Unknown cantes of Fosforito?

No, new songs are not, but they are unknown to the vast majority of the fans.

No, new songs are not, but they are unknown to the vast majority of the fans. It is not new news either. Already the good fans Andrés Raya and Dani Pino touched in his day, that we know, some data of which we will expose next. In any case, we understand that it is necessary to regroup the information, add what we can and put a little order for the knowledge of the interested amateur. Let’s go back a bit in time to be placing ideas, and the reader can situate himself in what we want to argue.

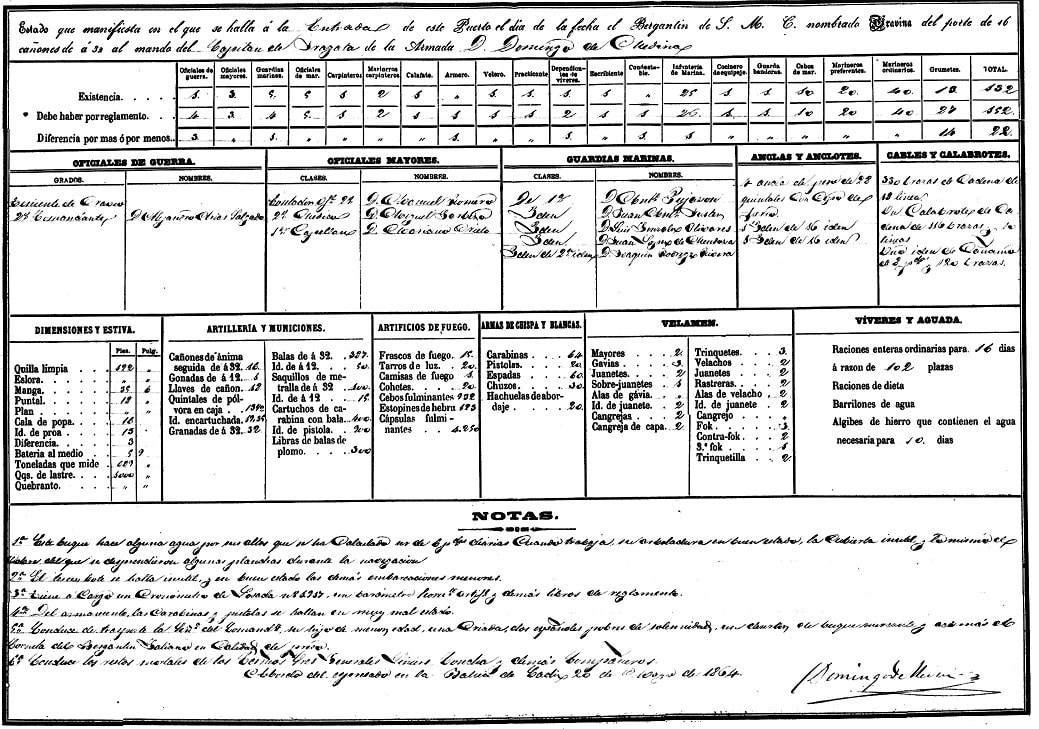

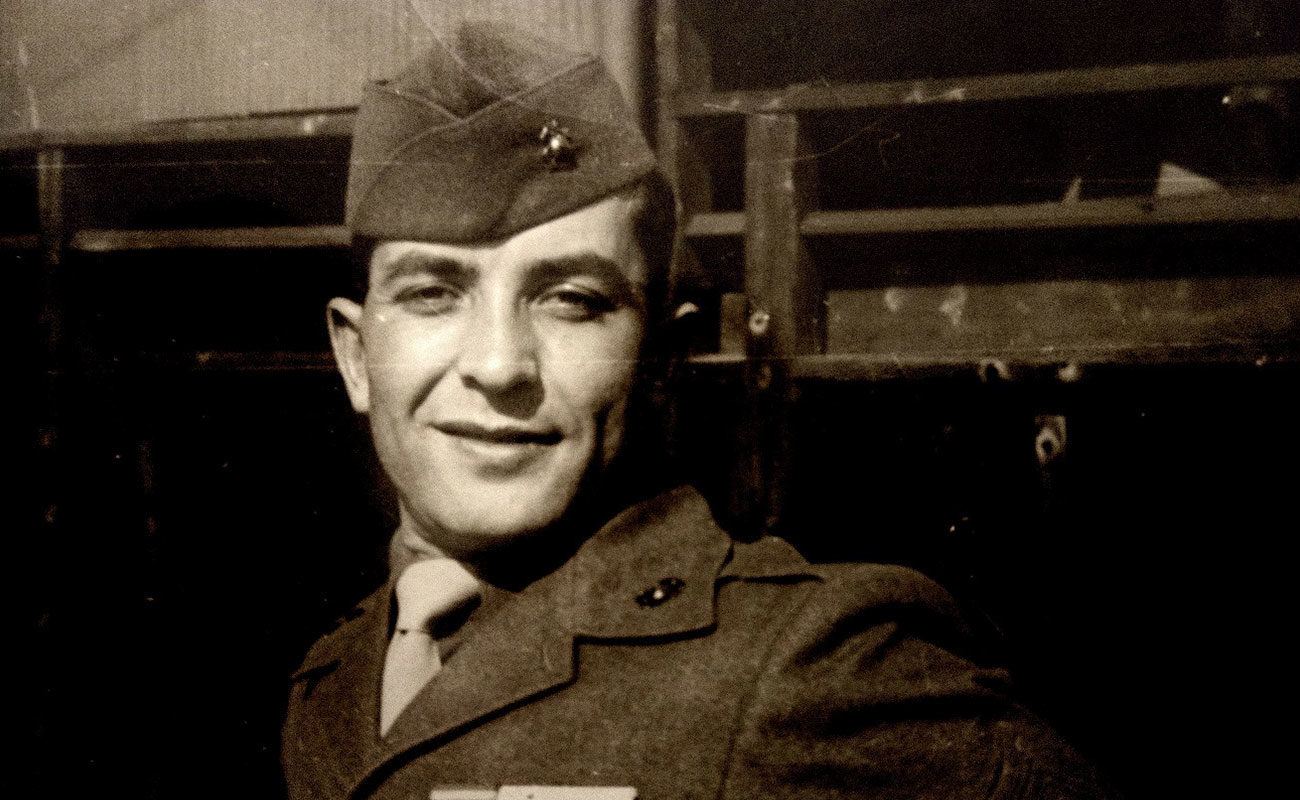

The official discography of Fosforito (Puente Genil, 1932) starts in 1956, the same year in which it devastates in the I Contest of Cante Jondo de Córdoba . In that year, at tenor and later to the contest, at the theater of La Comedia de Madrid, three EPs were recorded with the guitar of Vargas Araceli (Melgar de Fermental, 1907 -Madrid, 1971), one of the official guitarists of the contest. Two other EPs recorded in July of 1957 with the guitar of the Cordoban Juan Serrano (Córdoba, 1934), and Alberto Vélez (Cerro del Andévalo, 1921 – Madrid 2005), and that, apparently, they come on the market at 1958 with the Philips seal , whose recording rights are now in the hands of the multinational Universal .

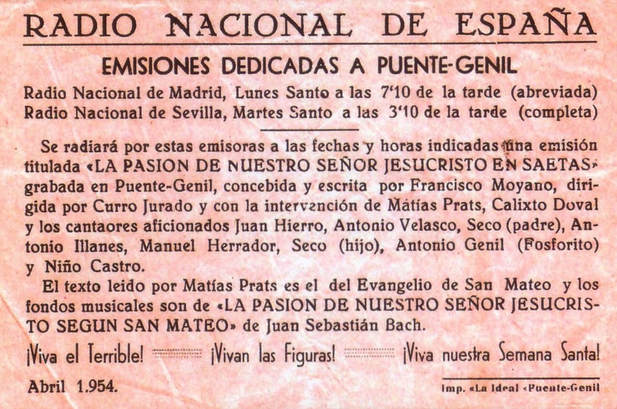

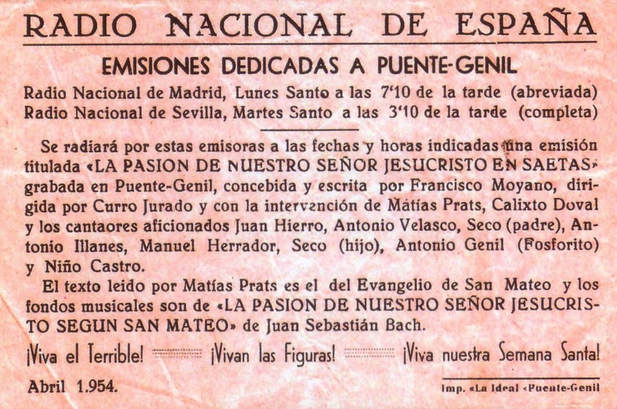

Before that record start, the voice of Fosforito it was registered for the first time in history – along with that of its countrymen Seco father and son, Juan Hierro , Antonio Illanes, Antonio Velasco, Manuel Herrador and the neighbor of province Niño de Castro – in a formidable adaptation, The Passion according to Saint Matthew in Saetas, what would the unparalleled Francisco Moyano . Live recording with “unofficial” character and very unknown outside Puente Genil.

This work was collected by the RNE microphones, and from the hand of the exalted Matías Prats (Villa del Río, 1913 – Madrid, 2004), who acted as narrator, in the spring of 1954 the Spanish homes were flooded by the most representative sounds and cantes of the pontanesa Holy Week. This sound document has become an authentic jewel of our culture, transcending the local scope due to the category of the interpreters ( Juan Hierro makes an entire exhibition), to the time when the beauty of the composition was already recorded. It also serves as an essential document for the study of the evolution of the genuine and indigenous old bridge of Puente Genil, the barracks . The “work” was happily edited by Agustín Moyano, son of Francisco, in 2009 for the Confraternity of María Santísima de las Angustias, with a magnificent sound quality.

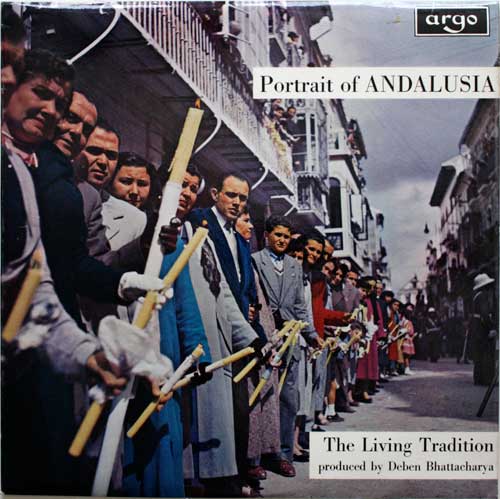

Between these two works is the little-known LP produced by the Bengali Deben Bhattacharya (1921-2001). This anthropologist, photographer, producer, ethnomusicologist, etc., assisted by Unesco, left an interesting field work in terms of recordings of “the music of the world”, which he developed throughout his life in about 130 albums. The LP PORTRAIT OF ANDALUSIA , within the series “The Living Tradition” , was published in London at 1968 under the British seal ARGO.

Bhattacharya , with recording devices at the ready-semi-portable and of 35 kg- and thanks to the poet Ricardo Molina , recorded in Puente Genil the audios of that LP at the end of March and the beginning of April of 1956. The work has no waste and is a real gem for Puente Genil, which has been recorded the sound track of some extraordinary years, in which Easter and flamenco were in full boil in the land of quince. We also discovered the young Antonio Fernández Díaz, just a few weeks before the famous contest in Córdoba, where he already exhibits his personality and imprint when it comes to mountain, soleá, alegrías and cantiñas. There is also a soleá of the very young Juli Córdoba , that by those years was a habitual saetero of the Brotherhood of Jesus Nazareno. Finally, we can not fail to review the imposing Soleá Apolá that gives us José Bedmar “El Seco” (Puente Genil, 1880-1970), sing directly from Dieguito Morón “El Tenazas” (Morón de la Frontera, 1852 – Puente Genil, 1933), the one that put flags in the Granada Contest of 1922. For another occasion, just for the sake of talking about cante, we will deal with these soleares and the possible branches that Silverio and his “disciples” could give more than probable soleares.

When it was published in London twelve years later, discs that arrive in Spain could be counted with droppers, so for many years this work remained in the shadow passing almost unnoticed. In any case, it escapes all logic that Deben Bhattacharya just record the cuts that appear in the aforementioned LP. From the hand of José Manuel Gamboa (Madrid, 1959) we learned from his book “A history of flamenco” (Espasa, 2005), which had been released a title CD Zingari. Route of the gypsies in which a seguiriya of Fosforito appears that was practically unknown by all, and two arrows of Juli Córdoba that we did not know either, and that as we said were recorded in Puente Genil in 1956. This teacher’s seguiriya, we include it in the work Puente Genil, land of cante, that La Droguería Music produced in 2016 for the town hall of Puente Genil, within the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Festival of Cante Grande “Fosforito ”

As we further researched Bhattacharya, our source for those “unheard-of” cantes, we must confess that it’s hard to have access to a clear and specific classification of his work, as we came across publications with different discographies in the USA and different European countries, with some tracks appearing in multiple albums from different years, and with very little information about them, if at all, resulting in a big jumble, on top of re-editions in CDs which don’t offer much information, either. All the sources we’ve researched hardly match at all, regarding the classification of this Indian musicologist.

We believe that the book-album The Gypsies: Pictures and Music From East and West (1966) was the first to feature such seguiriya, besides other “unheard-of” cantes, like a malagueña del Mellizo and one soleá which is different than the one featured in Portrait of Andalusia. It goes without saying that for us this was quite a find (which we don’t claim having made ourselves) and it’s a luxury to be able to enjoy of two additional cantes by this artist who a few years later would start one of the most brilliant careers in flamenco. As we mentioned in the previous paragraph, some of these cantes and some from Portrait of Andalusia show up in other albums under a different label and some re-editing.

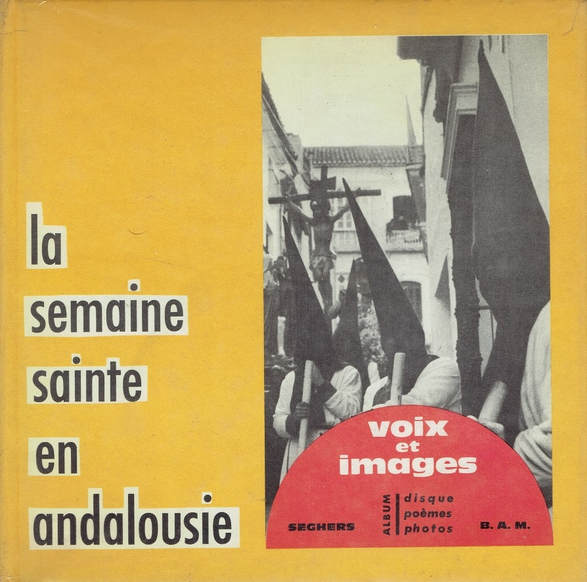

To finalize, for the moment, the list of “unheard-of” recordings, we must write about the book-album La Semaine Sainte en Andalousie, edited in Paris in 1960 by Seghers, first mentioned to us by the tireless aficionado Leonardo Velasco. It’s quite a treasure when it comes to its audio-visual content. On Side A we have what it seems like a series of saetas recorded on the street, until we realize that the background noises were added later. We got a big surprise when we found an unknown saeta by Juan García “Niño Hierro”, and another by Fosforito, which we wanted to write about. On Side B we have a wonderful seguiriya, also “unheard-of”, sung by Juan Hierro, and fandangos de Lucena sung by José Bedmar “El Seco”, which were used in the album Cantaores de Córdoba, edited by Caja Provincial de Ahorros de Córdoba in 1989, under the direction of the late Agustín Gómez.

Summarizing, we have four new cantes by Fosforito which the vast majority of aficionados never heard before (soleá, saeta, malagueña del Mellizo and seguiriya), besides the four cantes from Portrait of Andalusia(serrana, cantiñas, soleá and alegrías). Considering that we didn’t have access to all of Bhattacharyarecordings, we may in the future come across new “unheard-of” cantes from those 1956 recordings. El Seco, Juan Hierro and Fosforito himself may well have a nice surprise in store for us.

We would have liked to offer a contextualization of 1950s flamenco in general, and Puente Genil’s in particular, besides talking about the life of Fosforito at the time of those recordings, to be able to give our readers a better sense of the times, but we think we’ve already abused the space granted to us by ExpoFlamenco and we shall not overextend this text.

As I finish this article, I can’t hide the fact that I dream about having a compilation and re-edition of Fosforito’s complete recordings. Although the politicians may think that the favorite pastime of flamenco people is to complain about them, and they believe that behind every citizen there is a member of the opposite party conspiring to remove them from power, beyond their parallel reality there is the whole flamenco family, who between aficionados and professionals add color and content to the most representative cultural expression in our country. We can see that these politicians are bothered by us, little people, demanding good management and a real commitment to our culture, besides coherence with their own policies. Yet, how can the Junta de Andalucía award this master from Puente Genil the famed Golden Key of Cante, and then turn its back on his legacy? It’s not that we mean to give this award more importance than it deserves, but it’s infuriating that they’re not even attempting to rescue his discography, as it was done with Antonio Mairena and Niña de los Peines. They may be waiting for some private company to do this, yet they were the ones who gave the award and then took all the pictures, right? So, it’s time that they do something about this, because this is a matter of cultural interest. Can anyone understand this?

Apparently, the project of re-editing Fosforito’s complete recordings is currently in some box at an office of the Junta, and it doesn’t look like anyone cares about getting this done. Aren’t they ashamed about themselves for wasting precious time, as Fosforito is still with us and could be an advisor for this project? Is it necessary explaining to them that a work of analysis and dissection of that work is pending in order to fully understand and calculate this master’s contribution to flamenco? Just imagine the book which could come out of this project, where the protagonist himself might include further details and anecdotes about each recording, explaining the source and origins of cantes, etc.

There seems to be a problem in gathering Fosforito’s complete works, regarding the copyrights of each recordings. Well, as far as we know, the thick of the recordings belong to the labels Universal and Divucsa, which possess the rights (with their corresponding subsidiaries), of the old labels Philips and Belter, respectively, besides some recordings which may belong to Sony (inherited from RCA) and others such as Warner, via Hispavox. Despite of the particular interests of each record label, it’s perhaps the cultural department of the Junta which, guided by the artists himself, would be better suited to negotiate with all parts involved, more so if the initiative is taken by a neutral party, from an entrepreneurial perspective. Yet, the prospects are not very encouraging, as it looks like the government of Andalusia never created an agency to look after flamenco heritage and that the ball is in everyone’s court except in theirs.

Miguel Ángel Jiménez Valverde