Utrera and its Potaje

There’ll be no Potaje Gitano this year, no souvenir wooden spoon to take home for the collection. But the Utrera flamenco feeling is no fleeting commercial phenomenon. It’s day-in, day-out food for the soul with its laid-back swing, natural delivery and subtle intensity.

Crazy times these. Decades from now, 2020 will be remembered and studied, and young scholars will write theses based on memories heard from their great-grandparents. The year they cancelled Holy Week. Just like that. After getting the towns of Andalusia white-washed and the viewing stands erected, it all had to be dismantled. And there was no Seville Fair either. No Feria del Caballo in Jerez… in fact, just about every event, public and private, including weddings, baptisms and other family celebrations we flamenco folk cherish, was gone.

Then, just a few days ago, the Hermandad de los Gitanos de Utrera announced the news we knew was inevitable. A microscopic bit of protein, a virus, is depriving Utrera of its Potaje Gitano for the first time in 63 years. The pioneering festival that began so humbly, went on to define an era that may now be in danger of extinction. The Potaje’s format became the model for many dozens of similar events throughout Andalusia and elsewhere. The summer festivals that finally brought generous salaries, recognition and dignity to artists who no longer had to do the circuit of theaters with cheesy variety shows that often included comedians and girlie acts, have been suspended for reasons of public health.

That first Potaje was held May 15th, 1957… just a handful of people and a few tables for 60 people. Evolutionary times for flamenco. In France the first flamenco anthology in history would soon be released, and in Madrid, the first modern tablao, Corral de la Morería, opened its doors. In Algeciras a ten-year-old boy called Paquito was dreaming the guitar music destined to become the flamenco sound track that would eventually usher in a new millennium. Carmen Amaya was revealing her extraordinary intensity to foreign audiences still struggling to distinguish flamenco from the Mexican Hat Dance, and a singer called Antonio Mairena was engineering his master plan to rescue traditional cante from years of public indifference, while the first tourists from abroad were beginning to test the waters of Spain’s beaches and learning to pronounce “paella”.

«Decades from now, 2020 will be remembered and studied, and young scholars will write theses based on memories heard from their great-grandparents»

Since the Potaje’s humble beginnings, the festival has grown exponentially to include nearly all the major flamenco performers of each era, with tributes for the most relevant figures. The format would eventually morph into a mega event for some two-thousand people, many of whom would watch the show on giant screens of the type we see at rock concerts.

Perhaps the most wrenching moment I remember of the many Potaje festivals I’ve attended was in 2004 when Bernarda de Utrera was presented with a bouquet of flowers “on behalf of Fernanda”, her illustrious sister, who was seriously ill at the time. You could almost hear the lumps forming in throats throughout the spacious athletic field when Bernarda tearfully accepted the bouquet.

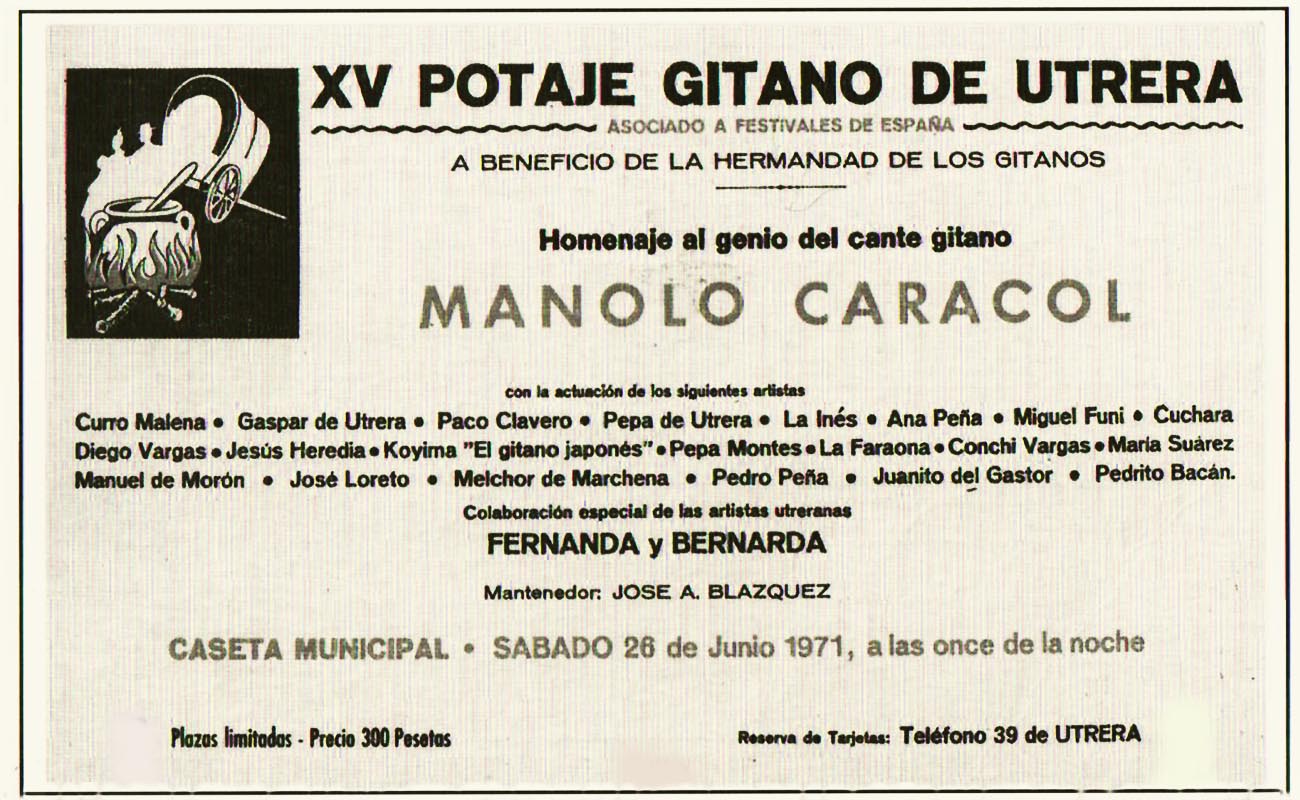

Fifty years ago, in 1971, the fifteenth Potaje Gitano de Utrera was held, and dedicated to Manolo Caracol. Manuel Peña Narvaez, one of the founders of the Potaje, remembered the occasion as one of the greatest editions of the festival. Caracol came accompanied by Melchor de Marchena, Pilar López, his three daughters and son Enrique, as well as his son-in-law Arturo Pavón for whom a piano was installed on-stage for the first time in a Potaje.

Highlights of that edition were made into a recording: XV Potaje Gitano de Utrera en Directo (1971) included in the series Cultura Jonda. Fernanda and Bernarda can be heard at their best with bulerías that prove just how powerful this form can be – no frivolity here, just neat packages of angst that get right inside your head. Gaspar’s masterful unique delivery takes siguiriyas and martinete to a higher plane, and he gives tientos depth that few other singers are able to locate. Also on the recording, Pepa de Utrera, Miguel Funi, Jesús Heredia and Enrique Ortega, Caracol’s son, among others.

There’ll be no Potaje Gitano this year, no souvenir wooden spoon to take home for the collection. But the Utrera flamenco feeling is no fleeting commercial phenomenon. It’s day-in, day-out food for the soul with its laid-back swing, natural delivery and subtle intensity.

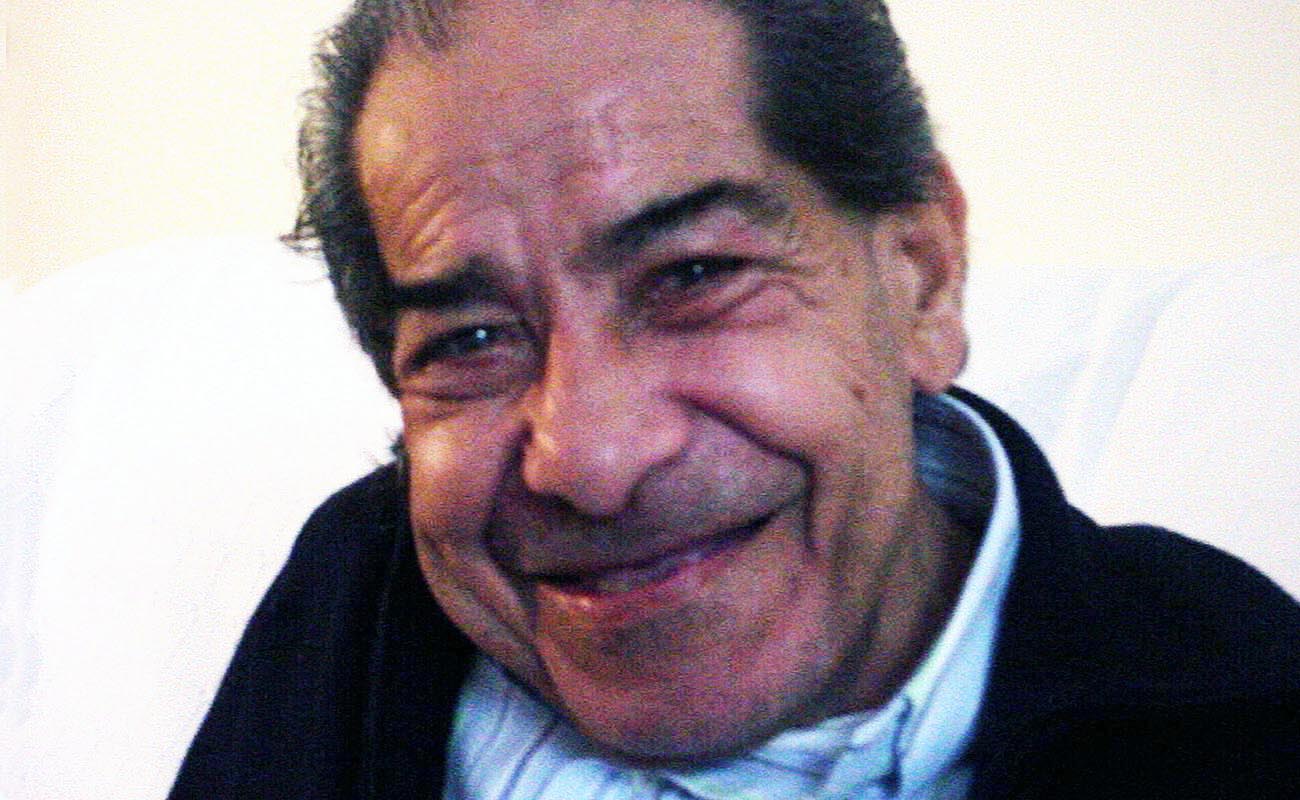

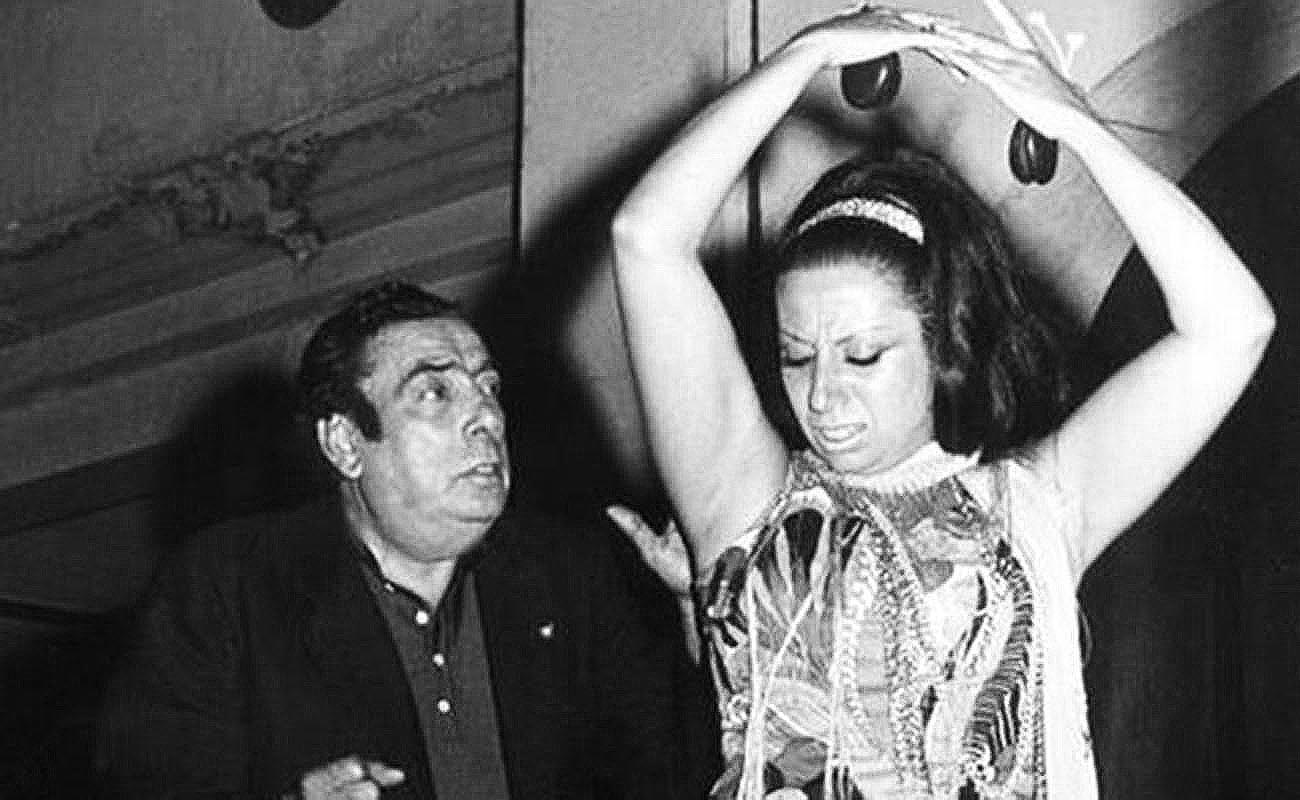

Manolo Caracol y su hija Luisa. Potaje Gitano de Utrera. Foto: José Jiménez

Cartel del Potaje Gitano de Utrera 1971.

Portada del álbum XV Potaje Gitano de Utrera, 1971.