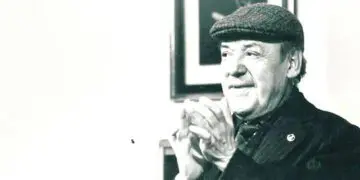

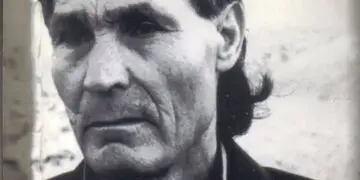

In the month of April 1973, a new piece of music began to circulate. It soon became popular in Europe, the Western world, and beyond. Entre dos Aguas it was called, and not even Paco de Lucía could understand the impact of that rumba of his that opened the gates to a new flamenco era, and an unstoppable revolution that continues to follow its path 50 years later. The international audience keeps growing, most of Paco’s followers hadn’t even been born when Entre dos aguas was playing on every radio station in the country, at all the fairs… That instrumental piece, not by any means the best of Paco, captivated us all and opened a new chapter in the genre.

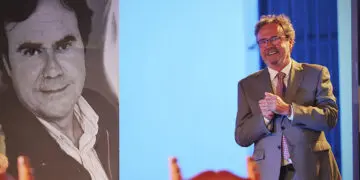

On March 7, 2024, the Foundation for Iberian Music at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, in collaboration with the Flamenco Festival New York City, will present an international symposium dedicated to exploring the indelible influence of the Americas on Paco de Lucía and, in turn, his impact on Hispanic music and performers. The participation of Rafael Riqueni has been confirmed, among other musicians and scholars such as John Moore and Peter Manuel, whose book Flamenco Music: History, Forms, Culture has recently been published. Publication of the symposium proceedings in an anthology is planned.

The title of the iconic piece Entre dos Aguas has long been a subject of debate. However, I recall a radio interview with Paco in the summer of 1974 where he was asked about its meaning. He explained that it referred to the cultural blending represented by the meeting of the waters of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, which converge in Algeciras, the birthplace of our genius Lucía.

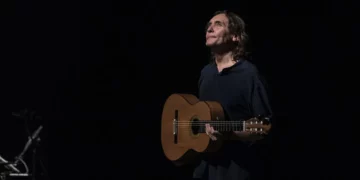

Paco often spoke of his commitment to aiding the birth of new flamenco forms: «The guitar is changing, and I have an obligation to the people who follow me, to open up new territories. Flamenco must be allowed to sound the same, but with a new vocabulary.”

And he has certainly fulfilled that commitment. Which is the reason we’re discussing his enormous contribution. In the 20th century, the importance of Arab culture in flamenco was considered a given. Now, for a few decades, importance has been attributed to the derived Hispanic, Latin American, Caribbean, etc. cultures. That’s how what we now call fusion or world music emerged, a blend of new flavors giving birth to sensations with their own identity.

What follows is a brief interview with K. Meira Goldberg from the Foundation for Iberian Music, which is organizing the symposium:

Meira, does the average American know who Paco de Lucía was?

Unfortunately, I highly doubt that the average person in the U.S. knows who Paco, or Carlos Montoya, or Carmen Amaya, or Lola Flores, or Sabicas was. But perhaps if there’s one on this list, it’s Paco.

Do you think Paco’s fame has enhanced flamenco appreciation in the United States?

Absolutely! Very much so.

Does the typical non-Spaniard prefer flamenco dance to singing or guitar?

The typical non-Spaniard doesn’t really know what to make of the singing, and doesn’t like the sound of it. But I think flamenco in general is getting more popular in the States, and that means especially both dance and guitar.

Will the city’s Hispanic population attend the Festival and symposium?

I think some Hispanic people will attend the Festival, of course, but its main audience is flamencos and New York’s general theater-going population. Our symposium is free and open to the public, and I think it will draw mainly flamenco followers, as well as musicologists and ethnomusicologists.

There used to be a good number of flamenco dance schools in New York City. Has that changed?

After Fazil’s rehearsal studio closed in 2008, flamencos scattered throughout the city. Flamenco Vivo‘s classes and studios in Times Square are thriving. Sonia Olla and Ismael Fernández have opened up their own studios in the same building. Xianix Barrera has a space in East Harlem and has many students. Jorge Navarro has studios downtown, and Soledad Barrios has a space on the Upper West Side. Post-Covid there are a bunch of online classes: Alfonso Cid teaches singing, and Guillé Guillen has a marvelous site covering all the basics.

How long has this symposium been in the planning? Does the project receive support from the New York City municipal government?

We’ve been planning this symposium for a couple of months now. We’re still finalizing the program, but we’re thrilled to have the participation of several prominent scholars and also the maestro Rafael Riqueni. We also hope to bring in the voices of several people who knew Paco: Pedrito Cortés, René Heredia, and perhaps you Estela could record a short reminiscence on video?

The event is supported by the Flamenco Festival and by the Foundation for Iberian Music at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York.