What’s in a name? Attributions and labels in flamenco

Newcomers to flamenco are often baffled by the variety of forms or “palos”, and the many variations within certain forms.

This is slippery territory, there are flamenco forms that are locked into one or two specific styles, but the most basic and potentially expressive forms have literally dozens of distinguishable variations, such as occurs in particular with soleares (soleá) and siguiriyas. How did we end up, for example, with only one type of caña (historically there were more which became obsolete), yet we have soleares that are literally too numerous to mention, as many as 70 according to experts.

I was recently asked about cante labeling, but who knows how it took place, other than to say that such things are probably subject to trends, and the weight of public opinion has the final decision. Two popular singers, Camarón de la Isla and Juan Peña el Lebrijano, took a crack at adding new forms to the traditional repertoire, but their creations, respectively dubbed Canastera and Galeras, though remembered, have not won the enduring popularity either singer had hoped for.

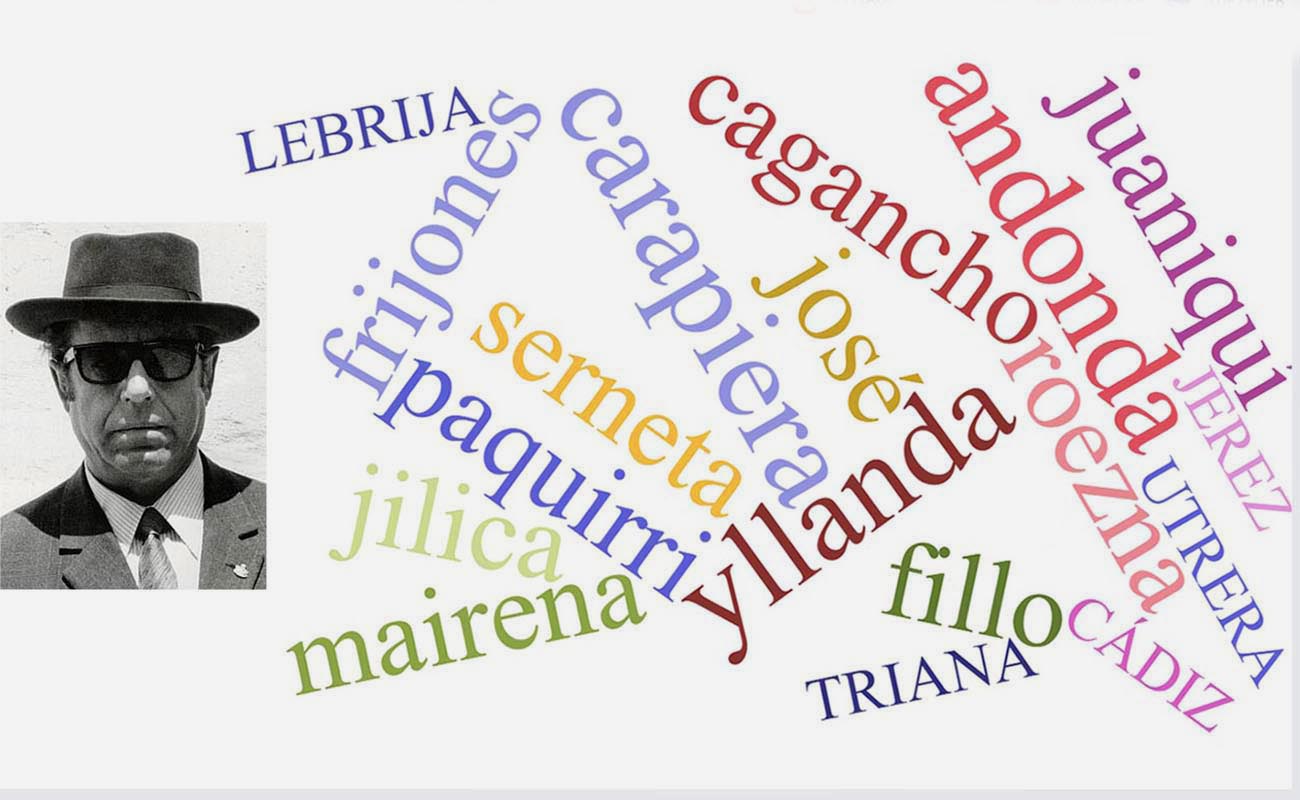

It could be argued that the form soleá is the most musically complete and sophisticated member of the flamenco repertoire. This jewel in the flamenco crown has to bear the indignity of endless “styles”, clearly distinguishable from one another and known as “soleá de…“. Attributions may be to individuals, such as soleá de Frijones, to places, such as soleá de Alcalá or even the nature of the music, such as soleá apolá.

Instead of soleá de Serneta or soleá de Alcalá, those same classic forms might just as well have been labeled as song groups in their own right. Conversely, I wonder who decided the polo, which is just a click away from the form we know as caña, was deserving of a name of its own. Why was it not called caña chica or something similar indicating the connection?

The lighter forms tend not to repeat the soleá type of attribution. For example, the form we all know as caracoles might, in another era, have been called cantiña madrileña, but actually we ended up with a string of cantes in the same basic classification of cantiña, each of which received its very own label. In addition to caracoles, we have romeras, mirabrás, cantes del Pinini and alegrías de Córdoba among others.

Another question is, why has it become so fashionable to identify cante forms, especially when most attributions can’t be confirmed, or enjoy limited consensus, and end up as mere labels to distinguish the styles despite possibly dubious historical accuracy? It was singer Antonio Mairena who made us all snap to attention and study the many variations, occasionally (we’re told), slipping in some creations of his own that he passed off as those of historic singers.

As recently as the 1950s, even avid flamenco fans had little or no interest in the labeling of styles. Consider this: in the Ducretet Thomson anthology of 1954, the first anthology of flamenco singing (released in Spain by Hispavox in 1958), guitarist Perico el del Lunar, who was in charge of the project, clearly had the objective of documenting every flamenco song-form, including those in disuse, such as trilla or marianas. However he only saw the need for one example of soleá, which happened to be from Triana in the voice of Pepe el de la Matrona, thus ignoring the rich diversity of soleá styles from the rest of the relevant area of western Andalusia. In an interview, Morón guitarist Manuel Morilla, born in 1924, commented that in his youth, the average flamenco follower knew nothing of “exotic” song-forms such as debla, caña or serranas.

Let’s give the last word to a well-known investigator of these issues, the late singer José Sánchez Bernal, “Naranjito de Triana” (Seville 1933-2002), regarding the tangle of styles and attributions, as reported by his daughter, Pepa Sánchez Garrido. Naranjito happens to be referring to soleá de Triana, but the process he describes could be applied to any flamenco song-form:

* The soleá of El Sordillo, it’s not that it was a complete creation of his own, but he did give his own interpretation, something that people were able to identify: “That’s how El Sordillo sings it”. And after much repetition, people just said “la soleá de El Sordillo”. Cantes y Cantaores de Triana [p.58].