Tere Peña, flamenco communicator with roots that run deep

María Teresa Peña Fernández, my much-admired friend, Tere Peña, is a flamenco time machine. In 1972 we see her in an episode of Rito y Geografía del Cante (our eternal gratitude to José María Velázquez Gaztelu for the TV series), a timid adolescent observing the family ritual of flamenco singing and guitar as delivered by her mother La Perrata, her

María Teresa Peña Fernández, my much-admired friend, Tere Peña, is a flamenco time machine. In 1972 we see her in an episode of Rito y Geografía del Cante (our eternal gratitude to José María Velázquez Gaztelu for the TV series), a timid adolescent observing the family ritual of flamenco singing and guitar as delivered by her mother La Perrata, her brothers Juan el Lebrijano and Pedro Peña, her uncle Perrate de Utrera and other relatives. She is also the cousin of Inés Bacán, aunt of Dorantes and Pedro María Peña, with many other family ties that make up an authentic flamenco dynasty including connections to Utrera and Jerez, with the epicenter in Lebrija.

A few years afterwards, Tere is the modern radio personality who presents Temple y Pureza, the program that in 2008 earned her the prize for media communication from the Cátedra de Flamencología of Jerez. She also received the Flamenco Hoy prize for 2007, the Latin Grammy in 2002 for her part in the recording of Antonio Núñez “Chocolate”, Communication Prize of Gypsy Culture 2015, two gold records and two platinum ones for Triana Pura among many other rewards and honors. And I won’t continue because the objective is to hear what Tere has to say, an expressive dynamic woman, the perfect representative for this month honoring women.

Tere, you were born right into the heart of flamenco, amidst great artists with a long history, although you didn’t feel compelled to become an interpreter, but rather a producer and communicator. It’s easy to envision you as a flamenco singer, was that option not attractive for you?

My childhood was steeped in music, it was the common denominator. My mother sang beautiful lullabies to me at bedtime, and my brother Juan was nicknamed “Cascabel” (little bells) because he was always happily singing, while Pedro’s guitar was always ready to accompany both of them.

I learned to read music in the nineteen-sixties, and became an avid radio listener. I liked Radio Vida and its music programs that always had the best music of the moment. Later on I became a regular listener of the radio broadcasts of the American military base so I could be right up-to-date. I do like to sing, but only at private get-togethers with family and friends.

Some of the greatest flamenco singers passed through your house…Tio Borrico, Antonio Mairena, Pastora, Caracol… As a teenager were you interested in cante?

My house was like a natural conservatory visited by the greatest flamenco artists, and some lesser ones of contemporary flamenco, as well as journalists and avid fans. My parents were always welcoming and generous, they gave us a continual lesson of “how to be”, offering the best they had so everyone would feel at ease. My brothers and I lived those rich cultural moments full of flavor and knowledge, aware of the privilege we were being offered. It was an invaluable learning experience.

How long were you doing the program Temple y Pureza?

In 1983 I began to work at Radio Lebrija. In ’93 Cadena Ser contracted me to be in charge of the nationally broadcast flamenco program, Temple y Pureza which turned out to be such a satisfying experience. At the same time I worked as producer for several record companies, as well as various platforms for PRISA, such as Canal Plus, the newspaper El País, Localia TV and coordinator for the flamenco record label Palo Nuevo. It was a marvelous experience that allowed me to record historic singers: Bernarda de Utrera, Gaspar de Utrera, Agujetas, Menese, Enrique Soto, Chano Lobato, Fernando de la Morena and El Chocolate for which production I received the prestigious Latin Grammy 2002. I also have wonderful memories of Los Juncales de Jerez where Luis Zambo, Luis de La Pica, Juana la del Pipa, Dieguito del Morao and Tío Paulera, recorded for the first time, while José Vargas El Mono, Tío Enrique Sordera, Manuel Sordera and Tía María Soleá recorded the last. It was a great pleasure to direct this work, so full of pungent memories through and through.

The Lebrija Caracolá festival was your brother Pedro’s brainchild, wasn’t it? What associated memories or anecdotes do you have of it?

Yes, my brother Pedro was the force behind the Caracolá, backed by a group of devoted flamenco followers. Like so many nice stories, it all began at home, and I well remember the many conversations about what they were creating. One anecdote, the snails served in the early years were cooked in a huge bathtub in the patio of my house, and the stage decoration of the first edition was my mom’s nice white sheets. You can see this in photos taken at the time.

And the obligatory question: how do you see the current state of flamenco? Is it on a good path? Do you think people will be singing soleá and siguiriya in the future?

Flamenco has always offered, and will continue to offer numerous paths to develop classic as well as new interpretations. Time will sort out the corresponding success of each proposal. I personally would ask young people starting out to study, not to be in a hurry, not to run some kind of race, not to shout… Moderation.

People rarely sing around the kitchen table any more, but do your people still sing at weddings and baptisms?

Definitely, in my family we take advantage of any pretext that presents itself within the family tradition, the magic of the music as spiritual enrichment that we need to live.

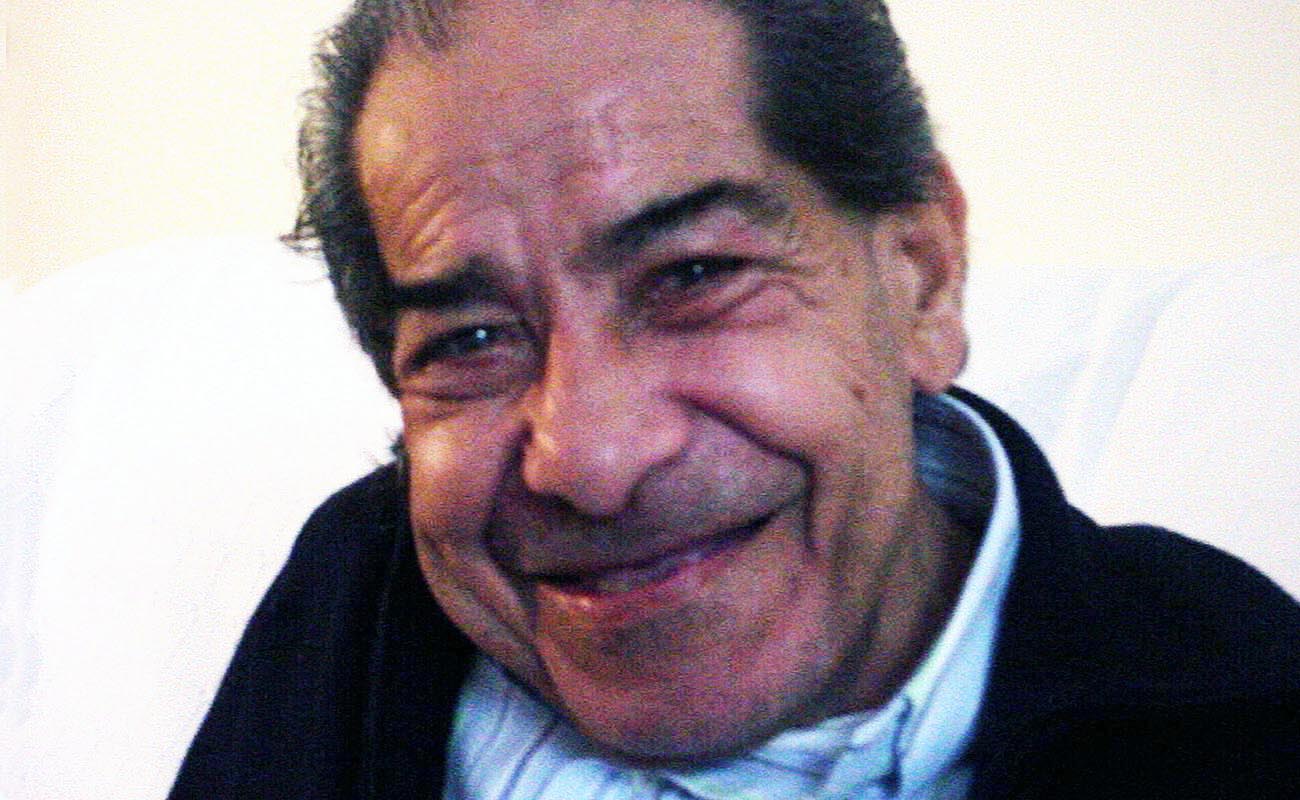

Familia de los Perrate. Rito y geografía del cante. Tere Peña, detrás del Lebrijano. Foto: captura de pantalla