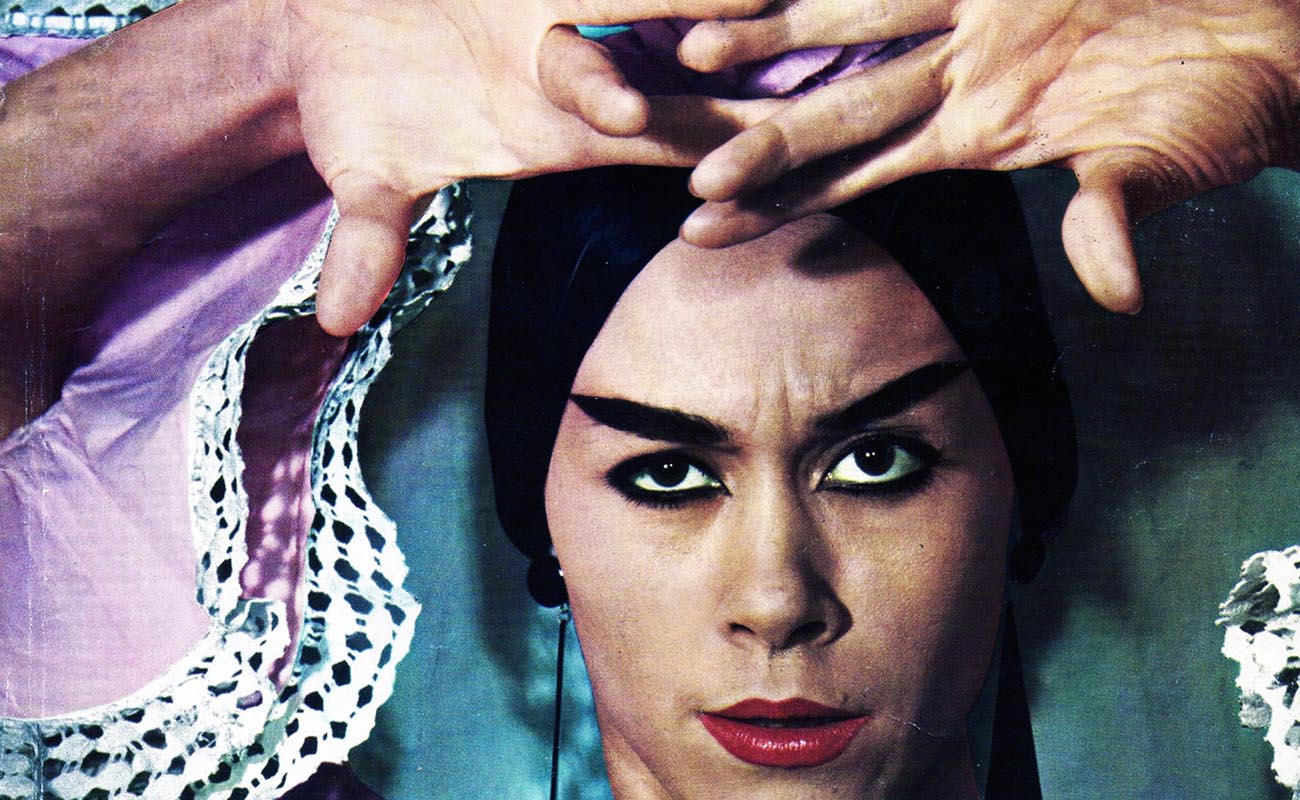

Manuela Vargas at The New York World’s Fair

Flamenco was the main attraction, and people put up with long lines to enter the auditorium where Manuela Vargas (Seville 1941), the beautiful, amazing, gifted Manuela Vargas and her outstanding group performed daily.

In 1964, when Spain was still pulling itself out of the depths of postwar poverty, the powers that be decided to invest a great deal of money to mount one of the most extravagantly beautiful pavilions of the New York World’s Fair as part of an aggressive campaign to attract tourism from abroad with the slogan “Spain is different”. Having a season pass, I was at the pavilion nearly every day. In the garden leading to the entrance there were colorful groups who performed typical Spanish folk dances, but without any doubt, flamenco was the main attraction, and people put up with long lines to enter the auditorium where Manuela Vargas (Seville 1941), the beautiful, amazing, gifted Manuela Vargas and her outstanding group performed daily.

At that time, flamenco was struggling to find a viable future. The early tablaos – Corral de la Morería, Café de Chinitas, Zambra, Los Canasteros, Las Brujas and others – fashioned after the earlier cafés cantantes, catered to foreign visitors’ curiosity about the exotic art-form, and general interest shifted from flamenco singing for Spaniards to flamenco dance for foreigners. Sangría and paella, pretty girls in ruffled dresses and swarthy men with dark looks made an irresistible formula. It’s unfortunate flamenco of the era has suffered such bad press, even to the point that some people today still relate flamenco dancers to prostitution.

Manuela Vargas is mostly remembered for her 1984 performance in Medea with the music of Manolo Sanlúcar, but without a doubt, years earlier, at the New York World’s Fair, she laid out new forms that have enriched flamenco dance in important ways. Although considered an interpreter of the Seville school as received from Enrique el Cojo and Matilde Coral, I now look back at the dancer who presented four shows daily in the auditorium of the Spanish pavilion, and remember a personality so original and intense, it seems impossible Manuela Vargas, the great creator, was so unfairly pigeon-holed.

First of all, the repertoire. For decades, Spanish dance companies such as those of Antonio el Bailarín, Pilar López, Ximénez Vargas and José Greco among others, as well as that of Carmen Amaya whom we had lost only a short time before Manuela performed at the Fair, all of them felt the need to include “danza”, folkloric pieces, semi-classical it was known at the time…Boda de Luis Alonso, Goyescas, Amor Brujo, jota, bolero school and other odds and ends from Spain’s rich cultural heritage. It made a fine show, but Manuela Vargas had other ideas. Her contained but intensely temperamental style was best-suited to flamenco, and that’s what she unapologetically presented.

Contrary to official accounts which describe a program I did not see, the shows at the Spanish pavilion were monothematic. One was based on soleá, caña, romance and related items, while another was devoted to the cantiña family…alegrías de Cádiz, mirabrás, caracoles, romeras, another to tangos, and so on. In one of the shows, the main number was petenera, beginning with Pastora Pavón’s and Niño Medina’s free-form version. Veteran dancer Luisa Triana (Seville 1932) believes that may have been the first time a free-form flamenco style lacking a steady beat was danced in any credible way.

Manuela’s flamenco dance wardrobe set the style for years to come. Rather than the popular knee-length dresses of the era, she chose the more elegant floor-length ruffles that began at the knee, a flattering look for Manuela Vargas’ slim line. Impossibly voluminous ruffles at the shoulder contrasted in a quirky way with her sedate style that almost seemed symbolic of how she applied a patina of the past to her personal vision of the future. Her dresses with train, batas de cola, were the longest I’d ever seen, and I still remember the crunchy sound of a long white bata de cola as Manuela appeared from the wings illuminated by black-light.

Manuela Vargas chose her back-up carefully, and surrounded herself with the best artists of the era, at the Fair and elsewhere: Fosforito, Naranjito de Triana, El Güito, Fernanda y Bernarda de Utrera, Beni de Cádiz, Juan Habichuela, José Cala El Poeta among many others, and with their input, developed dance forms for tientos, caña, mirabrás and taranto that are still referential today.

After one performance I felt brave enough to visit the dressing-room to ask her to sign my program. However, there was such a crowd of people, I gave up trying and approached a young dancer from the company to sign it for me. Not until more than 50 years later did I read the scribbled signature: Cristina Hoyos.