María Jiménez, icon of popular flamenco

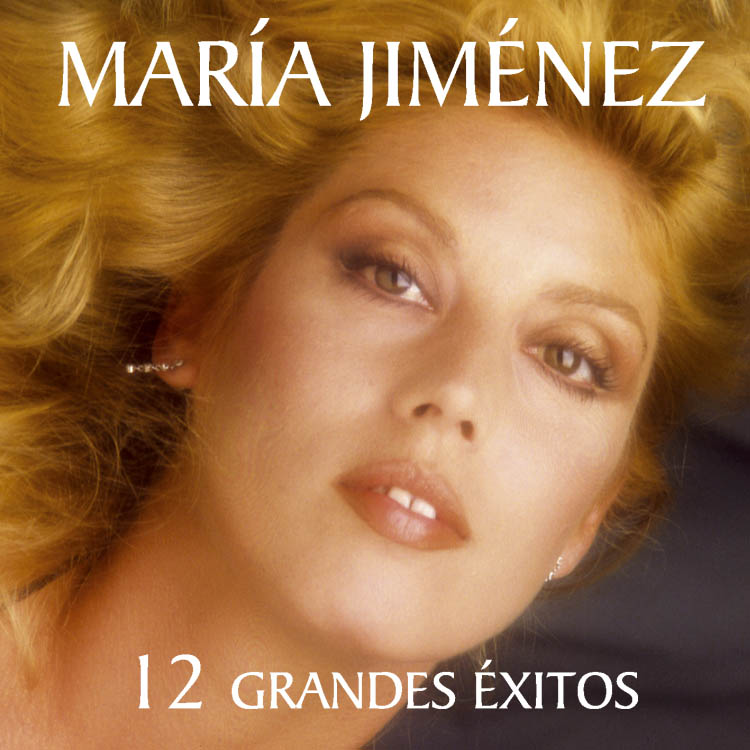

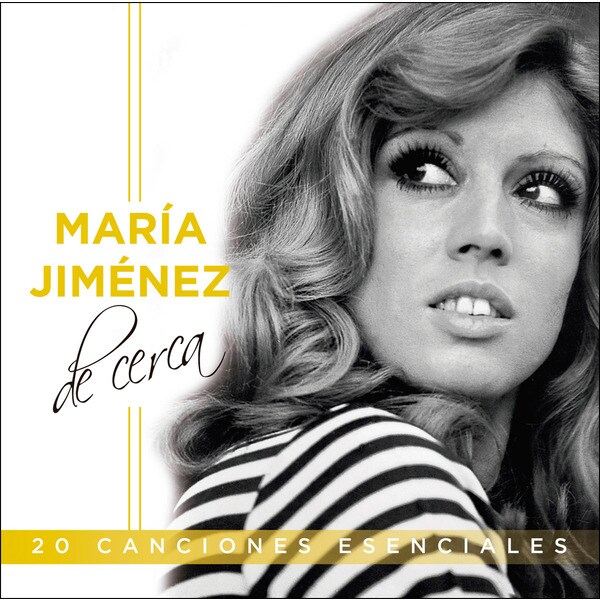

In the middle of it all was María Jiménez, seducing audiences with her brash youth, blond hair and gossip-worthy adventures. She was our Andalusian Marilyn Monroe.

The Potaje Gitano de Utrera is a rite of early summer that has been a part of most of my adult life. In the festival heyday, flamenco was primarily a summertime event, and there was no Youtube to fill in the gaps if you missed the major events.

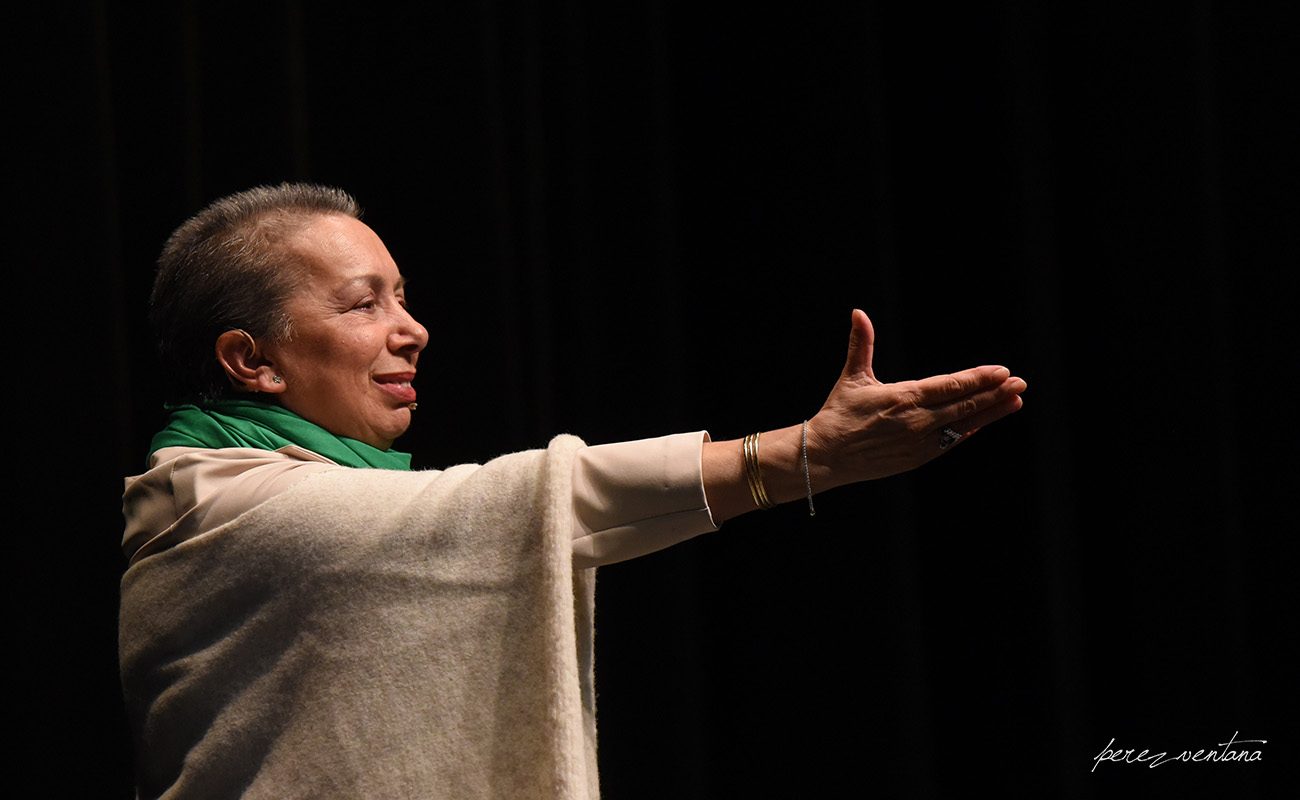

This year’s 66th edition of flamenco’s pioneering festival was dedicated to María Jiménez, a sort of lifetime achievement award for individuals whose career has developed alongside flamenco. A tsunami of memories flooded my mind when this major figure of pop flamenco of the 1970s appeared on the athletic field of the Colegio de los Salesianos – so many people rushed to greet her, I was lucky to get a brief glimpse of the legendary singer. Now physically diminished, but still bubbly and charming, she was clearly delighted by all the attention.

María Jiménez, from Triana, created her own musical niche: breathy ballads, often to slow bulerías, a sound she helped popularize with songs of Paco Cepero and others who composed for her, as well as rumbas that might be soft and sweet, or punchy and aggressive. Her apex was the nineteen-seventies and early eighties, bringing a new aroma to popular flamenco also cultivated by other beautiful women like la Susi, Remedios Amaya, Niña Pastori and Laventa among others, featuring slick contemporary arrangements.

In hindsight all the pieces slide neatly into place. In the beginning of the modern era, God created Camarón. Then came Las Grecas, who expanded our musical taste and vocabulary with non-words like “locamenti”, Lole and Manuel’s dreamy flower talk, and the whole flamenco rock movement that followed. And in the middle of it all was María Jiménez, seducing audiences with her brash youth, blond hair and gossip-worthy adventures. She was our Andalusian Marilyn Monroe.

My regular visits to the record department of the Corte Inglés in Seville’s Plaza del Duque were no longer limited to straight-ahead cante. Now “outsiders” like Alameda, Triana, Pata Negra and so many other groups were playing in the same sandbox, demanding a niche. That was back when people made recordings, not for promotion, but to generate income. It was a treat to be able to listen to records at the store, mostly cassettes in those days, and you could slip over to the photocopy area to copy liner notes which nearly always included the verses.

I first saw María Jiménez around 1972 when she was billed as La Pipa, a featured artist at Los Gallos tablao in Sevilla. Despite the distinctly slick sound, María Jiménez belonged, and continues to belong to flamenco. It’s not straight-ahead flamenco, but she never strays far, and her repertoire and delivery are Andalusian, music to be enjoyed when you need a rest from Talega or Periñaca. Her close friendship with Bambino was well-known, and she appeared regularly in magazines and on television. María was originally groomed to be the female answer to Bambino, but her own combustible personality took her way beyond that.

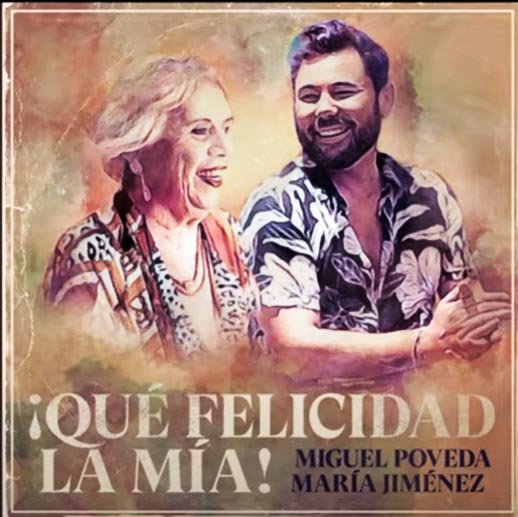

María Jiménez’ greatest hits, Se Acabó, En la Oscuridad, Con Golpes de Pecho and Sensación among others, identify those exciting times when derivative flamenco began an evolutionary process that continues to this day escorting us into the future. A delightful collaboration with Miguel Poveda, ¡Qué Felicidad La Mía! (30 Años En La Música), recorded in 2019, is a celebration of those times, of María’s cheeky charisma and of her exuberance.