The fiesta is serious business

Without festive flamenco, without the street humor of the bartender on the corner, or the unmistakeable cheeky behaviour inherited from the historic “majos”, jondo pomp and circumstance is missing its yang.

By now, most people reading this know I’m deeply interested in the much under-rated festive type of flamenco, mostly bulerías, but tangos and tanguillos as well. I hope to deal with this vast topic in occasional articles that not only recall past figures now nearly forgotten, but which highlight the importance of this facet, such an integral part of the flamenco persona. In Andalusia, neither Córdoba nor Jaén nor Huelva nor Almería developed a repertoire of festive flamenco. That leaves us with Málaga, Granada, Seville and Cádiz, in particular the latter two, to take up the slack.

It’s simplistic to consider siguiriyas “pure”, and bulerías not. Some music historians have theorized that the figure of the “festero”, interpreters specialized in the festive forms of flamenco song and dance, suggests a culture of get-togethers, which in turn enhances the entire flamenco ecosystem, including the more sedate forms. Possibly over-compensating for past social injustice, writers, notably Lorca, cultivated the romantic flamenco cliché of tragedy and darkness, to the detriment of the fiesta concept. In fact, it seems the greater the suffering and deprivation of any given setting, the more intense the fiesta. I observed this while interviewing field workers who used to subsist in the terrible conditions of makeshift barracks called gañanías, where some of the liveliest flamenco fiestas took place.

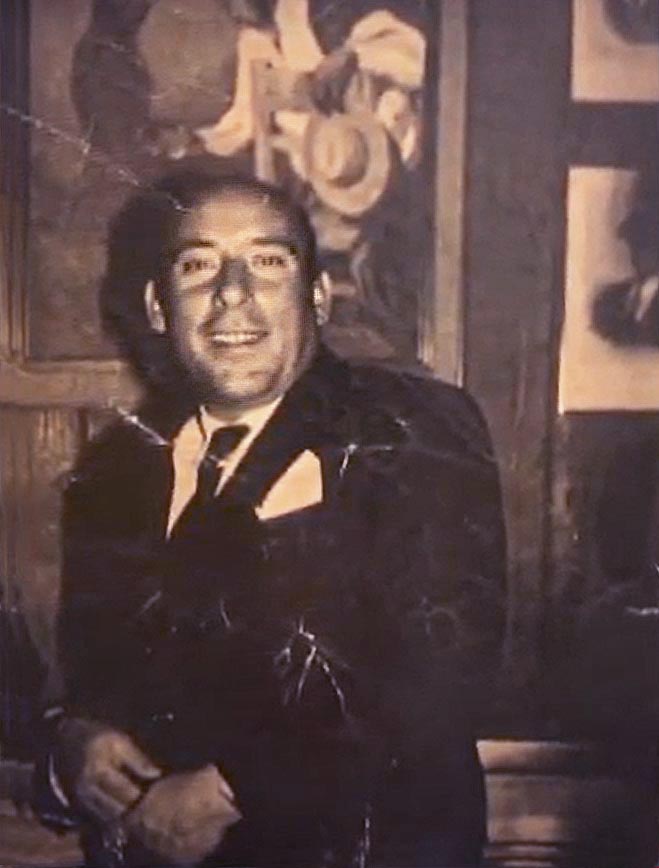

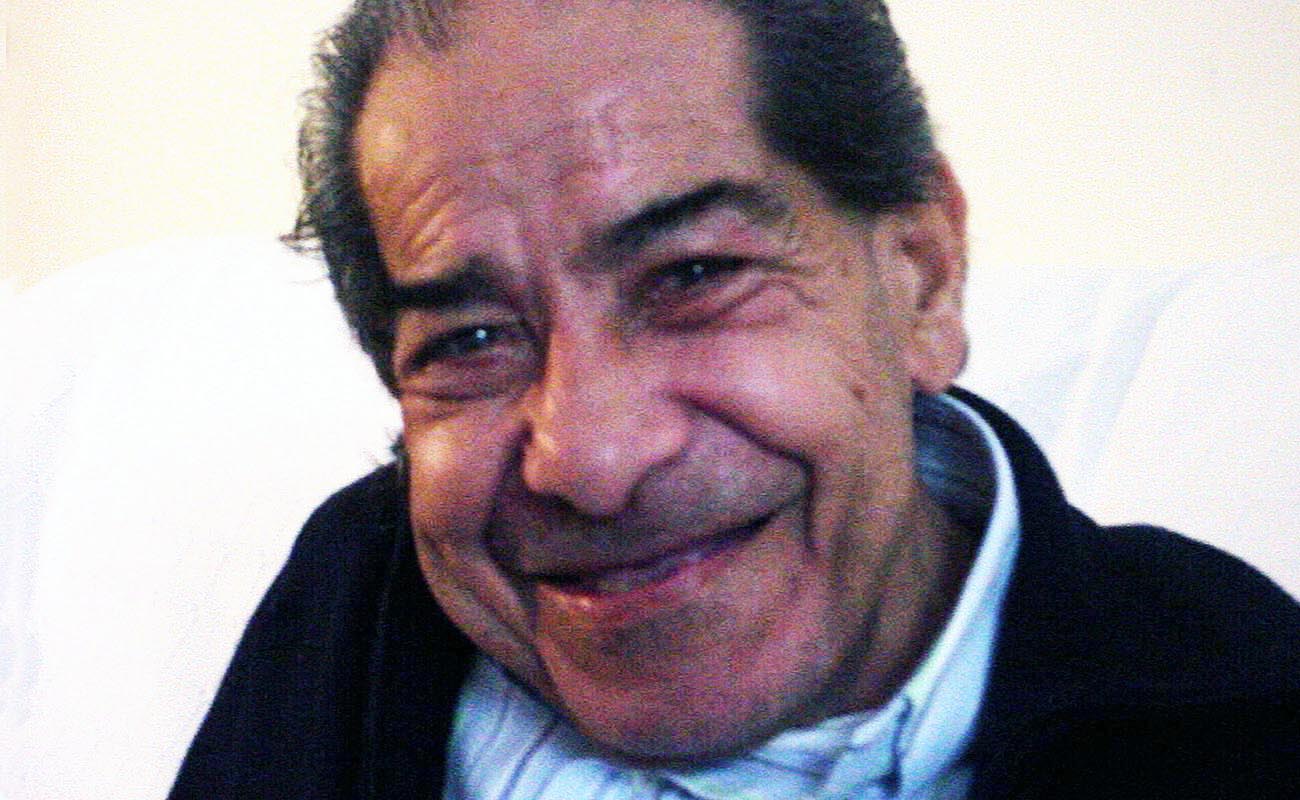

My fascination with the dimension of festive flamenco began to take shape years ago after a flamenco friend of mine saw the famous Bombero routine of Nano de Jerez (Cayetano González Fernandez, 1948), a well-known fiesta shtick with much double entendre revolving around a fireman and his rescue efforts, with a bulerías rhythm drone being the glue that holds it together and keeps the narrative moving along. The routine isn’t Nano’s, although he has become known for it. This surrealistic bit, a chufla in flamenco terms, was actually transmitted from the previous generation via a well-known fiesta artist called el Brillantina, (Manuel Rodríguez del Alba, Chiclana 1920-1970), very popular at the height of the tablao era, and who in turn learned it (“stole it” some would say) from Manuel de Jesulito (Manuel Fernández Cantero, Cádiz, d.1985) according to el Gineto de Cádiz (Juan Jiménez Pérez, 1925-2010) whom I interviewed in 2007.

«The maestro Antonio Mairena, despite his own interest in the most serious forms, and his dignified countenance, was a fine bulerías dancer and singer»

The above-mentioned flamenco friend, deeply attracted to soleá and siguiriya, had virtually no interest in bulerías or other festive forms, and was literally appalled at the Bombero which he considered an “embarrassing insult to flamenco”. Suddenly all his talk of “cante jondo” and “soníos negros” [dark sounds] rang false. Without festive flamenco, without the street humor of the bartender on the corner, or the unmistakeable cheeky behaviour inherited from the historic “majos”, jondo pomp and circumstance is missing its yang. The maestro Antonio Mairena, despite his own interest in the most serious forms, and his dignified countenance, was a fine bulerías dancer and singer. The foot-stomping and grimacing of uninitiated foreigners when they try to evoke flamenco is the result of a long process of being deprived of the surrealistic fiesta face of the art-form, in large part due to Hollywood’s deformation at a time when folkloric bits were the world’s introduction to the genre. Veteran Luisa Triana who is featured dancing in films of the era, explains it was cinematographically expedient to employ flamenco as a melodramatic art of angry sweaty people stomping out their angst, and the rest of the story never got told.

During the twentieth century, this artificial austerity and despair came to be thought of as representing the ever elusive “real flamenco” outsiders dream of being privileged enough to find, even when the quest is as futile as chasing rainbows to find the duende.