The current state of flamenco in Málaga

When Málaga’s Bienal de Flamenco was created in 2005

When Málaga’s Bienal de Flamenco was created in 2005, by the initiative of the Town Council, presided at that time by Salvador Pendón, we all congratulated ourselves, thinking happily that, at last, Málaga was once again cantaora, after many years of silence when we lived off nostalgia and past glories. During its short life, the Bienalprovided the city with flamenco shows, publishers and record labels, and a variety of flamenco events that hadn’t been seen here for many years. Sadly, that was a very brief experience and we ended up facing the desert after a beautiful mirage.

Considering that this year we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Juan Breva’s death, and the 60th anniversary of the peña named in his honor, the landscape of flamenco in Málaga is quite desolate. The Peña Juan Breva, a model for peñas all over Spain, was founded on October 2, 1958. Even if today it’s not as influential as in the old days, the initiatives to commemorate its anniversary, which are interesting and at a level that the occasion demands, haven’t yet secured the necessary institutional or financial backing, which is truly deplorable.

Yet, I think it’s even worse that no celebrations are planned for the 100th anniversary of the death of an artist like Juan Breva, who died on June 8, 1918, a cantaor who achieved the highest acclaim during his lifetime and whose contribution to flamenco is beyond any doubt, even if there’s much research pending to be done about this subject. Although there is a program of activities honoring Breva in his birthplace (Vélez-Málaga), up to now, as far as we know, there’s nothing being planned in the province’s capital.

Continuing the analysis of the current state of flamenco in this city, we find that Málaga’s Town Council, presided by Elías Bendodo, brought back the Bienal de Flamenco, attempting to find favor with the flamenco community. In practice, it’s an event spread in time, without any apparent cohesion or sense of unity and which, having a meagre budget, requires its management staff to do veritable juggling acts to make it happen in a dignified way, revealing the scant interest in flamenco that Málaga’s politicians really have. When it comes to the Junta de Andalucía, things aren’t much better, as Málaga only gets a few leftovers like the series Flamenco Viene del Sur and some events, increasingly scarce, at Museo Picasso, so we can only ask ourselves where is the supposed promotion and preservation of flamenco that the Junta agreed to undertake when this art form was declared a World Heritage Treasure by UNESCO in 2010.

Málaga’s University, in turn, has been working these last few years on renewing and promoting its Flamencology Chair, organizing workshops, summer courses and funding research, but the fact is that it has not much visibility. Regarding private initiatives, there has been some praiseworthy efforts to give the city a variety of tablaos where the art of flamenco can be enjoyed, yet these are too little known, few and far between. Big companies such as Unicaja, in turn, barely consider flamenco in its programming of cultural events.

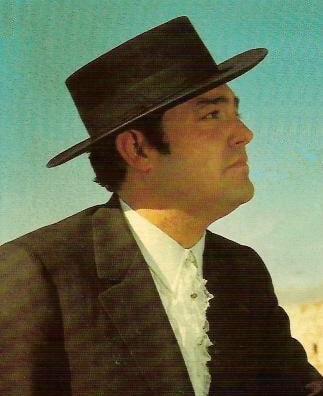

Antonio de Canillas

Regarding the flamenco artists of Málaga, they’ve realized since long ago that the city has not enough room for them (or even any interest in making room), so they’ve had no choice but to leave the province in order to continue developing and making a living off their art. We currently have a superb lineup of artists from Málaga who have been widely acclaimed and are becoming essential for the most prestigious flamenco events, such as Daniel Casares, Rocío Molina, Antonia Contreras, La Lupi and Curro de María, Rocío Bazán, Alfredo Tejada… Yet, this happens away from this city, which proves that it doesn’t possess the fabric to embrace them. The few artists who remain in Málaga either accept their fate and barely survive with minor performances, or reinvent themselves to be able to succeed, such as in the praiseworthy cases of Paco Javier Jimeno and Ana Fargas, who have created their own school, El Patio, in Estepona, where they train artists in cante, toque and baile, besides producing their own excellent shows.

Yet, without a doubt, the most outrageous case of all is that of the veteran of Málaga’s cante, Antonio de Canillas, an artists who must be remembered for his life devoted to cante, for having been the link between two generations (those who were born at the end of the 19th century, whom he met and learned from, and those born in the middle of the 20th century, who in turn learned from his experiences); and also for giving shape to the saeta malagueña as we know it today. In 2012, the Federación de Peñas Flamencas honored him with a tribute where he felt the warmth of his colleagues, and where Málaga’s mayor, Francisco de la Torre, committed to award him the city’s medal as a token of appreciation. In these five years, even a website was launched, Antonio de Canillas, honores en vida, urging the authorities to fulfill their promise. Yet, it happened what we feared: Antonio de Canillas passed away on April 3, never having received such award, whose proceedings were started just one week before his death. At least we can take comfort in the fact the he was aware that the bureaucratic proceedings for the awarding of the city’s medal had been started.

I don’t want to finish this article without pointing out that specialized flamenco critics have long disappeared from all media in Málaga. I firmly believe that critics are always necessary and that they have an important role, as long as it’s done with respect, professionalism and constructively. The reality is that the few flamenco shows performed in the city are never analysed and properly judged, and there are no critical voices who denounce or applaud the decisions that are taken about flamenco in Málaga.

As you can see, the situation leaves a lot to be desired.

Lourdes Gálvez del Postigo Calderón