Paco de Lucía y familia: El plan maestro

In a few months, in February of 2024, it will have been a decade since a legendary flamenco guitarist, admired by musicians the world over, took his leave. Francisco Sánchez Gómez, a common name for an extraordinary person, our beloved Paco de Lucía.

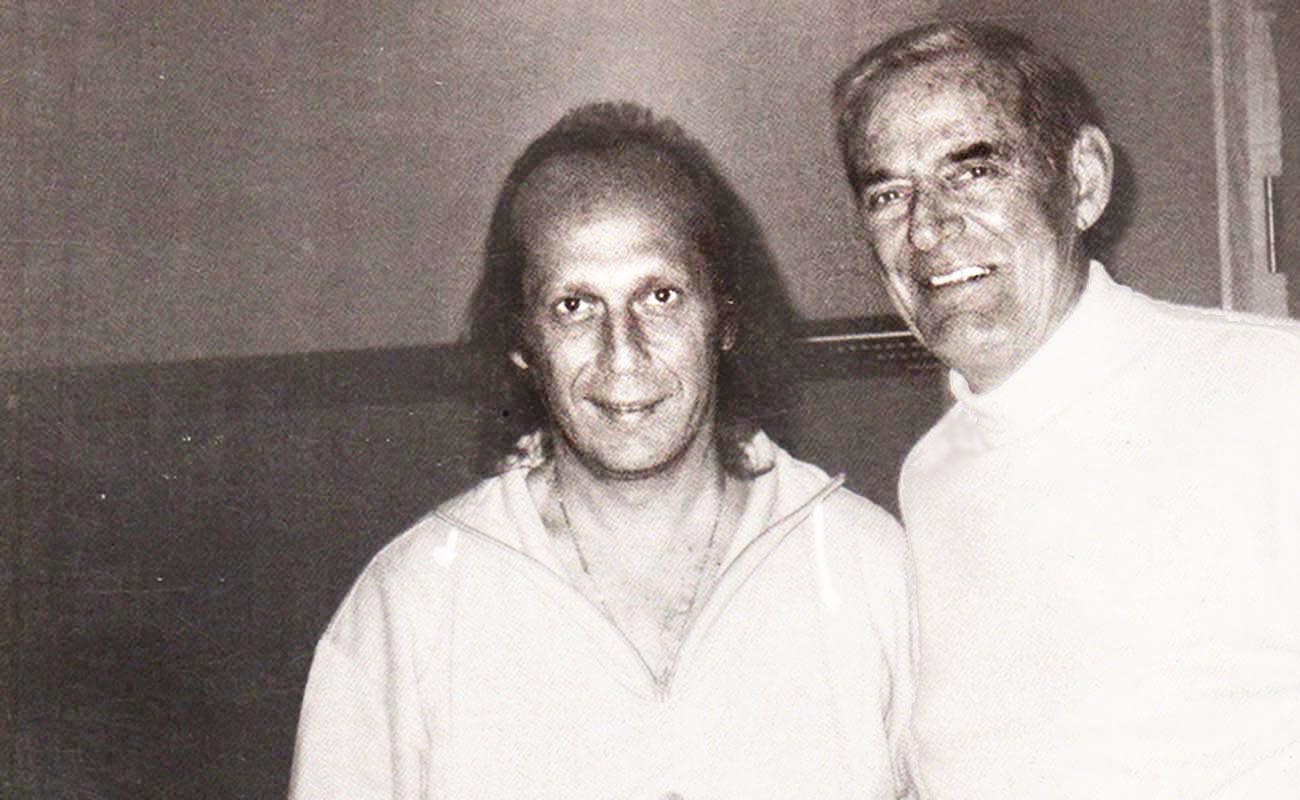

In a few months, in February of 2024, it will have been a decade since a legendary flamenco guitarist, admired by musicians the world over, took his leave. Francisco Sánchez Gómez, a common name for an extraordinary person, our beloved Paco de Lucía. At only 66 the king of guitar and idol of guitarists, the one who redefined the genre, unexpectedly spread his wings, flew away with his music, and flamenco wept. The musicians of the world and lovers of culture wept. And I also wept, consoled in that moment by my friend José Manuel Gamboa when the news arrived during the Festival de Jerez. I had met Paco in New York when we were both teenagers at Mario Escudero’s studio where I was studying with Mario. Paco, his protégé, came to the studio regularly to meet with Mario, who introduced him to the New York flamenco community of that time and expanded Paco’s knowledge of the art-form. It was a fruitful connection for both.

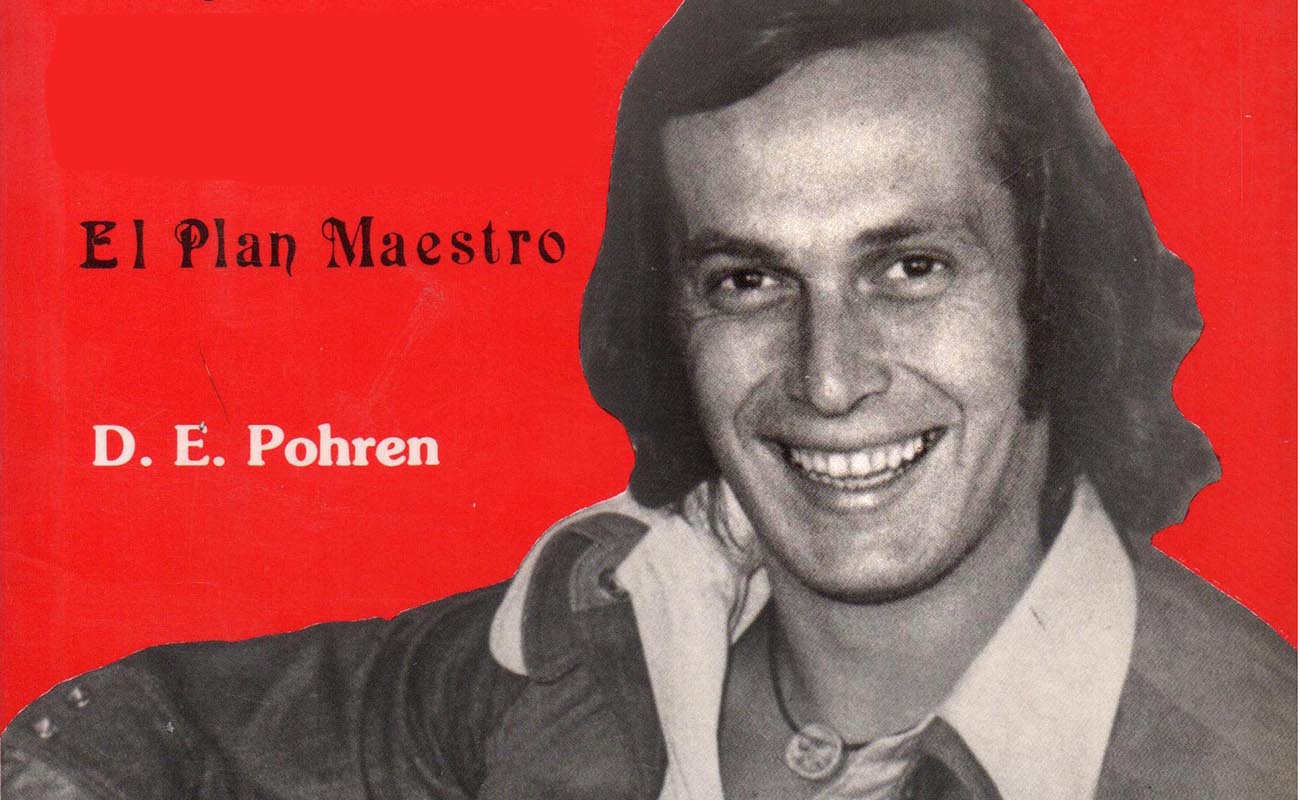

In 1992, when Paco was riding the crest of his fame, an American writer, guitarist and entrepreneur Don (or Donn) Pohren (1929, USA – 2007, Madrid), wrote his biography: Paco de Lucía y familia: El plan maestro. Years earlier, in 1962, Pohren had already published The Art of Flamenco, a book that explained the fundamentals of flamenco. It was translated from English into Spanish, French, and Japanese, fostering a keen interest in the person and guitar playing of Diego del Gastor from Morón de la Frontera, who was being promoted by Pohren.

So, there arises the curiosity that, on the one hand, Pohren painted the image and character of Diego del Gastor, a guitarist far removed from modern influences, steeped in the flamenco of the past. On the other hand, with this book about Paco, he took us on a journey straight to the most groundbreaking guitarist of the same era, the musician who designed contemporary flamenco history, thus altering the course of the genre. Pohren predicts “Even as these words reach the reader” the evolution/revolution will be in high gear. Little could he imagine those words would still be pertinent in 2023 as I write these sentences.

The backdrop that Pohren describes is steeped in the poverty of the time, the hardship imposed on Paco’s father by his way of life, the sacrifice of playing at private parties for a pittance before the Civil War, or afterward, during Paco de Lucía’s childhood. Between one thing and another, the biography of the Sánchez Pecino family is an X-ray of the development of flamenco in the second half of the 20th century. Pohren highlights the contrast with the present saying, ‘When Antonio Sánchez Pecino (Paco’s father) began in flamenco, Manuel Torre was still riding a donkey to the gatherings.’

Pohren describes the life and goals of the father of five children who struggled to support his family. Day in and day out there were parties with Antonio el Chaqueta (singer), Chaleco (dancer), Antonio el Flecha, Jarrito (singers), el Brillantina (festero), or Paco Laberinto (dancer), among others, paying 5 pesetas to the guitarist, which was twice what the laborers in the fields earned.

There were gatherings in Seville with Ricardo, Melchor, or Manolo de Huelva, among others, that would leave their mark on the playing style of Paco’s father, which he later passed on to our Paco. These experiences were intertwined with the precarious life of the parties thrown by wealthy gentlemen. Paco became an encyclopedia of classic flamenco singing, and his fame only continued to grow.

Paco’s first recording was with his brother Pepe, Los Chiquitos de Algeciras, in 1962, the same year as the famous competition in Jerez in which both brothers, aged 16 and 14, won prizes. Ramón, the elder brother, had a dignified but slower evolution, while Paco and Pepe were on an express route to fame.

Paco always missed having had a formal musical education, but had a well-developed concept of what good flamenco is and is not. The formation of his sextet was the beginning of a new era. I remember that I couldn’t understand how some of his musicians had non-Spanish names.

Pohren provides a concise analysis of Paco’s recordings that helps us observe his creative evolution and the transition from Ricardo to Sabicas as a focal point of his admiration. An anecdote Jerez singer Domingo Alvarado shared documents the moment of this transition. He recounted that young Paco, after meeting Sabicas and seeing him play up close, was impressed by the maestro’s clean sound and couldn’t stop repeating in amazement, “He doesn’t miss a single note…not one!”

A kind of bonus track, Entre dos aguas from the album Fuente y Caudal (1973), would ultimately place Paco de Lucía in a privileged position in the history of music. Despite his innovation, he was a purist in his own way. He would say, “Excessive sentimental attachments to the past can stifle growth.” He also believed that many young people lacked deep knowledge of the roots. Let us conclude then with his wise advice that continues to be relevant for the new generation: “The secret lies in the singing.”

Dear readers, this simple article is not intended for promotional purposes, and I don’t believe the book in question is available for sale in bookstores. It’s possible it may be found on collector’s websites or historical resources like Internet Archive. I simply recommend it as a resource for better understanding one of Spain’s greatest musicians.

Loretta Magiar 27 October, 2023

I’ve always loved and admire Paco. De Lucia I also cried when he passed away we’ve lost a great one. It doesn’t matter that he wants informal educated in music. He played from his soul and that’s more important.