Antonio Triana, a forgotten international star

Image If any curious aficionado of baile flamenco and its history tries to search for “Antonio Triana” in Google

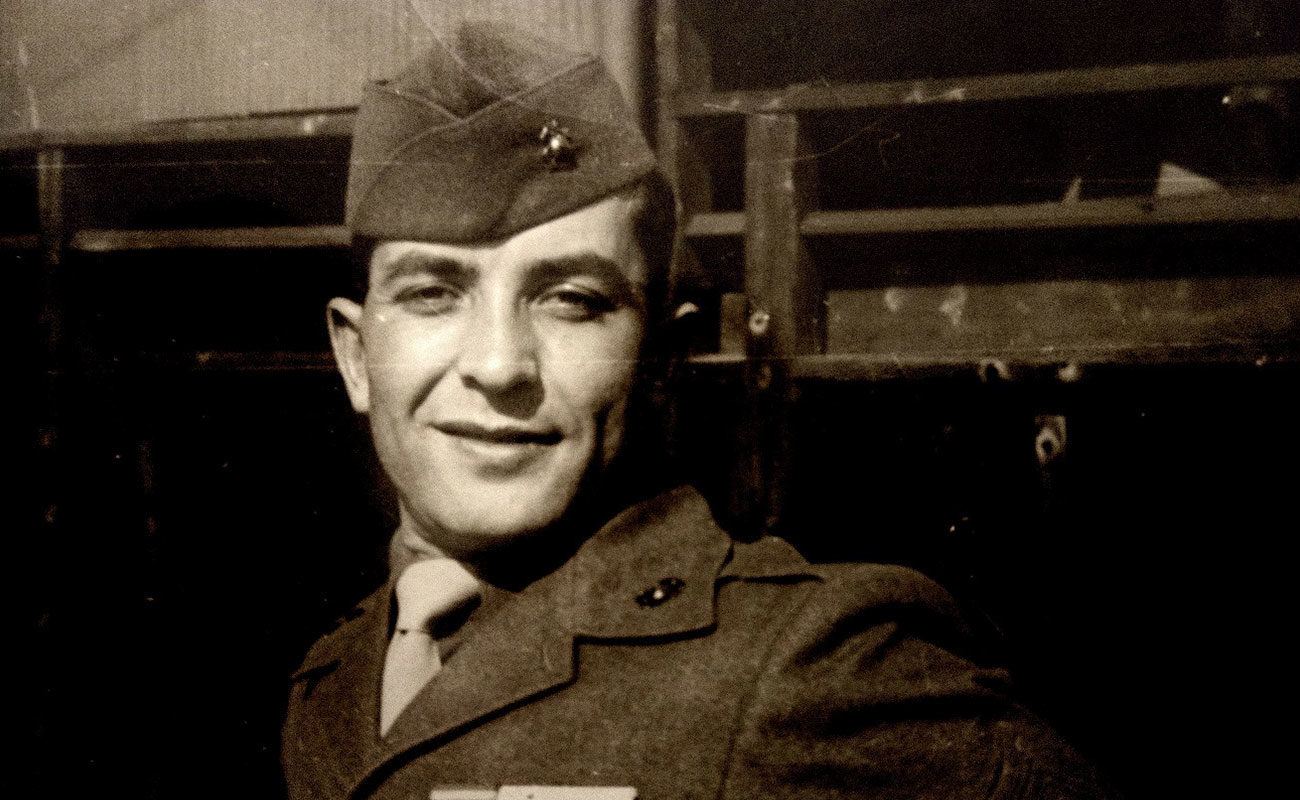

If any curious aficionado of baile flamenco and its history tries to search for “Antonio Triana” in Google or in any other search engine, they would barely find a few random images and some short biographies about him, often littered with errors. In Spain and within flamenco professional circles, few know anything about the career of Antonio García Matos, Antonio Triana, “partner of the stars”, who once achieved great artistic success and whose mortal remains rest in Hollywood’s Forest Lawn cemetery, next to the great stars of film. Even in detailed flamenco books about those years or in biographies of important artists with whom he shared the stage, such as Carmen Amaya (with whom he took America by storm) or Pilar López, to name a few, barely mention him in passing.

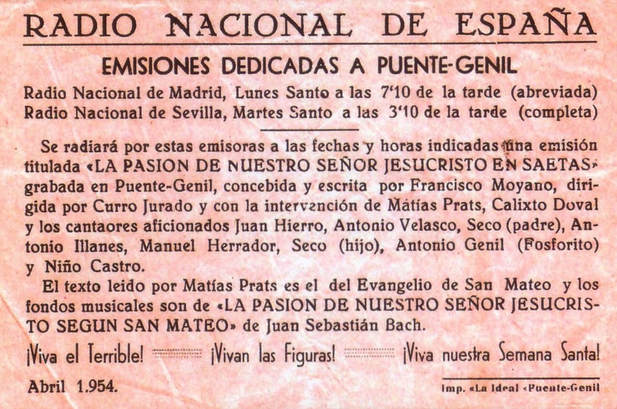

Last March 31 was the 29th anniversary of the death of this almost-unknown Antonio Triana, who performed in the big temples of baile with Argentinita and his sister Pilar, or with the above-mentioned Carmen Amaya. There is not even any commemorative tile honoring him in Triana, the district where he grew up, taking its name to all corners of the world. His life not only has enough artistic milestones to justify such honor, but it’s also rich in travelling adventures.

When he was just a child, Antonio inadvertently began his training in baile tutored by the celebrated maestro Otero, who partnered him with La Quica and named their debuting act “the miniature couple of baile”. Already famous in his neighbourhood for his cleverness, innate talent and irresistible grace, he soon achieved acclaim in Seville, where he was referred to as a child prodigy of baile, as attested in a poster advertising a performance in the Summer Theater, where Niño Medina was the main act. Later, he would perform with Frasquillo (La Quica’s husband, bailaor from Viso del Alcor) at the Novedades and the Kursaal cafes. The renowned flamencologist José Blas Vega wrote about his performance on the night when a young Niño Ricardo officially debuted in Seville.

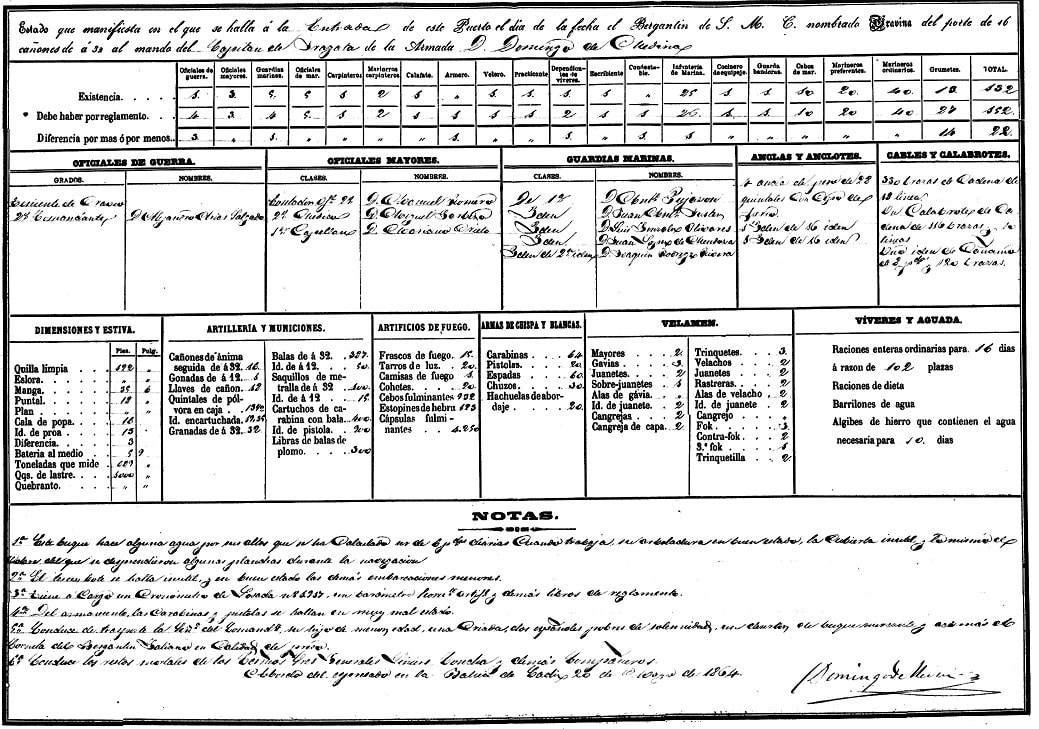

With the decline of the cafés cantantes and against his parents’ wishes, he enlisted as a steward in the Cabo Villano cargo ship, bound for New York, pursuing his dream: becoming a famous bailaor and movie star. That was at the end of 1924, many years before Lorca wrote about the inhuman soul of that megacity where Antonio threw himself in, without any schooling or even a basic knowledge of English, after deserting the ship where he worked as a steward. With the help of Juan, a barber from Málaga, he found lodging at Spanish Harlem, and after attending a reception for the Spanish painter Zuloaga, he found work in the company of Amelia Molina (who was also from Seville and trained by Otero), with whom he debuted in Broadway.

When he was touring in Texas, he learned about the death of one of his idols, heartthrob Rudolph Valentino, something which touched him deeply, prompting him to quit Molina’s company and head to Hollywood, where he always wanted to live. His rise to the top was meteoric, as within a few months he managed to make a name for himself in Los Angeles’ emerging mecca of film and dance. With Lope Vélez, he was a protagonist in El Gaucho, a highly anticipated movie starred by Douglas Fairbanks, the premier of which was attended by the crème of Hollywood in the just-opened Chinese Theater of Sid Grauman. That success (enthusiastically applauded by one Antonio’s idols, Charles Chaplin) allowed him to secure a supporting role in “La Mexicana”, the first short film in history to feature sound, where the song “Cielito Lindo” was first recorded and where, incidentally, a young Xavier Cugat took part in the musical takes. However, when Triana started savouring the sweet taste of success, the American Immigration Agency noted that the emerging star Antonio Triana was no other than Antonio García Matos, the steward who a few years earlier had deserted his ship in New York. On the advice of United Artists’ legal office, he decided to leave America before being deported.

Antonio TrianaEl GauchoLa Mexicana

Antonio Triana con Argentinita y Pilar López

That’s how he ended up back in Seville during its Exposición Iberoamericana, where he arrived as an artist of international renown. The doors of the main theaters of the city opened for Antonio, but without a doubt the milestone of this period was his role in Falla’s Amor Brujo ballet. Triana was invited to play the role of Carmelo, in a cast starred by Argentinita, Pilar López and Rafael Ortega. The premiere, which was also Argentinita’s performing comeback, took place in Cádiz’s Gran Teatro Falla, with Lorca and Falla himself among the public. Fleeing the Spanish Civil War, which began on the birthday of Antonio’s brother (the celebrated maestro Manuel García Matos), he went to Paris, where destiny would partner him again with Argentinita and Pilar López. He joined their company, which caught the eye of the American impresario Sol Hurok (agent of the Bolshoi Ballet and many other renowned artists), who took them for a long tour in New York. Yet, Argentinita started to experience the symptoms of the illness which would eventually take her life, which caused the company to disband and prompted Antonio to seek other opportunities. That’s when his association with Carmen Amaya started.

Triana and Hurok were the main architects of Carmen Amaya’s success in America. It’s odd that the person who sent the telegram to this bailaora from Catalunya, offering her the contract which brought her to New York, is only considered a secondary player in that feat. Antonio was in charge of all of the company’s choreographies and he masterminded a show full of classical numbers of Spanish dance, from Albéniz to Granados, without which it would have been impossible to succeed in Carnegie Hall. After dazing New York, the company went on an American tour which ended in Los Angeles, with a double performance in Hollywood Bowl, where they shared the program with Frank Sinatra. The possibility of going on tour in South America came up, but Antonio declined it. At last he was back in Hollywood, where he always wanted to be.

One of the happiest times in Antonio’s life began after this artistic break with Carmen Amaya. He got back in touch with the big studios, with directors of the stature of Boris Petroff, Anthony Mann and George Cukor asking Triana to setup the dance scenes of their movies. To have an idea of how well integrated Antonio was in the city’s artistic circles, all we have to do is recall his work in The Snows of Kilimanjaro, one of Hollywood’s biggest movies in the 1950s.

A few years ago, the renowned auctioneer Doyle New York sold an oil painting by Nicholai Fechin for $392,500. The painting title was “Antonio Triana as a Gypsy”, a portrait that the cosmopolitan Russian painter made of his friend. Antonio befriended many other renowned artists, such as the painter Will Foster, artist of the Beat generation, or Francis Lenn Taylor, father of Elizabeth Taylor and art dealer with whom, according to Antonio’s daughter Luisa Triana, “he loved to talk about art and smoke cigarettes“. Gene Kelly was a self-declared big fan of Antonio Triana, and he was a regular in his dance lessons at the Di Rea studios and also in the poker games he hosted in his house, where Luis Buñuel would often show up. These are just brief examples of the many personalities who befriended and worked with Triana during his long, successful years in Los Angeles.

After he retired from the stages and film, Triana spent the last years of his life in El Paso, Texas, where he had a dance academy until his dead, when he was 83 years old. He led a family life with his wife, Rita, and their two children.

To make justice to the achievements of this unique bailaor (and those of his dauther, Luisa, who debuted under the guidance of Argentinita in Buenos Aires, when she was seven years old), we plan to publish a book about their careers. To achieve this, we have undertaken a long research, together with the journalist and dance critic Marta Carrasco, and we’re currently in the writing phase. We hope to release this book at the end of this year.

Alberto Guillén