The Legacy of Antonio Gades Remains

Gades left us on July 20th, 2004, and the candles of his vigil have burned out. But all together we celebrate him, because everything good is like the fire, which cannot be hidden from sight. Twenty years later, the legacy of Antonio Gades remains.

In the 1990s, yours truly was already known for many years a the “hammer of flamenco heretics”, an epithet bestowed upon me by my good friend Francisco Vallecillo Pecino, making true the maxim of the master Manuel Alcántara, when he said that journalism cannot be objective, because journalists are subjects, sometimes subjects to be wary of.

The nickname soon spread like a sound wave, with unfavorable consequences, to the point that I was forced to give quite a few explanations. Among those, I fondly remember one given to Antonio Gades in Seville, at the time of the Spanish premiere of Fuenteovejuna, a wonderful production which closed the trilogy by Zorrilla (Don Juan, 1965), García Lorca (Bodas de sangre, 1974) and now Lope de Vega.

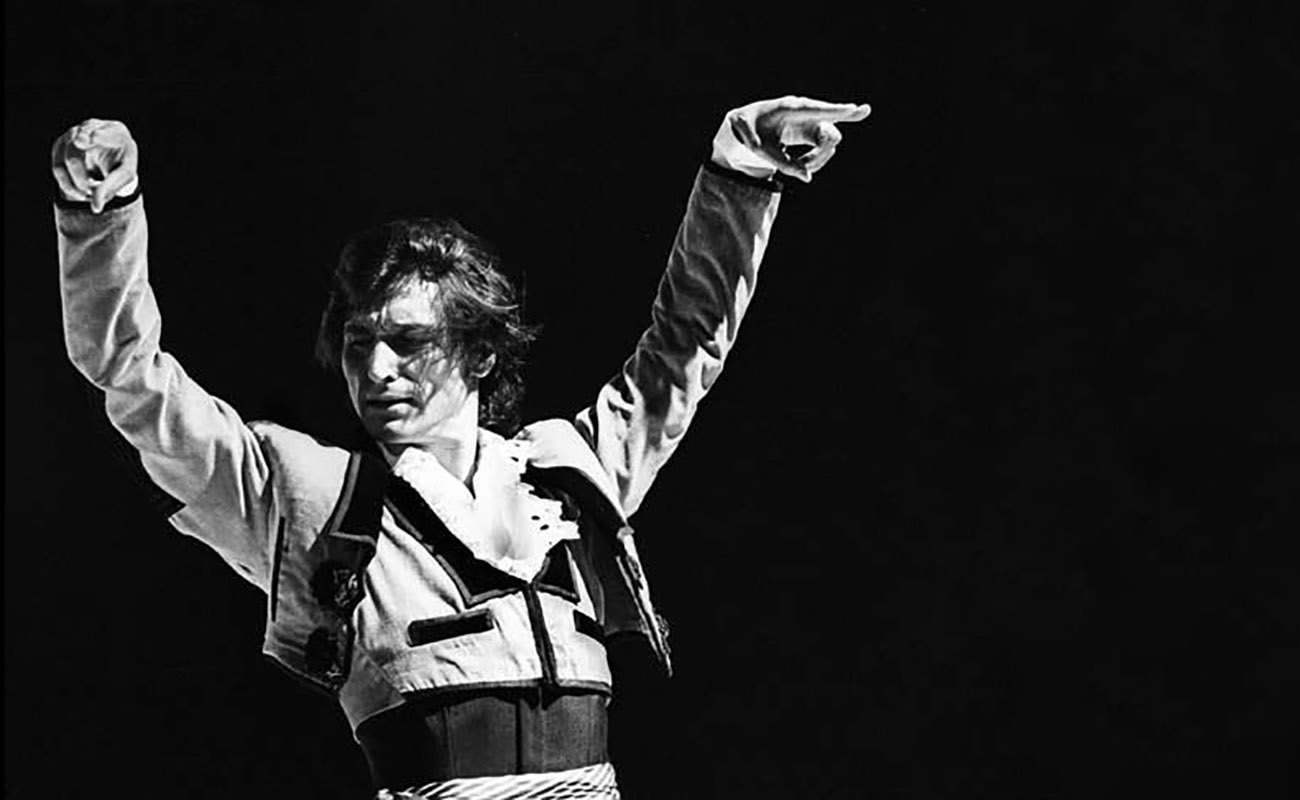

That evening Gades had achieved a veritable apotheosis at the Maestranza Theater. The public filling the venue, all together, rewarded him for several minutes with palmas por bulerías, without a doubt thankful for that new and decisive accomplishment in the field of Spanish theater dance, topped with the utmost neatness by this great maestro from Elda (Alicante) with the basics of our rich folk tradition.

As I discussed that outstanding performance with my colleague Miguel Acal, we were joined by Enrique Pantoja and Manolo Sevilla, who told me that Gades wanted to see me. I could not figure out at that moment which of my critics might have upset him. I was quite surprised, then, that the reason for that “laborer of culture” (he did not like when I addressed him as “maestro”) wanting to see me was to ask me to highlight the work of Paco Vallecillo, giving it even more consistency, as long as I always «stood up for dance as an artistic expression, but above all as Culture», because he was against going beyond «the limits of what is permissible».

I took this way of appreciating the value of what belongs to culture, protecting it in the same way as his maestra Pilar López and his contemporary Mario Maya did, as the forging of a cemented identity, so necessary in the baile flamenco of that time, which Antonio Gades preserved through socialization as the source of social cohesion. That is why I think is important to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his death.

That day, July 20th, in the evening, we came across a conclusive definition by his partner, the maestra and friend Cristina Hoyos: «Antonio marked an era, but if we are talking about innovation, professionalism, theater and choreography, then Gades is the one who took the highest leap this century».

Gades became a dancer «to stave off hunger». As soon as Pilar López saw him performing on stage, she not only made him part of her company, but, in his words, educated him «as a dancer and as a person», teaching him that «the important thing in dance is not to be better than the others, but to be better than yourself », as he told me in that premiere of Fuenteovejuna in Seville. She even came up with his stage name: Antonio Gades was born. Yet, before climbing through various positions in the company, he enriched his body with the wise teachings of other maestros, be it Lorca’s bolera school, El Estampío‘s footwork, El Gato‘s farruca or Pedro Azorín‘s jota aragonesa.

It is then when, already being the lead dancer in the company, he came across the works of Federico García Lorca, and he chose to focus on flamenco. In his nine years with Pilar, Lorca’s inspiration solidified, until 1961, when he quit Pilar López company, premiering one year later as choreographer in Rome and Spoleto, starring Lorca’s El retablo de don Cristóbal, and later staging Falla’s El amor brujo at Mila’s Scala theater

«In 1971 Spain was enthralled by El amor brujo, production that earned high acclaim by public and critics alike all over the world. In 1973 he toured Cuba, a country with which Gades had had a close relationship for many years»

From Italy he went to Paris, where he got in touch with French artists and intellectuals. Later he returned to Spain, to setup his first company, debuting in Barcelona, where his trademark and lifelong austere expressive style was already apparent.

One year later, in 1962, he was casted in the role of Mojigondo in Los tarantos, a film by Francisco Rovira Beleta where he performed together with Carmen Amaya. In 1964 he was awarded the Gold Medal of Touristic Merit, which established Gades as a bailaor who would make history performing his indisputable mastery in complex styles such as the seguiriya or the farruca, gaining innumerable followers along the way.

It was in 1965 when Gades premiered in Madrid his celebrated Don Juan, with screenplay by Alfredo Mañas, music by Antón García Abril and stage set by Viola. As Granero would say, this production «tightened up Spanish dance». Due to the texts by Machado, Neruda and Alberti, it faced censorship by Manuel Fraga Iribarne, Minister of Interior at the time, what explains why it was «taken down the day of its premiere», like Gades put it.

Political persecution forced him to work in the tablaos of Madrid until he went on a tour of Latin America, returning to Spain in 1967 to film a version of El amor brujo, by Rovira Beleta, as well as other movies, work he complemented with choreography commissions and the presentation of his company in Paris, where on April 21st, 1969, he introduced Cristina Hoyos at the Odeon Theater.

Yet, in 1971 Spain was enthralled by El amor brujo, production that earned high acclaim by public and critics alike all over the world. In 1973 he toured Cuba, a country with which Gades had had a close relationship for many years, increasing his support for the Cuban regime and taking active and public participation against the American embargo.

At any event, Bodas de Sangre, his first masterpiece, premiered in 1974. One year later, Gades retired from dance, in protest against the death sentence of five colleagues who opposed Franco’s dictatorship. Yet, in 1978 Gades was chosen as the first director of the Ballet Nacional Español (BNE), a position he kept until March 3rd, 1980, when the short-lived Minister of Culture, Ricardo de la Cierva, replaced him for political reasons with Antonio (Ruiz Soler).

The changes at the BNE allowed some of its members, led by Antonio Gades, Cristina Hoyos and El Güito, to create the cooperative Grupo Independiente de Artistas de la Danza (GIAD), which toured all over the world until its disbandment. Gades then started taking part in a series of musical films by Carlos Saura: Bodas de sangre (1981), Carmen (1983) and El amor brujo (1985), a trilogy where, according to Saura, «Gades achieved what I thought was impossible, preserving the popular in the deepest sense».

Then Gades would premier Fuego in Paris (1989) and Fuenteovejuna1 in Genoa’s Opera (1994), a colossal production performed in Spain in 1995 where Gades, although performing just a few extraordinary minutes, highlights the great concern of his whole life: social justice, a constant focus and source of his greatest pain. That is why this production had such strong social and even political content, being a monument of solidarity with the common folk.

At the end of that drama, Gades gives up a summary of his legacy with the conclusive reply of the common folk to the question «Who killed the Commander?», stating firmly «Fuenteovejuna, we all together did it, Sir». Gades left us on July 20th, 2004, and the candles of his vigil have burned out. But all together we celebrate him, because everything good is like the fire, which cannot be hidden from sight. Twenty years later, the legacy of Antonio Gades remains.

1 Translator’s note: “Fuenteovejuna” is a 17th century play by the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega. The play is based upon a historical incident that took place in the village of Fuenteovejuna in Castile, in 1476. While under the command of the Order of Calatrava, a commander mistreated the villagers, who banded together and killed him. When a magistrate sent by King Ferdinand II arrived at the village to investigate, the villagers, even under the pain of torture, responded only by saying “Fuenteovejuna, we all together did it, Sir.“

Translated by P. Young