Japan, Flamenco of the Rising Sun (2)

Japan’s impressive passion for flamenco didn’t happen overnight

So, how do you think this happened? The flamenco flower didn’t bloom overnight, I suspect. Imagine going to bed on a Wednesday night in Tokyo, unaware and ignorant of the immense flamenco reality. Then waking up on Thursday, opening the white Japanese curtains and, lo and behold, there’s the Garden of Venus, with hundreds of local aficionados looking for the flower they love, trying to emulate Manuel Torres or Antonio Chacón por malagueñas.

No, it definitely didn’t happen that way. Yet, we can follow a series of historical milestones which had a decisive influence in the birth of that passion, or rather interest, for flamenco things. We have to remember that baile and guitar have always served as the battering rams for cante whenever flamenco has gone beyond Spain’s borders. They have the advantage of rhythm, visuals and the universal language of music, without the cultural and language barriers that exist outside the gates of Andalusia. Interest in cante, if it happens at all, comes after.

«Recent studies mention sixty thousand flamenco students spread among six hundred and fifty flamenco academies in the country. Just in Tokyo there are more flamenco academies than in all of Spain»

La Argentina and Pilar López

The first time that a Spanish dance company performed in Japan was in 1929, courtesy of Antonia Mercé La Argentina. This happened in Tokyo, part of an international tour featuring the re-enactment of El Amor Brujo y Andalucía. She was joined by Pastora Imperio, Vicente Escudero and Miguel Molina. Among the public, a young dancer of Japanese butō dance was shot with Cupid’s invisible arrow and fell in love with Spanish dance forever. His name was Kazuo Ōno (1906 – 2010), the unrivalled master and guru of that oriental art form. Almost fifty years later, in 1977, Kazuo premiered his production Admiring La Argentina, which was awarded the Japanese critics’ prize of that year.

Spain’s golden age of cante was coming to an at the time when La Argentina was touring Japan. Manuel Centeno, José Cepero, Juanito Mojama, Niño Marchena and Niño de Caracol were being acclaimed on the stages, while Manuel Vallejo and Niña de los Peines were well-established stars, following the steps of Antonio Chacón, who had just passed away, and the brilliant Manuel Torres, who was approaching the end of his career. The first flamenco slate records arrived in Japan in those years, a historical footnote without any meaningful impact. It was the guitar of Carlos Montoya (1903-1993) which became etched in the calendars of Japanese aficionados, as he performed a spectacular tour around the archipelago in 1932. The Japanese people were fascinated by flamenco guitar. The seed has been planted.

Then, a war between brothers and two nuclear bombs littered streets and hearts with rubble on both sides of the globe. It wasn’t until the 1960s when the first flamenco companies toured Japan. Pilar López took her impressive world tour to that country in 1959, forever enthralling who would then become the best Japanese flamenco dancer of all time, Yoko Komatsubara. The land then became fertile ground for Manolo Vargas, Rafael Romero El Gallina, Merche Esmeralda, Cristina Hoyos, El Güito, Paco de Lucía and Camarón de la Isla to gather the empire of the Rising Sun’s rich harvest in the following decade. They would inspire a generation of Japanese-born artists, the first Japanese bailaores of international renown. Yasuko Nagamine, Masami Okada, Shoji Kojima or the above-mentioned Yoko Komatsubara, among others, didn’t think twice before travelling to Andalusia to sharpen their skills.

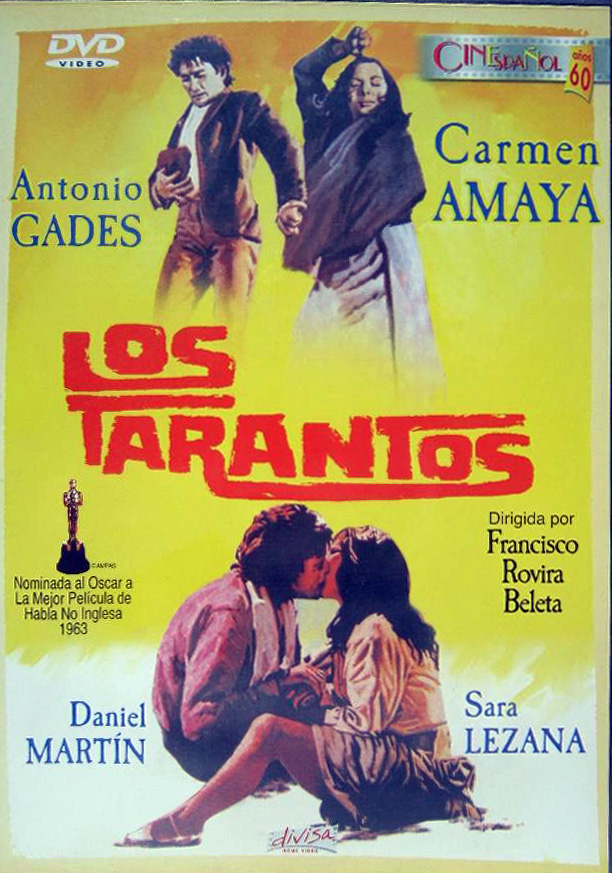

Antonio Gades, Los Tarantos and Carmen

What about Antonio Gades? The importance of this bailaor from Alicante in the popularization of flamenco in Japan can’t be understated. He featured in two landmark movies. In 1963, the premiere of Francisco Rovira-Beleta’s film Los Tarantos, starring Carmen Amaya and Antonio himself, caused a veritable commotion among the Japanese public, which then began travelling to Spain to know first-hand that unique art genre. In 1984, another movie, Carmen, directed by Carlos Saura, again featuring Antonio Gades, joined by Cristina Hoyos, Pepa Flores y Laura del Sol, was awarded the best-film prize in Japan. From then on, Antonio Gades and Japan embraced each other forever. This bailaor toured the archipelago with his company in 1989, and again two years later.

«Mario Maya, Angelita Vargas, Matilde Coral and Manuela Carrasco made baile flamenco so popular in Japan that Japanese people started to consider this art form as part of their own culture»

It didn’t take long until this love for flamenco became reciprocated. In 1988, the Bienal de Flamenco de Sevilla invited several Japanese artists. On that occasion, cantaor Masanobu Takimoto El Cartero de Osaka accompanied the baile of Keiko Suzuki, Eiko Takahashi and Atsuko Kamata Ami, who in 1995 became the first foreigner to be awarded a prize in the Concurso Nacional de Córdoba. Most Spanish flamenco artists typically travel to Japan at least one or twice every year. Mario Maya, Angelita Vargas, Matilde Coral and Manuela Carrasco made baile flamenco so popular in Japan that Japanese people started to consider this art form as part of their own culture. Cante also became popular, led by Pansequito, Aurora Vargas, Rancapino, Esperanza Fernández and Remedios Amaya. Virtually every renowned flamenco guitarist has performed in Japan, so it’s pointless to try to make a list.

The world’s second flamenco superpower

Nowadays, Japan is the world’s second flamenco superpower, just behind Spain, and it’s perhaps the first country in the world regarding flamenco productions. Recent studies mention sixty thousand flamenco students spread among six hundred and fifty flamenco academies in the country. Just in Tokyo there are more flamenco academies than in all of Spain. To have an idea of how strong is the Japanese interest in flamenco, bear in mind that there are two national flamenco federations: the Asociación Nipona de Flamenco (ANIF), meant for all aficionados interested in the development of this art form, and the University Flamenco Federation, founded in 1995, encompassing over ten universities and financed by the yearly fees of its members, who every summer lodge together in the futuristic city of Tateyama to enjoy flamenco around the clock.

Asociación Nipona de Flamenco. Photo: ANIF website

Among all factors that have helped to promote flamenco in Japan, we cannot leave out the Cervantes Institute of Tokyo, opened in 2007. It’s the largest of all the Cervantes Institutes in the world, and it’s part of the organizing committee of the Concurso de Flamenco, created in 2018 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Spain and Japan. The winners of the first two editions were given the opportunity to travel to Spain and perform at Tablao Los Gallos in Seville. The Institute has also organized the four editions of the famous Flamenco Summit in Japan, which was held for the first time in 2012.

About the artists, we’ll have to wait for another article.

«Pilar López took her impressive world tour to that country in 1959, forever enthralling who would then become the best Japanese flamenco dancer of all time, Yoko Komatsubara. The land then became fertile ground»

Top photo: Miwako Tada – Tablao Flamenco Japón

Pingback:May ’22: Flamenco Marketplace this Weekend, Artist Interviews, & More! – Flamenco Vivo Carlota Santana 11 May, 2022