Daniela Tugues: «I want to use all my knowledge to help flamenco flourish in Venezuela»

The Venezuelan artist forged her way as a flamenco ‘bailaora’, dance director and choreographer from Lebrija. “Watch flamenco. Experience flamenco. Imitate it initially until you learn the basics, but then be yourselves,” she says

During the summer of 2022, Tugues showcased her spectacle, Multiversos at la Caracolá festival. She produced ‘Flamencura Latina’ in Lebrija. Daniela Tugues Correa: flamenco ‘bailaora’, dance director, choreographer, ‘biodanza’ pioneer, poet, lyricist and dream repairwoman. She says she got into flamenco because it’s there, the same words used by George Mallory a century ago when asked why he wanted to climb Everest. She featured in Carlos Saura’s film, Flamenco, directed musicals here and there, fell in love with a man from Lebrija, and now is set on proudly representing flamenco in her home country, Venezuela. “Artists and schools focus on surviving, rather than paying for courses in Spain or bringing teachers over to give classes, and that’s been going on for a while. But living in this bubble has given the Venezuelan woman a new aesthetic and a strong sense of authenticity,” she says.

– Your Instagram profile describes you as a ‘Hispano-American mestiza artist’ as well as a ‘dance director, choreographer and dance performer’. Sounds good! Which label do you most identify with?

– Dance performer.

– You were born in Venezuela. How did flamenco find its way to you?

– In Venezuela, our Spanish roots touch almost everyone and almost all of our culture. Having been an oil-exporting country, we got rich. Through this, we became a hub for migration, employment and a destination for flamenco artists and Roma families, many of whom made a living through flamenco, giving classes and through shows. In the 70s, wealthy entrepreneurs brought flamenco artwork from Spain and stayed for extended periods, like when Camarón de la Isla came to our country and didn’t want to leave. I wouldn’t be surprised if the lyric ‘Caribbean sun, hit me in the face, I want to go back tanned to Spain,’ from his ‘bulería’ was written on our beautiful beaches. In fact, the ‘cantaor’ Pedro Genil was one of the many who fell in love with a Venezuelan. He shares countless stories about the origins of flamenco in Venezuela, including ones featuring his colleague, Camarón. With regard to how flamenco found its place in my life, I can simply say that it was there. I wanted to dance folklore, I asked in a school nearby to my house and they said: ‘There’s no folklore here, but we have flamenco, which is similar.’ That’s how it found me and 45 years later I’m still a part of it.

– And how did your flamenco shoes end up in Lebrija, and the flamenco hub that is Seville?

– Through love. I fell in love with a man from Lebrija who lives and breathes flamenco, so not so much to do with work.

«You walk through Seville whilst the man painting the walls sings a ‘fandango’. The cleaner sings. Everyone claps. The city breathes flamenco and dances to ‘bulerías’. In contrast, outside of Andalucía, it’s hidden amongst the rocks and you have to be veryyyy dedicated to find it and practice it properly»

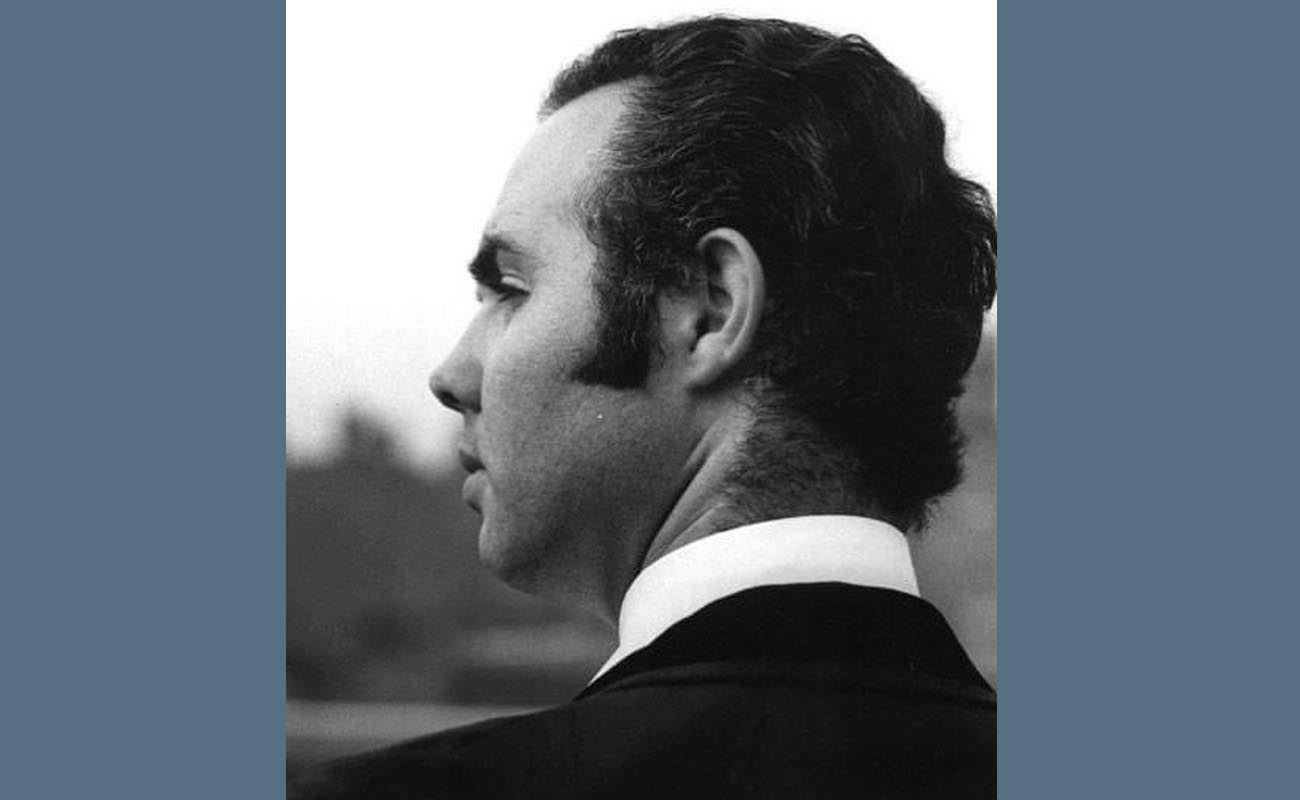

La bailaora Daniela Tugues, fotografiada por Paco Rosso – Antidanza en el Parque María Luisa, Sevilla.

– In 2022, you participated in the Caracolá festival in Lebrija. How did you find it?

– It’s a special treasure. The organisers wanted to make it an open-air event in the Juan Diaz de Solis square. They wanted to do something different, so those less familiar with flamenco would come, and that’s how I ended up getting called. They said, ‘we want you to do your thing’. My thing is when flamenco is merged with Hispano-America, our own fusion. That’s the reason I was at such a prestigious and traditional Andalusian festival. I was immensely satisfied with the appreciation for my work.

– Have you attended any other major flamenco events?

– At the 19th Bienal de Sevilla 2016, I was an artistic director, lyricist, and choreographer. I composed the music and the lyrics for the opening ‘sevillanas’ in the musical Sirenita entre mares andaluces, starring flamenco artists such as El Torombo, Manuela Ríos, Juan José Villar, Juan Villar hijo and Ángeles Toledano amongst others. In 2008 and 2009, I was on the poster at Casa Patas, Madrid for a week. In 2002, I was invited to the 1st Festival Latinoamericano in Costa Rica. I also performed at the Festival de Escuelas Flamencas in Miami, USA.

– Do you think it’s especially difficult for a Latino artist to find their way professionally in flamenco in the birthplace of the art form, Andalusia?

– I do think so, above all when you speak your own language. But I also think if you work hard and dedicate your life to it, you can become respected, although it takes time.”

– How would you define flamenco in your country, Venezuela at this moment in time?

– I think flamenco in Venezuela has declined because of the economic and social crisis in the country. Artists and schools focus on surviving, rather than paying for courses in Spain or bringing teachers over to give classes, and that’s been going on for a while. But living in this bubble has given the Venezuelan woman a new aesthetic and a strong sense of authenticity, although the technique may not be the best and there is still a lot to learn.

– Are there any artists who stand out to you as professionals?

– There are Venezuelans who dance flamenco and do stand out internationally like Mariana Martínez, Carmen Garza, Mariana Darias, Daniella Hernández y Stefany Vivas amongst others. Those who dance a fusion of styles or less purist styles like Siudy Garrido, Ana Loynaz, Patricia Cinquemani… Within the country, everything is very raw but done with a ravenous desire. There are school heads with ample knowledge of the flamenco world like, Gabriela Alfonzo, El Torbellino, John Molina… Younger figures include Daniel Riera, La Polaca, La Cayetana, Ynes Mary Pérez and more.

– Are there good quality teachers and enough students to demand this level of teaching, particularly in dance?

– Yes, there are teachers who can teach flamenco to a good level, but we are missing singers and guitarists. The very foundation of flamenco is its music, and what we have in that area is insufficient. I went back to Venezuela on the 3rd of December 2022 and what most stimulates me is helping my friends who are fighting for Venezuelan flamenco. I want to use the techniques I’ve learned in Spain as well the as 45 years I’ve spent studying the dance to help people. I can combine this with everything I’ve learned through professional practice. I want to use everything I know to help flamenco flourish in Venezuela.

«Listen to flamenco during the day, at night, in the shower. Study its origins. Watch flamenco. Experience flamenco. Imitate it initially until you learn the basics, but then be yourselves. Respect your elders, because they pathed the way for us. Write about it. Stay disciplined, humble and open to learning from the major players in the field»

– In 1994, who took part in the film Flamenco by Carlos Saura. Tell us how you became part of that incredible ensemble of artists and what the experience meant to you?”

– Firstly, it was an incredible acknowledgement of my discipline, hard work and arrogance to be cast. Then again it was also a lesson in humility and professionalism to meet people in film like Carlos Saura and Vitorio Storaro or in music like Isidro Muñoz, José Antonio Rodríguez and Pepe de Lucía, and in dance like Merche Esmeralda. To see them operate as such pure professionals, without any fuss, fully absorbed by their tasks, working with humility, without shouting and with utter respect to the plan. That for me was the most important thing. I was a young 26-year-old. Very lucky, of course. It all felt like school for me. What did it mean for me? The recognition of my talent opened so many doors. The film was an important reference for anyone who was interested in me, as summed up by an interview with a Venezuelan media company: ‘How good must a Venezuelan woman have to be to be recognised in a documentary about flamenco in Spain?

– Do you see flamenco through a different lens living in Andalusia compared to anywhere else in the world?”

– Totally. You walk through Seville whilst the man painting the wall sings a ‘fandango’. The cleaner sings. Everyone claps. The city breathes flamenco and dances to ‘bulerías’. In contrast, outside of Andalucía, it’s hidden amongst the rocks and you have to be veryyyy dedicated to find it and practice it properly.”

– You are also a poet and lyricist. Do you combine these art forms with the ‘jondura’?”

– Yes, totally. As I said before, I wrote lyrics for the music at the Bienal, I’ve sent lyrics to flamenco lyric competitions, and I’ve worked on flamenco musical adaptations of Disney films which have been shown in Argentina. This is one of the lyrics from La Sirenita in ‘Guajira’ form:

Love is crazy

with good mates

with honest friends

devoid of sanity.

They speak sweetly

they’re good at heart

they bide their time

to count the stars

out at sea there are beautiful

reflections of heaven

– What message would you have for flamencos in Hispano-America and the rest of the world?”

– Listen to Flamenco during the day, at night, in the shower. Study its origins. Watch Flamenco. Experience Flamenco. Imitate it initially until you learn the basics, but then be yourselves. Respect your elders, because they pathed the way for us. Write about it. Stay disciplined, humble and open to learning from the major players in the field. But above all be good people, because although you may not get all the success you want, your success will be present in your heart and in your peace of mind.

Translation by Matthew Osborne