When Granada went to Canada

Gracita, Chiquito, Marote and Joaquín, “cuatro puntalitos” like the verse of soleá says, representing the particular personality of flamenco in Granada. The show has aged well in my memory, it was powerful flamenco with the aroma of folklore that lost its innocence on the way to sophistication.

Fifty years ago there was a flamenco show. Three-thousand five-hundred miles from Spain. In Canada to be exact, where pockets of avid flamenco fans enthusiastically follow the artform. Expoflamenco, conceived and maintained from Vancouver, is a fine example. But why bother to talk about performances long ago applauded and forgotten? Well, because it seems important to remember inspired artists who gave so much to flamenco, and whose influence continues to this day, although their names may not be remembered.

It’s no secret I have a soft spot for Granada flamenco, which is routinely upstaged by the flamenco of western Andalucía, that of Seville, Jerez and Cádiz. Oddly enough, non-Spanish individuals unfamiliar with flamenco, assume Granada to be the epicenter of the genre, hot-spot of the elusive “real” flamenco people dream of experiencing. Perhaps the presence of the breath-taking Alhambra that draws two million visitors each year is enough to relegate flamenco to second place for tourists.

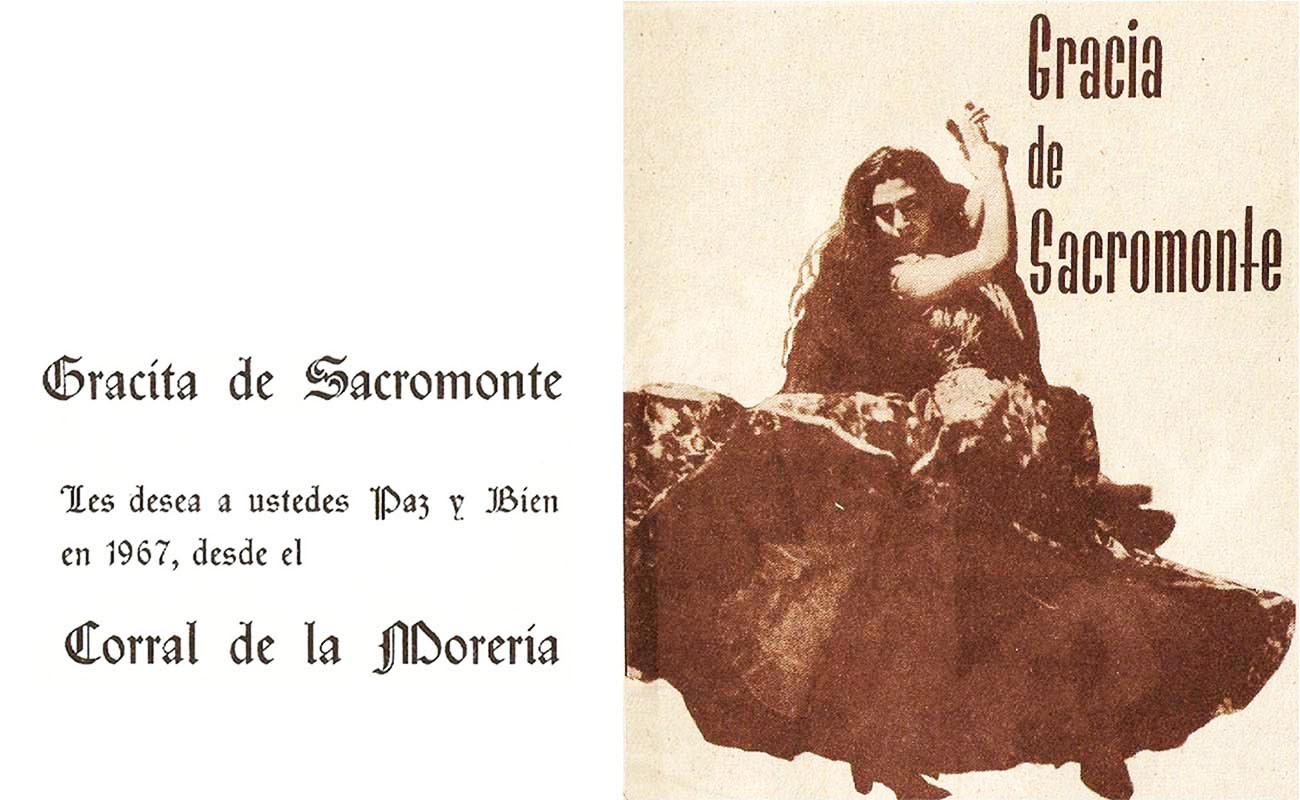

So, synchronize your watches and set the GPS: it’s the summer of 1970 and we’re visiting the Montreal Expo. At the spacious auditorium of the Spanish pavilion is a show that stars Granada’s Gracia Quero Hidalgo [1939-1981], Gracita de Sacromonte, a unique artist and cult figure with a complicated family history that kept her from developing a mainstream career.

I was working nightly next-door at the Café d’Espagne, with the company of Simón Naranjito (from Valencia, hence, the nick), so I had a season pass that allowed me to catch all three daily performances of Gracita’s group. In between shows, being in the dressing-room was like a free-wheeling master-class in Granada flamenco. Those tangos they do, so different from what you hear in Cádiz, Triana, Málaga or Extremadura, cantes I’d never heard before, not even on the old María la Canastera and Manolo Amaya recordings.

Gracita danced and sang with strength and intensity cultivated in the caves of Sacromonte. She had been featured five years at Madrid’s Corral de la Morería, and toured internationally. Her exotic beauty is mentioned in every description of her performances, and her finger-snapping was so crisp and strong, its sound crackled throughout the largest venues. Her singing was instinctive and untrained, which made it all the more appealing. She would come on with the Zorongo del Sacromonte which she sang and danced. Her voice is playing in my head right now:

Llévame sobre tus brazos,

sobre tus brazos morenos

Por el camino adelante,

hasta que encuentres el cielo

[Carry me aloft with your brown arms, straight-ahead until you reach the sky]

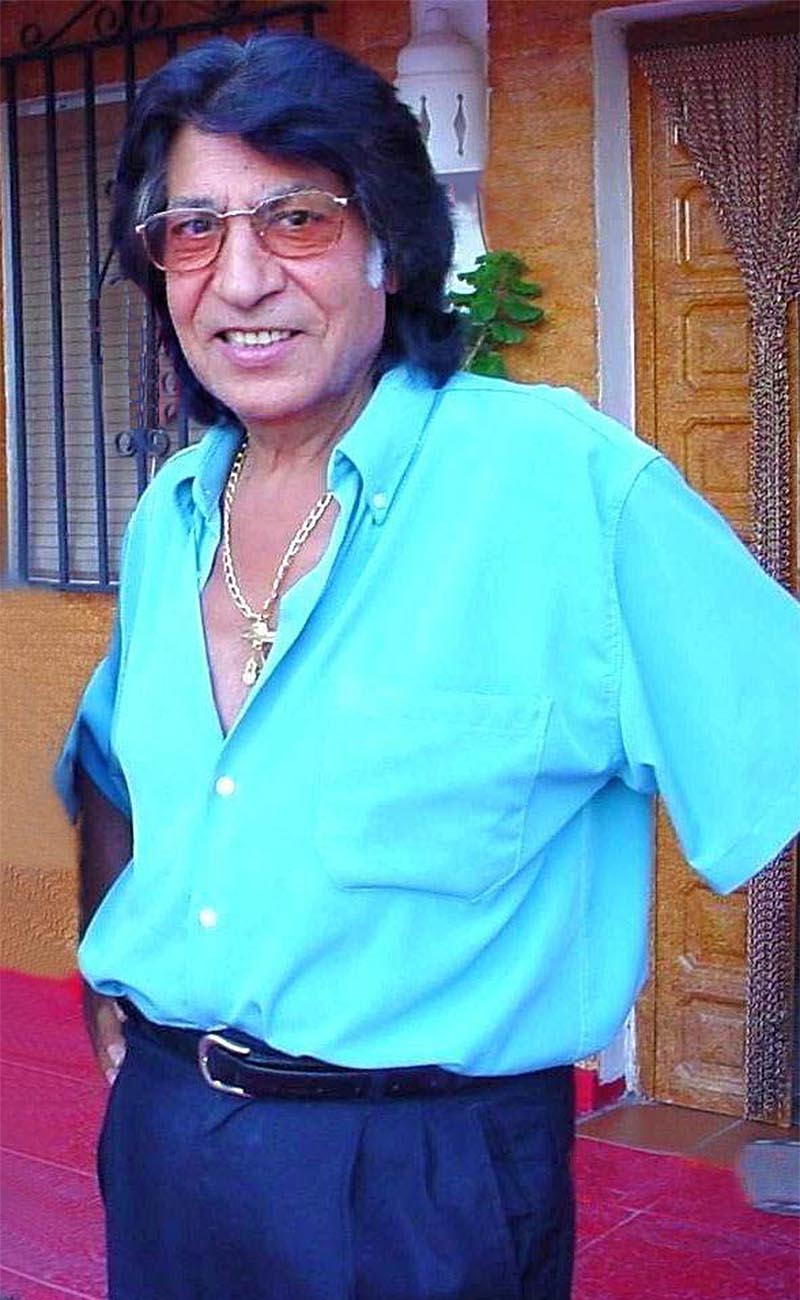

Giving form and coherence to the Granada presence was the great guitarist Juan Maya Marote [1936-2002]. Even after all these years, I still remember the excitement of sitting in the hush of the darkened auditorium. Suddenly, Marote’s guitar would unleash a crisp E-chord with that crystalline continuous strum of his that laid down the law and took no prisoners. Six strings like six razor blades slicing through the air making time stand still.

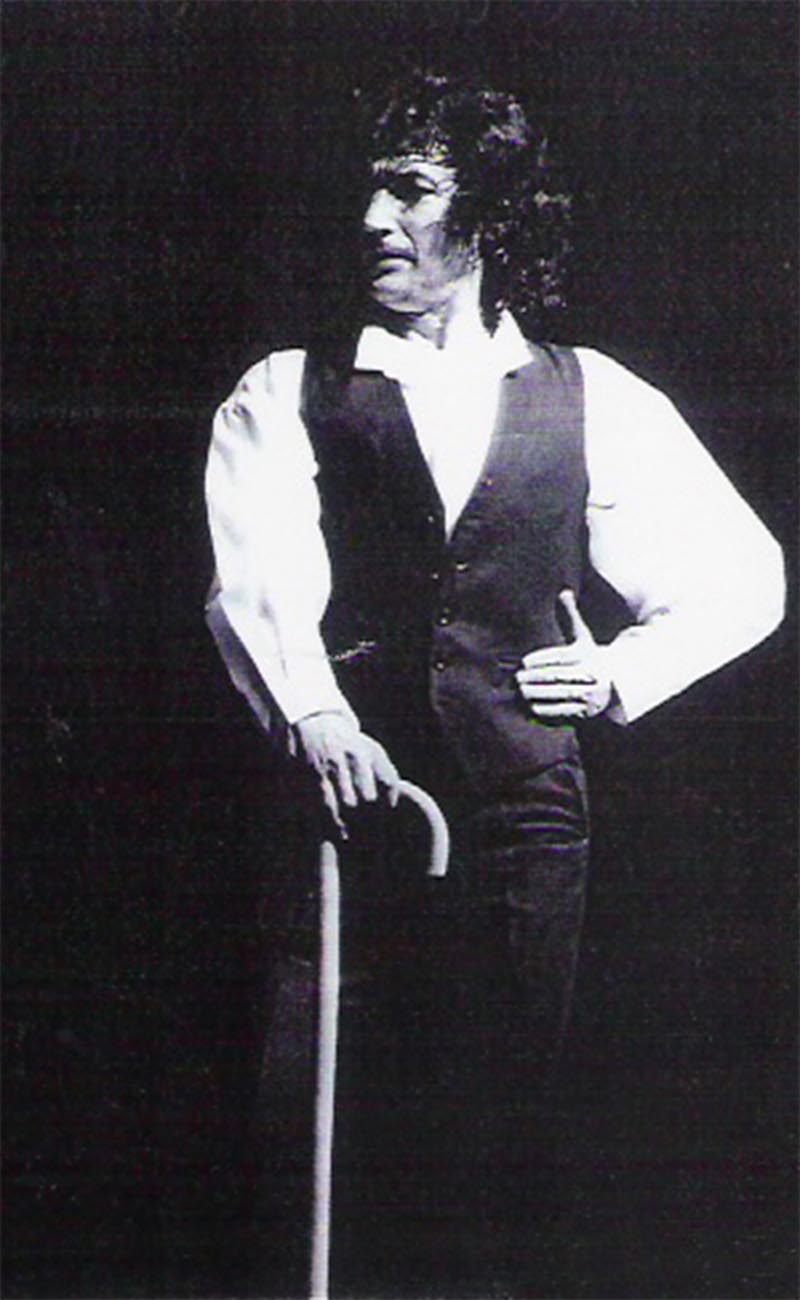

Defending the Granada school of dance, Joaquín Fajardo [1945] was a miracle of contained power, tense elegance and surreal precision that made every moment “important”. A sort of intensity that was nearly unbearable, like a spring about to snap. In addition to being one of the best male flamenco dancers of his generation (although he relocated to Mexico before making his name in Spain), Joaquín sang well, and played a thoroughly credible guitar.

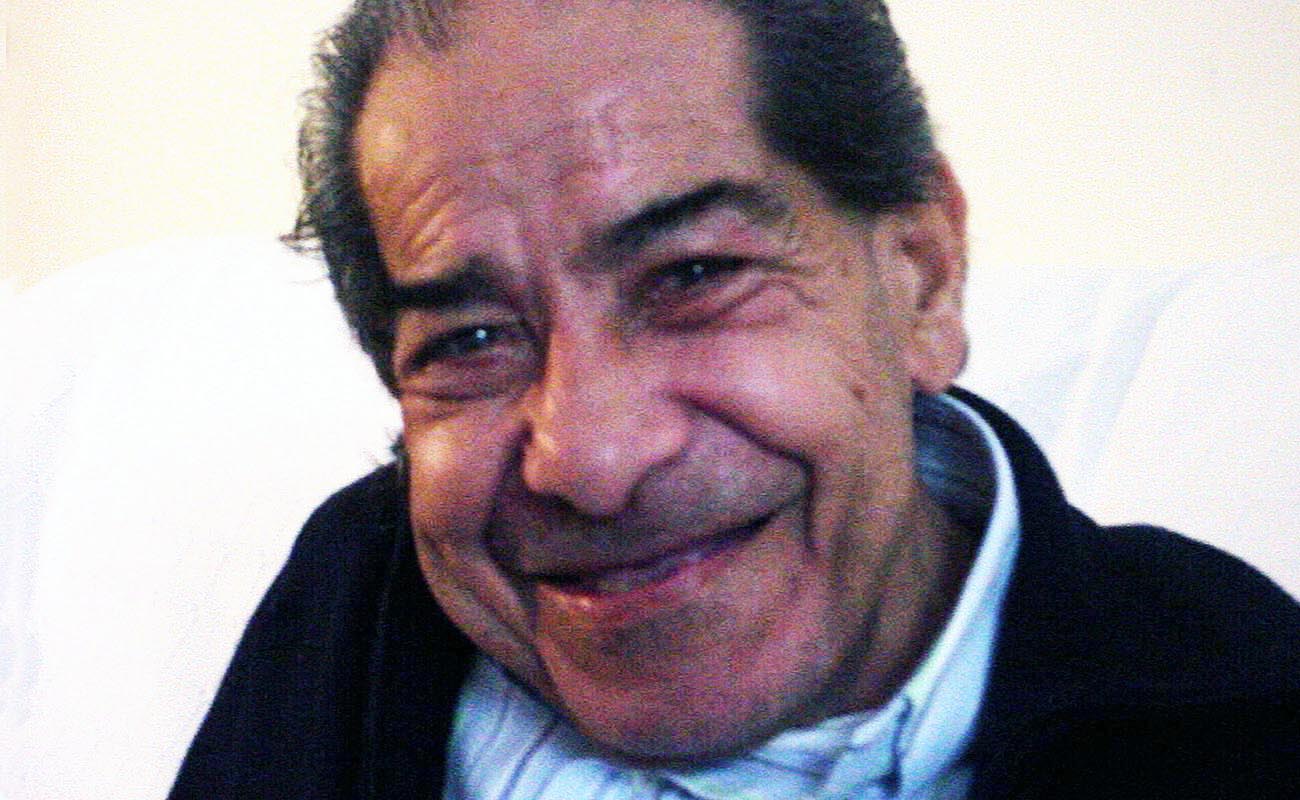

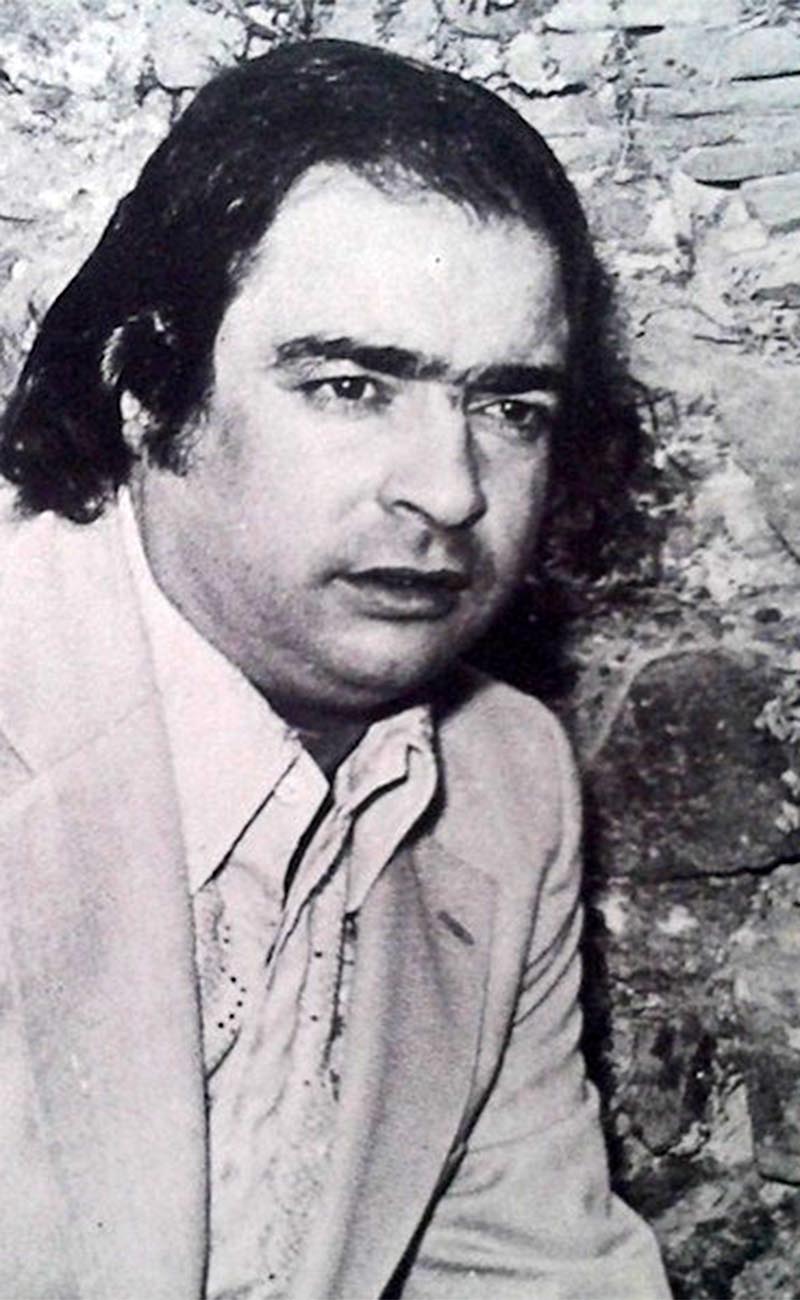

Singer Manuel Torres Torres “Chiquito de Osuna” [1936-1993], who lived most of his life in Granada, had been performing in the zambras of Sacromonte since adolescence, and was a fine interpreter of the most classic forms. His great rhythm and clean delivery were the perfect seasoning to round out the Granada presence in Montreal that year.

There were two excellent male dancers who did a fine farruca duet, and three well-trained women who opened the show with cantiñas. I don’t remember much else of the program, except the rumba fiesta finale in which Gracita did a raucous version of Achilipú that was popular at the time. Second guitarist Pepe el Vallecano ably supported Marote and brought the number of artists in the company to ten.

Gracita, Chiquito, Marote and Joaquín, “cuatro puntalitos” like the verse of soleá says, representing the particular personality of flamenco in Granada. The show has aged well in my memory, it was powerful flamenco with the aroma of folklore that lost its innocence on the way to sophistication. A contemporary feel that never seemed contrived.

* This article is dedicated to my admired friend Curro del Albaycín.

Gracita de Sacromonte. Foto: publicidad del Corral de la Morería

Gracita de Sacromonte. Foto: publicidad del Corral de la Morería

Joaquín Fajardo. Foto: FajardoFlamenco

Juan Maya Marote. Foto: Estela Zatania

Chiquito de Osuna. Foto: DiscoGS