Feathers, ‘vedettes’ and flamenco

All that was more than 40 years ago when today’s most renowned flamenco artists were just being born, and the art-form was defining its identity as an Intangible World Cultural Heritage.

The vibrant café cantante period of rowdy music halls that featured a variety of acts in addition to flamenco, ran out of steam well before Spain’s civil war. After the conflict ended in 1939, many performers survived the terrible lingering poverty by working with itinerant variety shows. Few homes, especially in smaller towns, had a television set until the late nineteen-seventies so entertainment beyond radio meant a live show, which in turn meant theaters. And since many towns could not afford to have a theater, itinerant companies scratched out a very modest living at the expense of much car travel, third-rate lodging and hastily-prepared shows for presentation in community centers, school patios and other makeshift locations.

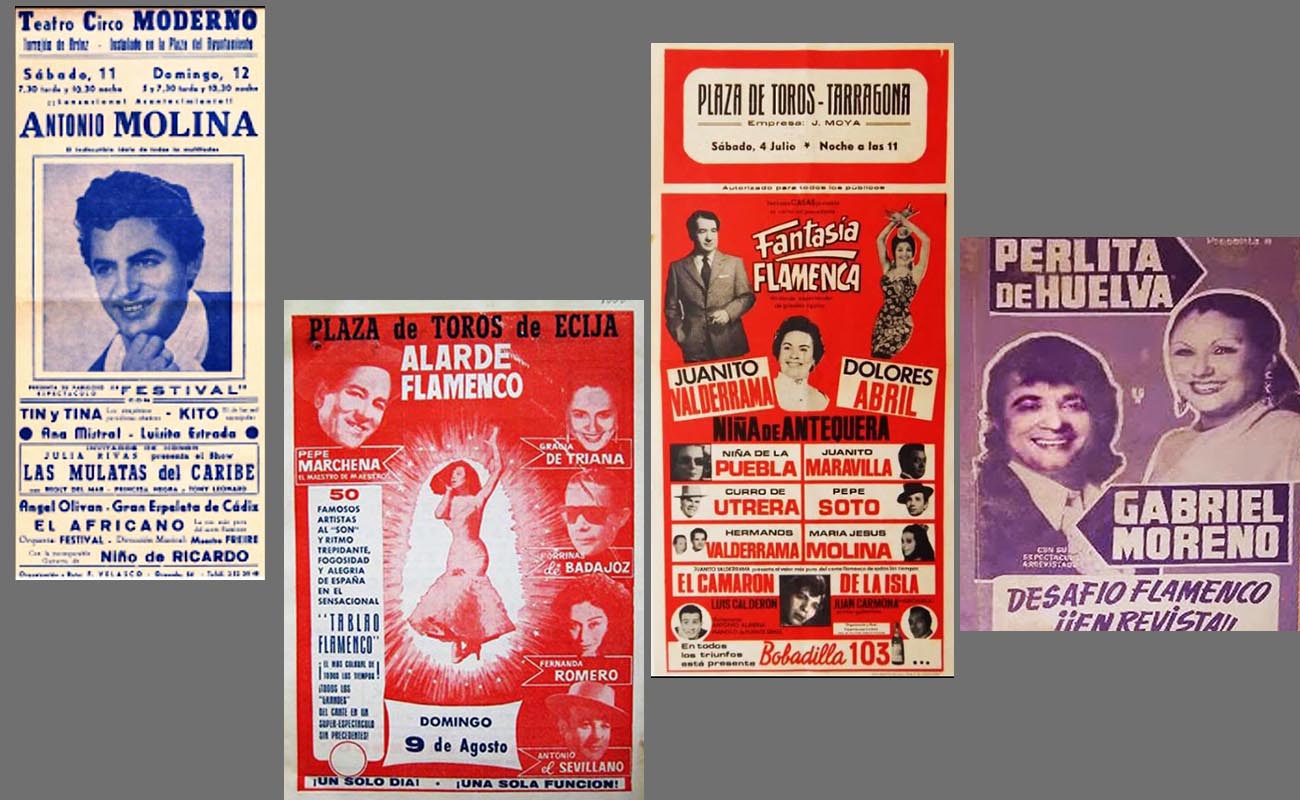

With the disappearance of Franco and censorship, came the “destape” fever, the peeling off of clothing by women at the slightest provocation in frivolous suggestive films and musical variety shows that flooded the market with a new mildly risqué type of entertainment that featured flamenco artists alongside “vedettes”, beautiful females who sang and danced in sequins and feathers. If you look closely at the posters at the head of this article, in addition to prominent names of the era such as Niño Ricardo, Curro de Utrera, Porrinas de Badajoz, Juanito Valderrama, Juan Habichuela, Pepe Marchena, Gabriel Moreno, Niña de La Puebla, Fernanda Romero and Espeleta de Cádiz among others, you’ll see Juanito Valderrama presents Camarón de la Isla as “el valor más puro del cante flamenco de todos los tiempos” (the purest talent of flamenco singing of all time), words that show the extent of the young singer’s popularity from early on.

Working this same circuit were vibrant artists such as Enrique Montoya, Amina, La Pelúa, Faico, El Chino de Málaga, and sevillanas groups such as los Romeros de La Puebla among many others. I feel fortunate to have caught the tail-end of the itinerant musical reviews with vedettes and flamenco. “Fortunate”, because despite the rustic conditions and low salaries, it was flamenco history about to disappear, a way of working that’s hard to imagine in the modern era of classy theaters and comfortable dressing-rooms with all the amenities.

The company I toured with starred a middle-aged vedette, Pilarín Cuevas, and in addition to our small flamenco group, included a singing duo, the Hermanas Lima, a crooner from Almería, Manolo Campos and la Portuguesiña, a go-go dancer who bopped around in a bikini to a recording of “Daddy Cool”. There was also a comedian and showman whose name I don’t remember. Other companies of the era would sometimes have an acrobat, a juggler or a magician. The brief flamenco portion was an opening crowd-warmer: fandangos de Huelva, alegrías and rumba to end (bulerías had not yet assumed dominance).

We set out from Madrid one morning, a caravan of four vehicles, after picking up several large boxes of curtains to be hung at each venue, and a supply of Marlboro cartons that would be raffled at each performance in the intermission. Upon arriving in a town, a loudspeaker was mounted on the roof of the head vehicle, and we drove slowly around announcing the show in typically hyperbolic language, “internationally famous” and all that.

After touring the area northwest of Madrid, including several days at La Tartana nightclub in Salamanca, we headed for Extremadura, towns so small, not one street was paved. In one such town the municipal authorities had set up a makeshift “theater” in a large barn. A couple of confused pigs were escorted to another area, but someone had to remove the straw that covered the floor. Everyone in the company was given a pitchfork to clear space for “seating” – everyone but the guitarists that is, who refused to help alleging the need to protect their hands. People would be bringing their own folding chairs and crates to sit on. There was no running water, so we moistened our make-up sponges in leftover Coca Cola.

Not all the venues were so primitive however. Other places I remember are a nightclub called Fokker in Jaraiz de la Vera, a community center in Guadalupe and the Lope de Vega theater of Chinchón on the return trip. At the Fokker, a man appeared before show-time who said he represented the syndicate of performing artists. He handed me a form and said to write down the titles of each piece of music and the names of the composers, even though I told him flamenco had no composers in the conventional sense. I remember first writing “alegrías”, and the guy said to put the composer’s full name and phone number, so I put “Enrique Mellizo”, made up a phone number with a Cadiz area code and filled out the rest of the form with fanciful names and numbers.

All that was more than 40 years ago when today’s most renowned flamenco artists were just being born, and the art-form was defining its identity as an Intangible World Cultural Heritage.