Forty years is the time I’ve been away from flamenco. I came back almost by accident, perhaps because I’ve reached retirement age, when we use to long for the things from the past that meant something in our lives. I don’t have a detailed vision of the current state of flamenco, just an idea about the whole genre, provided by new friends I’ve made in the social networks and, particularly, by old friends I’ve met. What I’ve noticed is that today’s world of flamenco is, in some respects, very different, for better or worse, than the one I left, and in other respects it’s characterized by a stagnation which was already apparent back then, and which, oddly, still persists.

I’ve been surprised, for example, by the rehabilitation of Pepe Marchena as the great flamenco artist he was, being one of those links in the hierarchy of cante flamenco’shistory. I didn’t expect it, frankly. I thought that the unfair oblivion he had been subjected to was going to last forever, considering how things were when I steered away from flamenco. His character has been rehabilitated, more than his particularly style of cante, as has been rehabilitated, to put it this way, the non-Gypsy line in cante flamenco, the one represented by Silverio-Chacón-Marchena-Morente, in contrast with the so-called Gypsy-Andalusian line imposed by Antonio Mairena. Today, both currents coexist, even as the latter seems to prevail, ideologically.

I’ve also come across an upsurge in baile and flamenco guitar, which clearly have been leading the way, in terms of creativity. Baile has continued its centuries-old international popularity, even as it’s no longer that traditional flamenco dance that used to be taught in baile academies, but a whole avant-garde creative movement featured in all major dance events around the world. We can say the same about flamenco guitar, which has been popularized around the world by a new generation of tocaores who have managed to give it an international projection.

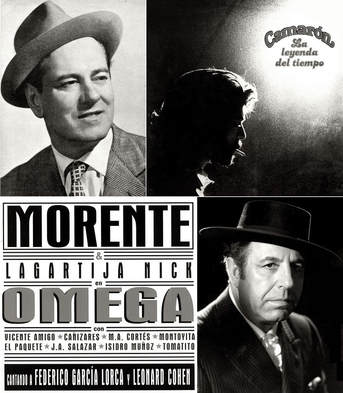

Then there is cante, and that’s where it hurts. What I’ve noticed (although I may be wrong) is that cante is going through an unprecedent creative stagnation. The last significant contributions that are mentioned are Morente’s Omega, released over 20 years ago, and Camarón’s La Leyenda del Tiempo, released almost 40 years ago, besides the contributions by Lebrijano and Manuel Molina, from about the same time. Cante is not being renewed, as it was expected, considering the above-mentioned examples. What is worse, flamenco aficionados don’t even demand such innovation. I mean old aficionados, many of them flamencólicosburdened with increasing melancholy and orthodox authority at each passing year, and still immersed in the “Mairena Statutes”, according to which everything in cante has already been invented and all we have to do is look back, love it and respect it, denying the new generations any attempt at innovation or creativity. Cantehas fallen into a conformism which has debased it. This has made young people steer away from it, particularly where it was born, in Andalusia, and it has also caused its artificial preservation based on public subsidies, required for its survival despite its agonizing state. Nothing could be more contrary to a popular music that was always characterized for its vitality and financial autonomy.

Antonio Villarejo Perujo