids the excessively long notes which other artists use to perform the so-called cantes grandes. He has no room for monotony, and his cantes are startling, unsettling the listener at every verse.

The same can be said about Chocolate por soleares. His way of linking the verses “a lo Tomás” is truly exceptional. Chocolate always stated categorically the Pavón siblings were the artists who influenced him the most, particularly Tomás, something which stands out when we listen to the soleares in this LP which, by the way, are also a “double ration”: “A la mare de mi alma” and “Lo que yo siento de veras”, both accompanied by the guitar of Manolo de Brenes.

Attempting to dissect the different styles in flamenco is like going into a lion’s den. We may find similitudes among cantaores who recorded their cantes, but attempting to go beyond this may cause us to fall into an endless abyss, because the numerous labels applied to cantes turn the flamenco landscape into dreadful gibberish: was the seguiriya of Manuel Torres a version of the seguiriya of Manuel Molina or Francisco la Perla? Was Frasquito’s fandango a verdial de Vélez, popularized by Juan Breva? Was the soleá of Juanichi El Manijero in fact created by Frijones…? It’s all a non-ending labyrinth of names. There are styles which are so similar that it’s hard to believe that they were created by so many different people. That reminds me of the words that my friend Gregorio Valderrama uttered one day, during a good flamenco discussion: “Those attributions bite me like wasps!”. Not quite, he forgot to add spiders, centipedes, scorpions and all sort of poisonous critters.

We now travel to northern Spain to enjoy a jota navarrica, “Quisiera volverme yedra”, which Chocolate performs a compás de bulería. Including other musical styles in flamenco is something that many other cantaores have done throughout history. For example, Fosforito performed rancheras, Antonio El Chaqueta performed boleros and Chano Lobato performed Argentinian tangos. Chocolate had a natural voice which enabled him to sing all kinds of music. Who remembers Chocolate singing the Spanish version of Matt Monron’s “Born Free” in the famous TV series “Rito y geografía del cante”? Phenomenal!

We continue with a style where Chocolate excels: fandango. This album includes six different fandangos in four tracks: “Que presume de saber”, “Llorando me la encontré”, “Ni el alcohol que haya más fuerte” and “De la mano la voy a llevar”, all of them very well known by flamenco aficionados. Antonio Núñez grew up in Seville at the time when it had great fandango performers, such as El Pinto, Caracol, Vallejo, El Gloria and El Sevillano, and he ended up creating his own type of fandango, with which he enthralled audiences throughout his long career.

“Dame la espuela” is the Taranto with which Chocolate and Manolo de Brenes delight us in this album. That same year, this cantaor recorded another Taranto: “¡Ay! mi muchacho”, featured in the EP Belter (52.215), which probably was not included in this album for lack of space. Both of these tarantos were performed under the shadow of the genius of Jerez, Manuel Torres.

Then we have “Lo que yo por ti daría”, a rare performance of the malagueña del Mellizo, as Chocolate finishes it with an abandolao. It’s rather unusual among cantaores to finish this type of malagueña with an abandolao, and it’s even frowned upon by some. Yet, anarchy rules everywhere with Antonio Núñez Montoya’s cante.

With the exception of the jota por bulería cited above, we can say that all cantes mentioned up to now were part of Chocolate’s usual repertoire, although we must add the cantes de fragua, which Chocolate performed superbly. However, artists are prone to explore other “terrains”, and sometimes end up recording styles beyond their comfort zone, perhaps attempting to be acknowledged as having that sought-after encyclopedic flamenco expertise. As an example, we have “Cante de Levante”, jaberas, a style which Chocolate performs as if fulfilling a duty.

Overall, Entrañas de mi cuerpo is an album which every good flamenco aficionado should have in their collection, as it showcases what, in my opinion, was the best of times in the career of an artist whose name is already etched in gold in flamenco history. Among other important accolades, he was awarded the Medal of Andalusia and the Grammy Latino, even as he used to say: “In order to sing well, I have to like my public.”

¡QUÉ GRANDE, CHOCOLATE!