The Canastero element in flamenco singing

In 1972 that chorus was like a rallying point for the new flamenco era, complementing the creation of Camarón and Paco

Alborea, ea, ea

tú eres el aire

que a mí me lleva

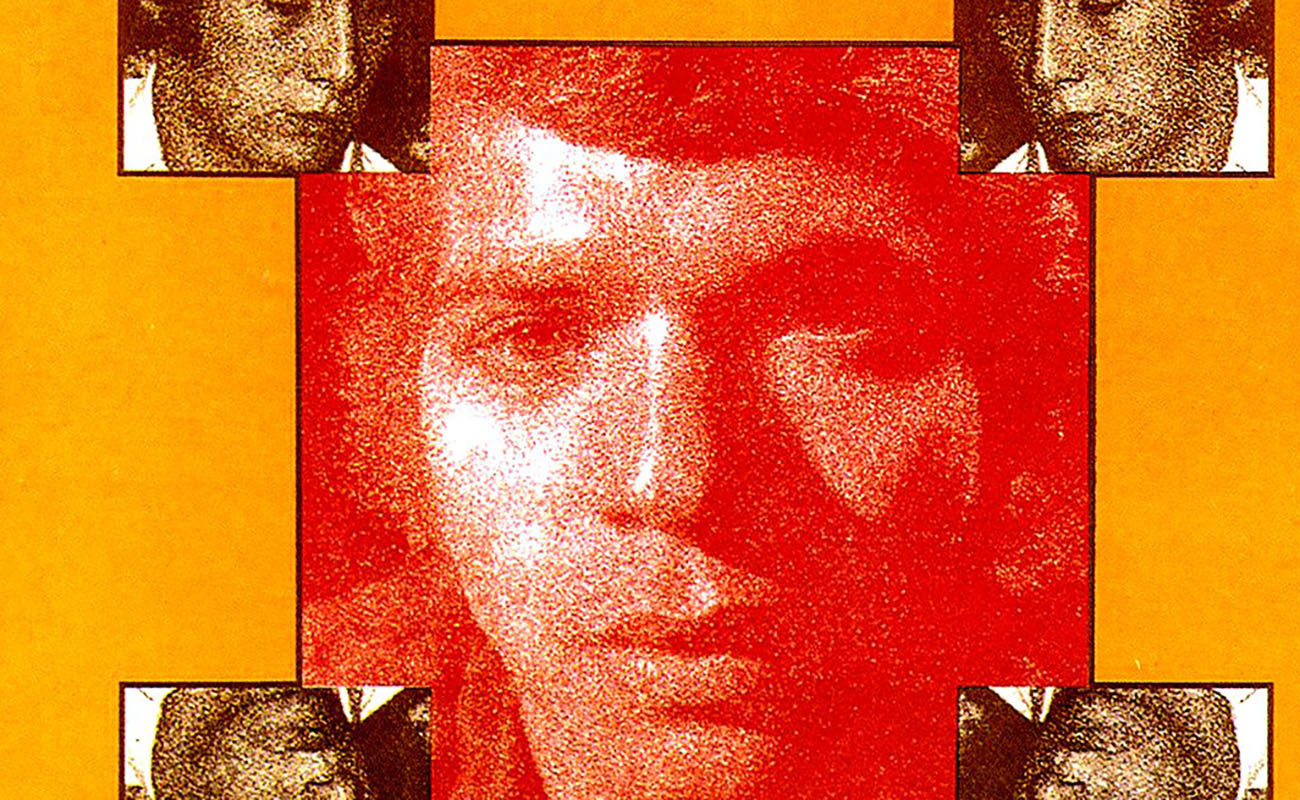

In 1972 that chorus was like a rallying point for the new flamenco era, complementing the creation of Camarón and Paco, “Canastera”, a pseudo fandango de Huelva that wasn’t a fandango at all, more like a tangos feeling overlaying a waltz rhythm. Music. Beautiful music we all embraced despite the myth young aficionados still circulate about the “purists” being outraged. I was living between Madrid and Seville when it came out, and while there was a fleeting moment of surprise, with some people wondering if that recording was even flamenco, acceptance came quickly.

“Al Verte las Flores Lloran”, the first recording of the famous duo, released in 1969, also caused a stir despite its conservative approach and repertoire. The singer’s vocal placement was unlike anything recorded previously, and it was a good sound, full of tender angst that suited flamenco just fine. Not to mention Paco de Lucía’s genius bursting out at the seams at every opportunity. Individually, they were brilliant, together they were hotter than hot giving a much-needed face-lift to flamenco that was in the doldrums.

It was the Canastera recording that caused me to muse that this new singer had to have been listening to the same North African radio stations from across the straight I was able to pick up in Morón much further inland. That bending haunting melodic arc, the unexpected flattened notes that went so well with the cantes de Levante Camarón masterfully interpreted…Antonio Mairena, Caracol, Fernanda and other maestros of the era never sounded anything like that.

The 1969 recording was more conventional, with only tango extremeño to hint at orientalism. Speaking of orientalism, my good friend and flamenco scholar Brook Zern tells how Diego del Gastor once played a falseta for him that had a distinct Arabic twang. When Brook remarked that it sounded Arabic, Diego agreed: “yes…it’s very gypsy”. Take note of Diego’s concept of “Arabic equals gypsy”: the canastero element is part of that sound.

But what does “canastero” actually mean? Aside from the literal translation of “basket-maker”, a traditional occupation of certain groups of gypsies, it has come to mean errant gypsies, as opposed to assimilated ones with a fixed residence.

So, we’re actually looking at the insertion into mainstream flamenco of what was a fairly obscure singing style. It’s extremely rare nowadays to find any flamenco singer immune to that oriental twang popularized by Camarón, and even Spanish pop music has been influenced: Las Grecas, Ketama, Remedios Amaya, Niña Pastori, El Luis, Manzanita, Los Chunguitos, Los Chichos, Triana and many others have sometimes been unkindly referred to as “lolailo singers” because of their fondness for choruses using those syllables. In addition to the unexpected melodies and tones, canastero singing, which is heavy on tangos, also relies on repeated group choruses.

So, should we attribute Camarón for the incorporation of the “canastero” sound in flamenco singing? Yes. While the vocal placement and haunting melodies were there all along, they hadn’t really surfaced in recordings or circulated commercially. This unique style had existed in southern Portugal and neighboring Extremadura for a long time, but until Camarón brought it to the forefront, it was a curiosity, something they did in Extremadura. No canastero-sounding flamenco singing can be detected on the historic anthologies. Camarón’s contact in Madrid with Extremaduran singers Ramón el Portugués, Marelu and Juan Cantero, greatly influenced him, and his innate creativity took care of the rest. Porrinas de Badajoz did a lot to popularize the singing of his hometown, but these tantalizing sounds didn’t find their rightful place in mainstream flamenco singing until Camarón made them so wildly popular we’re still feeling the effects 45 years later.