What does it mean to be a cantaor?

Like a bullfighter watching the bullfight from the stands. A cantaor who goes off key when rushed, yet sings from the heart. What does it mean to be a cantaor? It means singing with the memory of our soul.

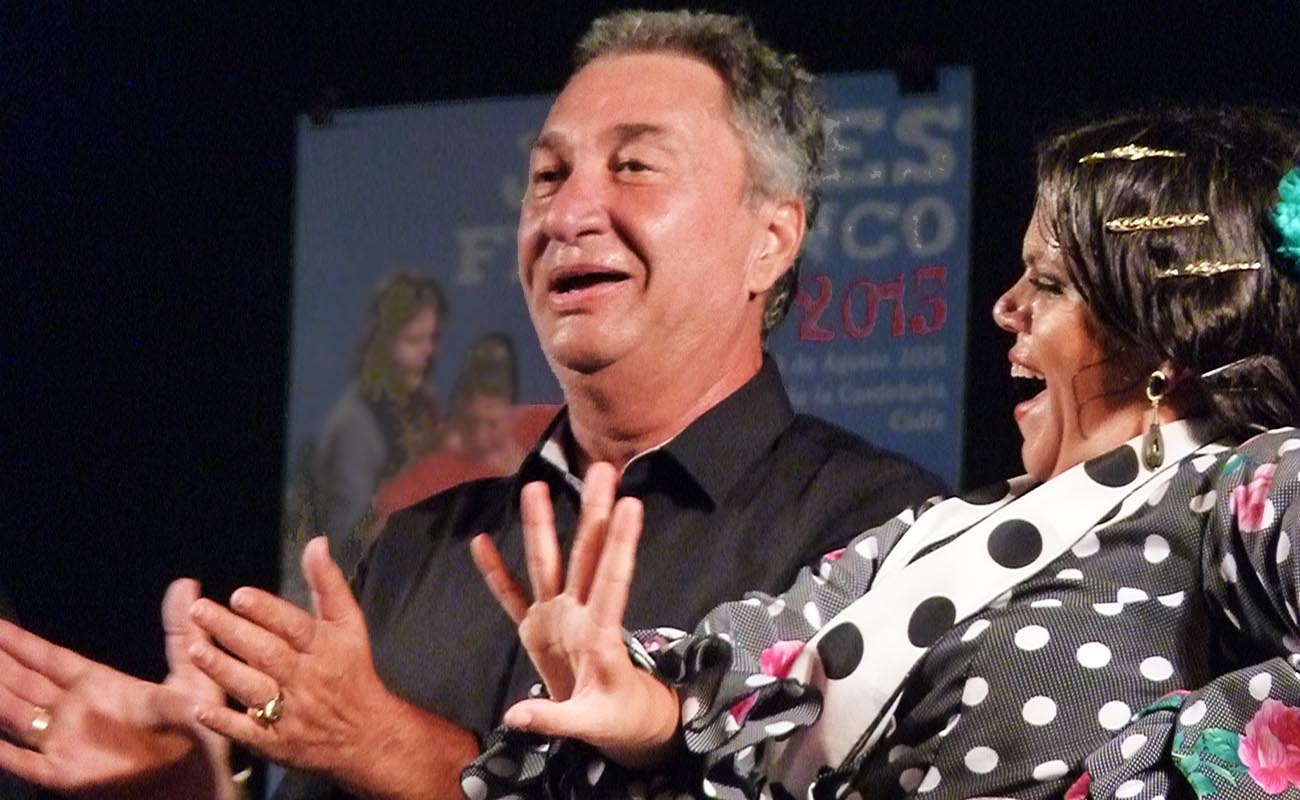

A good blog writer should never write about himself, but only about those whom the readers care about. However, today I need to write about myself, to tell something that I have sometimes pointed out and that many people already know. I am a failed cantaor. Failed, but a cantaor, nonetheless. As the great Manuel Centeno once said, tired of the dictatorship of pellizco: “I am a good cantaor, but I don’t have a nice voice, I don’t have a powerful voice, and I have no duende”. I know a thing or two about cante, but who cares about this? Who cares about jondo wisdom? In the old times, knowledge was something truly appreciated, but these days what really matters is the façade, the wardrobe, the stage, the graceful footwork, the Facebook pic.

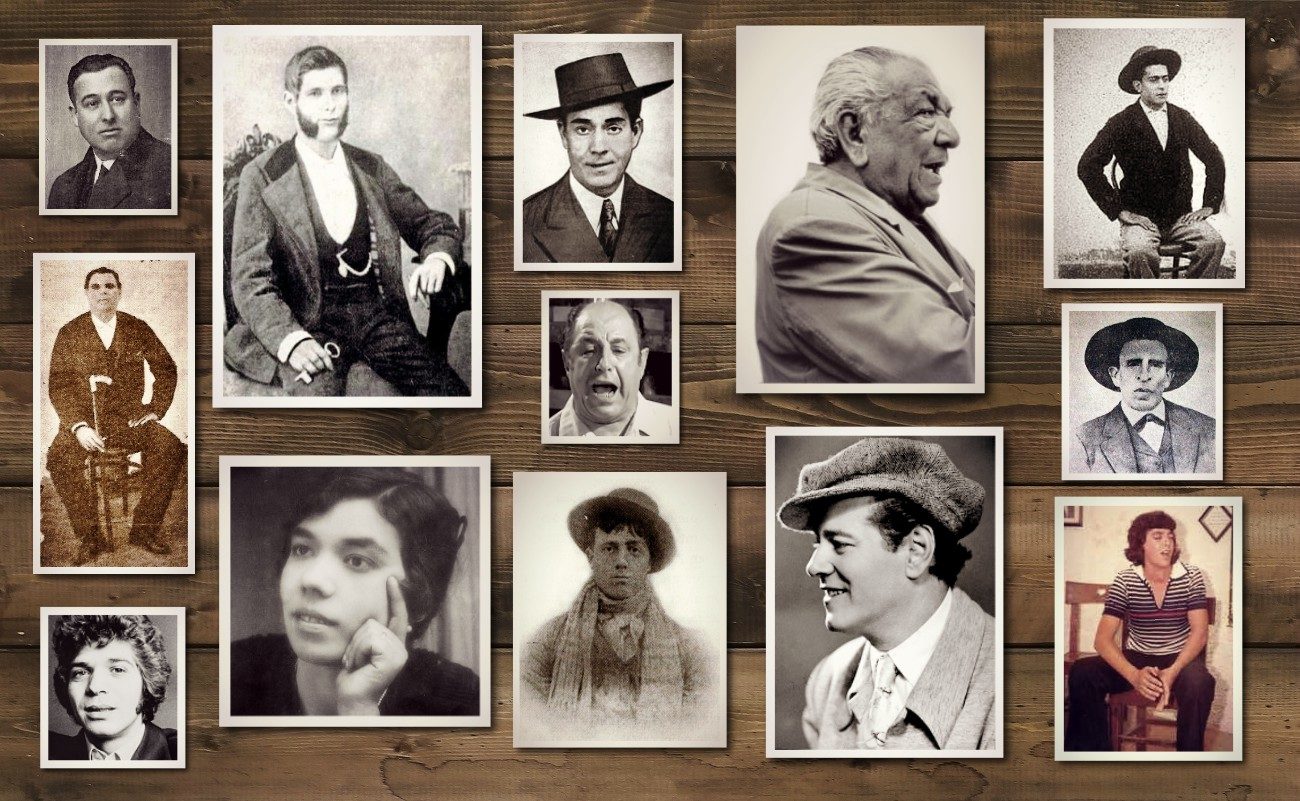

I was born in the wrong century. I’m more 1800s, like Nitri or Frijones or Ramón el Ollero. Tomás Pavón used to sing for the fishes (barbels, specifically); I sing for the olive trees. El Mellizo used to go to churches in Cádiz to cool down and to listen to the priests singing; I lock myself in my den with the lights off, knocking my knuckles on the desk, marcando compás, remembering those who sang because they needed to express their emotions.

In my room, there is a plaster bust of Camarón wearing Marchena’s flat cap, and a photograph of Pepe Torres that his daughter Tomasa had at her home. There are hundreds of books, yellowish due to age and nicotine. Old anthologies. The knife that (possibly) immortalized El Canario. A scarf that belonged to Farruco. Two of Mario Maya’s dance outfits. Manuscripts by Ricardo Molina and letters of Mairena. Two little combs which belonged to Niña de los Peines. Vallejo’s dance boots. A piece of a cross that Joselito El Gallo bought for his mother, Gabriela Ortega Feria, when she died. Old sepia-coloured photographs, zealously kept in a box of La Estepeña biscuits. A record by Tomás Pavón, the one with Rieniego, which Pastora and Pinto used to hug when they missed him (which was almost every day). Marchena’s Italian hand-made shoes. One original photograph of Juan Talega by Benito Moreno. A painting by Manolo Sanlúcar (“El Partenón”), varnished with triple time signature in the Doric style. A voice mail from Félix Grande telling me he felt moved by a story about my grandfather. Some tapes where Ramón Medrano, cantaor from Sanlúcar, talks about the giliana and the Mirris cantes (the “small one” and the “big one”), among a hundred other things.

To be a cantaor is also to love the things of those who passed away. A frustrated cantaor, yes. Tormented and powerless against a tercio seguireyo of the Marruros (an awfully difficult creation of those dirty-poor gypsies of Jerez who sang in the tabancos and tenement courtyards of Santiago or San Miguel). Cantaor with a charmless and graceless voice, with no gift for art or beauty, yet a cantaor nonetheless. Author of lyrics, of verses from my soul. Researcher of data in cemeteries, parishes and tribunals. Dreamer of impossible parties, of chimerical mano-a-manos and flamenco binges that are only real in my imagination. Cantaor, for sure. Full of shame, shy, of those who close their eyes, so we don’t see those who don’t know we close them to look inside us, deep where there’s a fusion of sensibility, pain, jealousy, passion, love, bitterness, fortune and misfortune, the taste of wine, the scent of roses and jasmines in dented flower beds of old yards. Cantaor, sure. Old fashioned if you wish, but cantaor. Like a bullfighter watching the bullfight from the stands. A cantaor who goes off key when rushed, yet sings from the heart. What does it mean to be a cantaor? It means singing with the memory of our soul.

Translated by P. Young