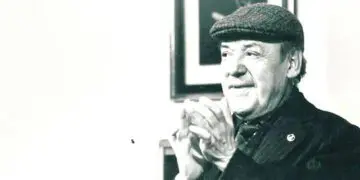

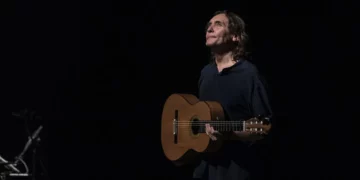

Paco de Lucía and Manolo Sanlúcar were scheduled to have a concert in the Canary Islands and they decided to prepare for this concert in the north, in a cottage where they took their respective wives. They would wake up, have breakfast, go for a walk in the woods and work on the concert preparation until lunchtime. At night, exhausted, with their fingers hurting, they would have dinner and drink a little, talking about flamenco, joking around and relaxing. It was always Manolo who would finally say that it was time to unwind and get some sleep, so they could continue working the next morning.

Manolo once told me that in one of those nights, already in bed with his wife Ana, they would listen how Paco, in the adjoining room, would review all they had worked on during the day, without a break, until dawn. “He beat me on that one, with his capacity to work until he had no strength left”, he told me at his farmhouse in El Pedroso, while he cooked some eggs and chorizo. “He was tireless”, he added. On top of his incredible natural talent, which allowed him to create extraordinary musical compositions, revealing his superb skill as a composer, Paco was able to revolutionize flamenco based on his incredible, colossal abilities never before seen in the history of flamenco or of Spanish guitar.

As we praise Paco’s talent and natural genius, we must not lose sight of his strength and stamina, of his rare ability to wear down everyone else. It is a pity that the media seldom mentions this aspect, while referring to Paco as if he almost were a God, which is not true. Paco was made of flesh and bones, a humble artist gifted for music like no one else. Manolo was different, a tormented great musician who would have broken all of his records if he could. He was prouder of his teaching and research achievements than of his compositions. Yet, he left us, among his many otherworldly jewels, the best album in the history of flamenco guitar, Tauromagia. Hats off, please!

«Let us not turn him into a magician who leaves everyone spellbound when taking a rabbit out of his hat, because he was in fact a boy from Algeciras, from a poor family, shy, with his own issues, who had to work much harder than everyone else»

It bothers me that Paco de Lucia is often treated as if he were a God, because that does not give him due credit. God is kind of a magician who created the whole world in six days, with every detail, and it all turned out very pretty. Then we humans came and messed up everything. Just today I read in a Spanish newspaper something about Paco, “from the handouts of the rich to the Real Theater”, suggesting that before Paco all flamenco artists were basically beggars. That is not true. Silverio and Juan Breva were hot tickets who would perform to full theaters more than a century ago. And the same goes for Antonio Chacón and Niña de los Peines.

Julián Arcas, Paco el Barbero, Paco el de Lucena, Ramón Montoya, Sabicas and Niño Ricardo had already dignified the flamenco guitar much before Paco’s father, don Antonio Sánchez Pecino, had been born. We must not regard Paco de Lucía as a God, but as an extremely talented man who worked harder than anyone else, almost like a slave, to give us his unparalleled music. Let us not turn him into a magician who leaves everyone spellbound when taking a rabbit out of his hat, because he was in fact a boy from Algeciras, from a poor family, shy, with his own issues, who had to work much harder than everyone else, so much so that nowadays he is almost considered a God.

Traslated by Paul Young