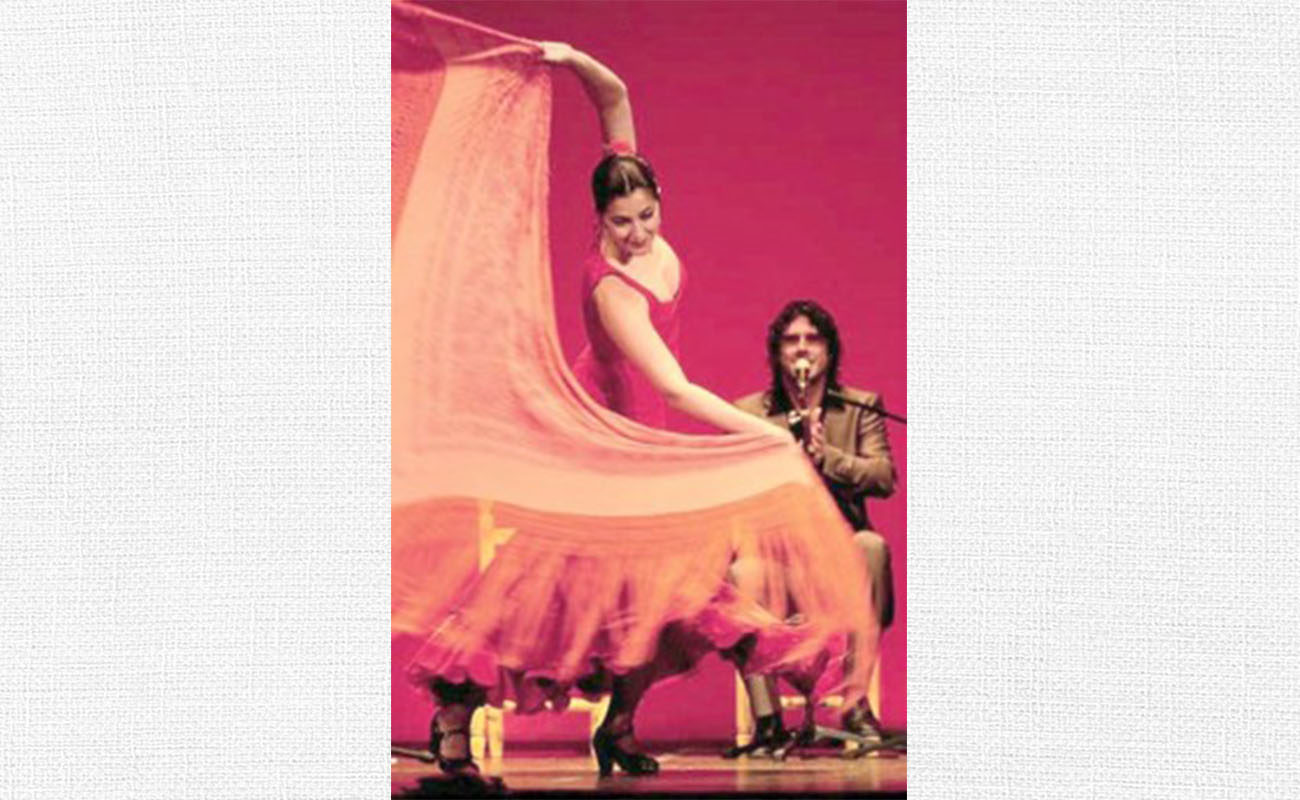

Singing for dance versus singing solo

Now and again you hear the old chestnut that singing for dance spoils the singer for solo performance, “alante”, literally, up front, without dance. But then we’ve got the great maestro Sabicas who said that to become a good solo guitarist, one must first spend 20 years playing for dance, and 20 years playing for singing

José Mercé, Antonio Mairena, David Palomar, Beni de Cádiz, Fernando Terremoto, el Serna, Fosforito, José Valencia, Naranjito de Triana. What do these names of great flamenco singers all have in common? And I could name many more, but the answer is: they all sang for dance before embarking on successful solo careers. Not the occasional guest spot or fiesta finale, but years of dedication to the art of singing “atrás”, upstage of the dancers, in the role of backup singers.

Now and again you hear the old chestnut that singing for dance spoils the singer for solo performance, “alante”, literally, up front, without dance. But then we’ve got the great maestro Sabicas who said that to become a good solo guitarist, one must first spend 20 years playing for dance, and 20 years playing for singing, and although it’s not clear if that’s concurrently, the maestro from Pamplona should certainly know. He played for flamenco singers long before fleeing Spain for the Americas when the Spanish Civil War broke out, and he went on to follow a glorious path alongside the legendary dancer Carmen Amaya, eventually becoming the foremost flamenco guitar soloist. Flamenco expert José Manuel Gamboa theorizes that Carmen’s whip-crack footwork and phenomenal speed pushed Sabicas to the limits, resulting in the guitarist’s famously clean sound and precision.

It doesn’t take much of a leap to apply Sabicas’ wisdom to singers. For many reasons. The most obvious one being that the singer must heed the external rhythm imposed by a dancer and/or singer. When you’re only accountable to yourself, it’s too easy to make allowances and take license, something not to be taken lightly in this art-form so obsessively linked to rhythm.

So, how does singing for a flamenco dancer really differ from solo flamenco singing? An experienced dancer who works inside the box, that is, who follows the unspoken rules by which flamenco artists communicate with each other on stage, won’t be interested in rehearsing with the singer (except for the inspiration it provides): the great Jerez singer Luis el Zambo told me how Farruquito said to him, “you just sing, and I’ll dance”. At most, a dancer might indicate how many verses should be sung, and what sort of ending is preferred.

Take soleá, possibly the most-danced form. A dancer might request one or two verses to serve as introduction before the dance begins, and two or more to be danced, before an ending which might be soleá por buleria or bulería…or something else. Experienced singers have a mental catalog of laid-back styles to prologue, more dramatic ones to build tension, and appropriate endings for whatever form is being danced.

Different forms or palos are sometimes combined, provided they are musically compatible. Taranto is nicely ended with tangos de Granada, a farruca might be wrapped up with tangos del Titi de Triana, since both forms are in the minor key, cantinas leads neatly into bulerías de Cádiz, and so on… This is the kind of specific knowledge that recital singers don’t need to manage. However, both back-up singers and solo singers are expected to sing with artistic sensitivity, good taste and a flamenco feel.

The singer for dance also enjoys greater freedom to explore the possibilities of a cante without the crushing responsibility of holding the spotlight and giving an impeccable performance. The weight of that kind of perfection can lead to solo singers occasionally having a cold delivery with little risk-taking. In this sense, a back-up singer has plenty of opportunity to develop a personal style or creative variations on classic forms, because the dancer provides a virtual safety-net the soloist doesn’t enjoy.

By no means can a back-up singer be considered a lesser interpreter, and in fact, those who avoid singing for dance, will always be lacking that essential experience. Singers for dance adapt to solo singing with relative ease. Soloists however, have a lot of catching up to do before singing for a dancer.