Flamenco… parental supervision advised?

Surely, people from other countries and cultures deserve an accurate representation of flamenco, that peculiar intensity we long for, and whose pungent aroma is as irresistible as that of a Jerez winery.

Some years ago on an internet travel forum I was following, a man wrote saying he was about to visit Spain with his family, and asked for someone to recommend a flamenco show “suitable for minors”. If you don’t see the humor immediately, just give it a few seconds to sink in.

Or maybe that person was on to something. Travel writer Rick Steves included the following observation in a review in Newsday magazine of a flamenco show he’d seen: “Youngsters in the audience found the dancer’s contorted face, demonic expression and outstretched arms terrifying”. Yikes! What is it about flamenco that makes it so susceptible to hyperbole?

Ask the average man-in-the-street to strike a flamenco pose. He will quickly knot up his face with an angry grimace, and stomp the ground repeatedly. If it’s a woman, she’ll slither into seductive mode, hike up her skirt, maybe even blow air kisses. Does this embarrassing tableaux correspond in any way to the personality of flamenco as understood by serious followers of the art-form?

If your answer is “no”, or you think it’s merely humorous, read on…

To check the pulse of theater-goers’ reactions to flamenco shows, over the years I’ve collected comments made by professional reviewers, often dance authorities, of the most important flamenco performances abroad. This is more than a hobby. The foreign perspective is important because in the end, the theaters and festivals of other countries are the biggest consumers of large format flamenco shows, and the taste of those audiences ends up setting the direction of flamenco in general.

Jeffrey Taylor of the British publication The Guardian wrote about London’s Flamenco Festival some years ago: “The popular perception of flamenco is a mating game around a flickering campfire, reeking of rebellion and oozing sex.” Incredible though it seems, we still have to deal with the myth of women in flamenco being “for sale”. You sometimes even hear that a tablao is a brothel with live music.

Another British magazine, the Daily Star, brings us Christine Lahoud who, speaking of the same festival, kindly informs readers that “the power of flamenco lies in its stomping. This characteristic pounding is the most important element.” (I had no idea!)

It gets stranger. Writer Manny González once pointed out in the Philippine Sun Star: “Flamenco is a song-and-dance by gypsies who go around stomping on the floor as if they were trying to get the lease broken”. Humorous, in an offensive sort of way.

The recent closing of historic flamenco clubs (tablaos) in Madrid is attributed in large part to international travel restrictions currently in effect, and people’s reluctance to venture far from home in an uncertain scary world. Without “guiris”, the derogative term for non-Spaniards, the tablao business quickly dried up, eventually followed by other small venues. For this reason, it behooves us to identify, define and hopefully fine-tune the sometimes skewed concept of flamenco held by international and Spanish audiences alike.

Not even the orchestra director, maestro Leopold Stowkowski, could resist gushing folderal. After seeing Carmen Amaya dance in New York, the Herald Tribune quoted him as saying “she has the devil in her body!”

Veteran dancer Luisa Triana, daughter of Antonio Triana who partnered and choreographed Carmen Amaya for many years, performed dance segments in various Hollywood movies. She recalls how directors would always instruct her to dance faster and pound the floor harder, “because that’s what people like”. Those same directors wanted nothing to do with singers…after all, who could stand what British theater and dance critic Paul Taylor has ridiculed as “muezzin-like wailing” and ”over-pitched melodramatic acting”? To this day, many non-Spaniards don’t realize that flamenco, in addition to guitar and dance, has associated vocals.

In an interview fifty years ago, our favorite flamenco genius gave his opinion of misguided impressions when he referred to “those flamencologists who only see the fantasy of the moon, of the gypsy, of the olive trees: in other words, García Lorca. That’s not the reality of flamenco”. Paco de Lucía, Triunfo magazine, April 10, 1971.

Surely, people from other countries and cultures deserve an accurate representation of flamenco, that peculiar intensity we long for, and whose pungent aroma is as irresistible as that of a Jerez winery.

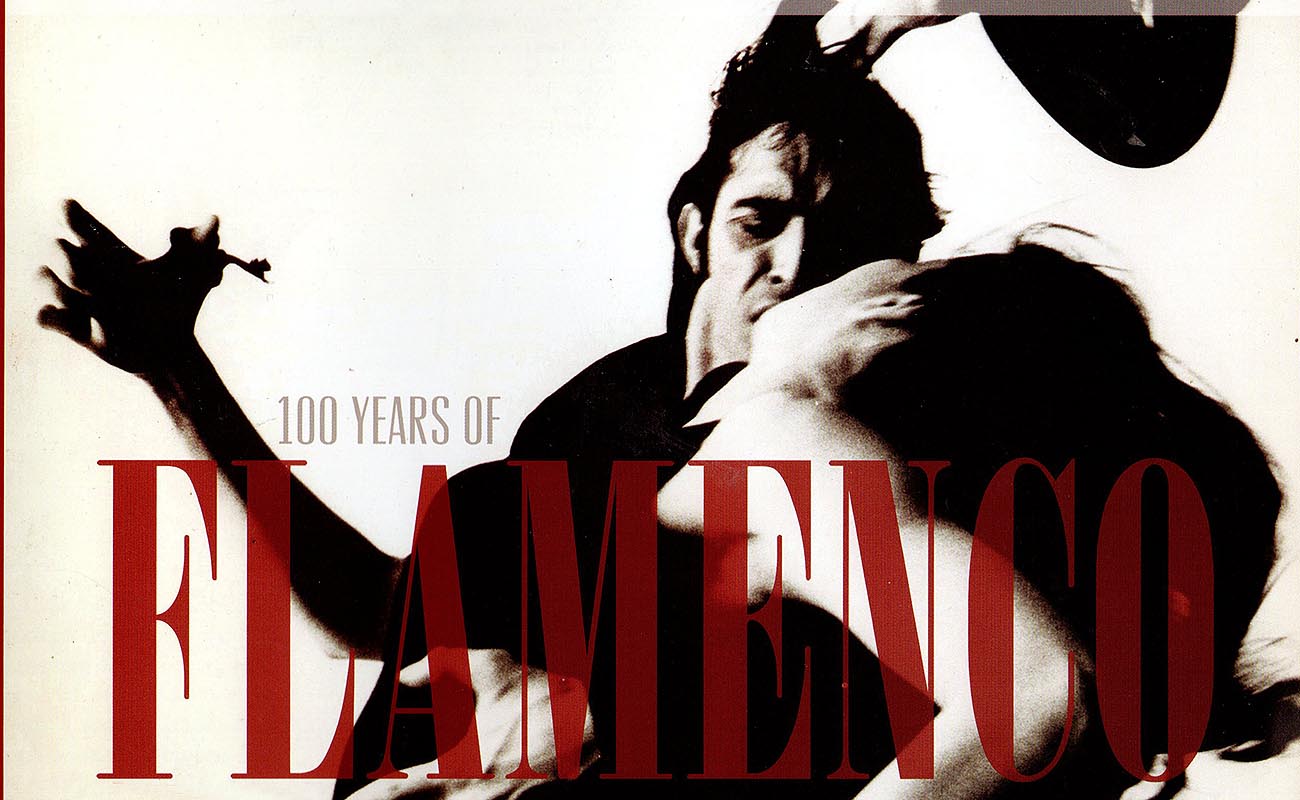

Image: Ramón de los Reyes and María Alba – Cover of the catalogue “100 years of flamenco in New York”.