The integrity and power of Diego Clavel

Dedication, wisdom, integrity and a long honest career have earned him the admiration of his town and of flamenco followers everywhere. He will be honored at the 52nd edition of the Reunión de Cante Jondo of La Puebla de Cazalla.

How do you describe a flamenco singer? Well, they’re usually extravagant, dynamic, expansive and bohemian with lots of attitude. Many nicknames have reflected this supposed quirkiness… El Chalao, El Loco Mateo or the revered Manuel Torre often referred to as the Majareta, nicknames which in Spanish affectionately refer to a touch of madness.

But we need to put all that aside to speak of Diego Andrade Martagón, “Diego Clavel”, one of the natural resources of La Puebla de Cazalla (1946), mentored and encouraged by painter and poet Francisco Moreno Galván who did the same for José Menese. Diego Clavel is best described as discreet, cerebral, reserved, knowledgeable and profoundly devoted to the art-form that brings us all together here at Expoflamenco.

To call him studious would be a gross understatement. Among his numerous recordings are monographic masterworks that include the volumes devoted to siguiriya with 17 styles, malagueña with 47 styles (no, that’s not a misprint), 60 fandangos de Huelva, 85 styles of soleá and 33 styles of mining cante, all including details of origin and author, with the poetic wisdom of Diego’s proviso: Where do the cantes come from? I think that question is impossible to answer. Flamenco singing was, is and will always be there, and each person gave, gives and will give the best interpretation possible.

I don’t think there’s any other singer whose identity is so closely linked to a single specific cante, namely the siguiriya of Manuel Molina. Not Lole’s Manuel, but “Señór” Manuel Molina as he was often called, a nineteenth-century singer from Jerez. Diego worked up a strikingly dramatic version based on a sort of muted scream that has become his trademark.

Diego Clavel wisely administers his unmistakable delivery without shouting or histrionics, internalizing emotions, only releasing the power of his voice at key moments to communicate his personal take on the most classic sort of cante. An “aficionado” in the Spanish sense of eagerly delving into the most arcane forms, his repertoire includes many little-known or even obsolete cantes. Browsing my own chronicles of his performances I see he announced such elite items as “malagueñas of the maestro Ojana which I learned from Vallejo, and one of Chacón’s ending with the cante of la Rubia de las Perlas”, or the “taranta of Rojo el Alpargatero with verdial of Vélez” in addition to soleá apolá, fandango of Puente Genil, trillas, liviana, serrana and María Borrico and all the standard forms you would expect from a professional of his caliber.

I remember the year in La Puebla when Diego arrived on stage with the help of crutches, heroically determined to defend the tradition of ending the Reunión de Cante Jondo at 5 or 6 in the morning with a round of tonas. He not only delivered his usual high level, but was the only singer to show up for that grueling moment.

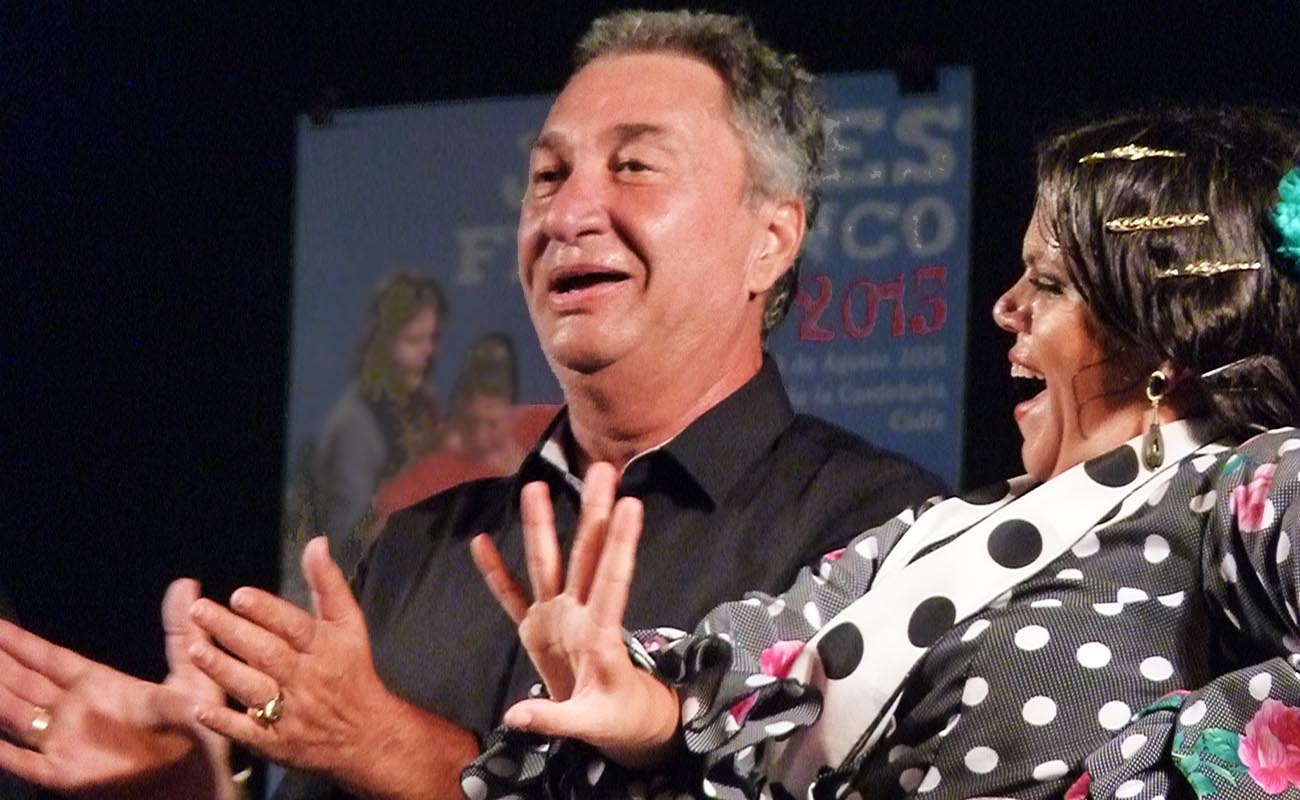

Worthy of a chapter unto itself is Diego’s astonishing bulerías dance. Who could ever imagine such a reserved elegant artist capable of such authentic country-bumpkin humor!

A half-century ago, on July 10th, 1971, Diego Clavel sang for the first time in the Reunión de Cante Jondo of La Puebla de Cazalla. I was there. And so were Fosforito, Terremoto, Fernanda and Bermarda de Utrera, Curro Mairena, José Menese, Juan Habichuela, Parrilla de Jerez, Pedro Peña, Matilde Coral, Rafael el Negro and Farruco. That’s a lot of flamenco all bunched up in one place, typical of the festivals of the era. Diego went on to sing in forty editions of the venerable event. Dedication, wisdom, integrity and a long honest career have earned him the admiration of his town and of flamenco followers everywhere. He will be honored at the 52nd edition of the Reunión, well-deserved recognition for an impeccable career.