Cuplé… hotline to flamenco

The most flamenco cuplés present as bulerías rather than “songs accompanied por bulerías”. Creative interpreters move through the possibilities in search of the hotline to the jondo. And that’s where the magic happens.

Ok, so what exactly is cuplé? Decades ago, when the first popular songs were cleverly woven into bulerías, at a time when the latter was still in its formative stage, it would usually be music and lyrics borrowed from Hispanic sources, folklore, zarzuela (light opera), ballads, etc., passed through the prism of a bulerías beat, that great invention that has the potential to accommodate any kind of music, poetry or emotion, to be repurposed as flamenco.

Bulerías gets some bad press – the great maestro Antonio Núñez “Chocolate” dismissed it as “cante de bulla” (low-class and rowdy) – but it cannot be considered a lesser form of flamenco. It’s not a cheap thrill nor a light divertimento destined to fill in time between other more noble forms. It’s essential and vibrant, and in the hands and voices of great singers who dominate the form, bulerías cuplé can ascend to a high level. There are relatively few specifically associated styles of bulerías, probably no more than ten percent of what gets recorded. The other 90% includes, not only cuplé, but whatever a singer comes up with at any given moment.

Adela La Chaqueta.

The word “cuplé” comes from the French “couplet”, which, in turn, derives from Latin, “copulare” (no giggling please), and which came to be applied to this alternative to bulería corta. Which requires another definition: what is bulería corta? Let’s just say it’s the alter ego of soleá, verses of 3 or 4 lines in the Phrygian mode (flamenco mode), that may or may not include the repetition of lines. Nearly everything else inserted into bulerías, tends to be called “cuplé”.

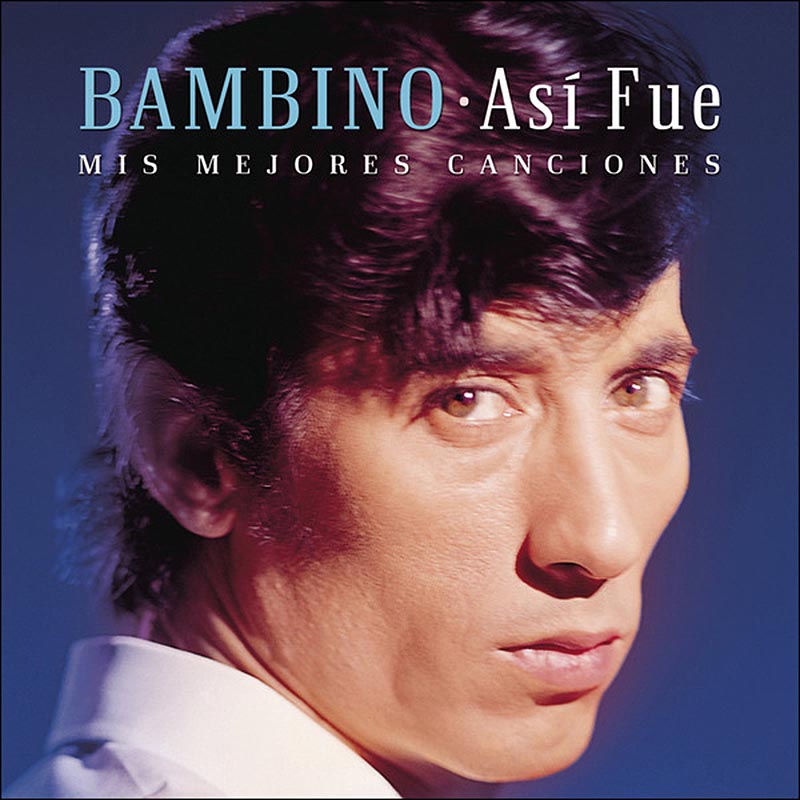

There have been many hundreds of cuplés por bulerías recorded by well-known singers, who, in the best interpretations, have transformed syrupy sentimental pieces into powerful flamenco whose interest and artistic worth may surpass the original non-flamenco versions. Consider the bolero Corazón Loco, first recorded in the honey-toasted voice of Antonio Machín. Miguel Vargas “Bambino” gives a searing interpretation that defies the limits of flamenco and its ability to raise gooseflesh. And for those of you thinking “but Bambino wasn’t exactly a flamenco singer”, be assured he knew and interpreted traditional cante at private gatherings of friends and family in Utrera, and that capacity fed his flamenco instincts to enable the transformation of popular music into hard-core flamenco, making him a cult figure.

Portada del cedé ‘Así fue’, de Bambino.

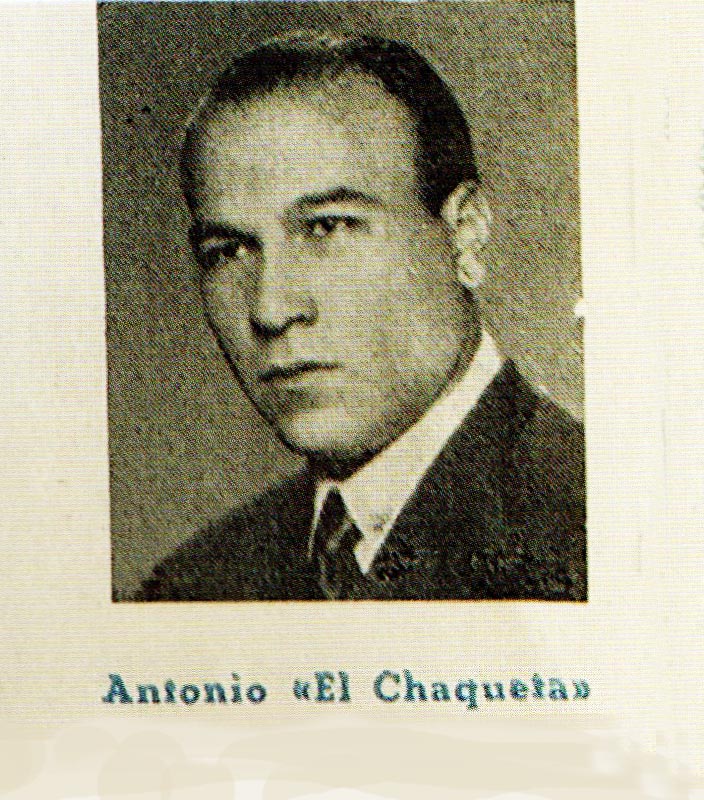

Another example is Adela la Chaqueta, and her unforgettable version of Voy a Perder la Cabeza por tu Amor. An inoffensive Caribbean-flavored love-song is pumped up to the verge of spontaneous combustion with an edgy delivery that leaves the listener exhausted. From the same family, the encyclopedic Antonio el Chaqueta was well-known for his talent for unique cuplé and impossible tongue-twisters.

El Romance de la Reina Mercedes, lush music and sentimental lyrics borrowed from the great tonadillera (songstress?), Concha Piquer. Bernarda de Utrera scooped up this romantic masterpiece, and ran with it. Other flamenco singers have included it in their repertoires, but no version is as gripping as Bernarda’s, one of many cuplés she infused with the scorching power of her personality. La Senda del Viento, in memory of Carmen Amaya, is another of her classics. Her sister Fernanda, though mostly known for her masterful soleá, also knew how to find flamenco through cuplé. Se nos Rompió el Amor plays in the minds of most flamenco fans in the voice of Fernanda de Utrera. Without leaving Utrera, there’s the great Gaspar de Utrera. Master of the most difficult forms, he had no problem squeezing flamenco out of a number of songs that became his trademark.

Where does all the energy come from? By knowing how to elongate or fragment the verses, modify the melody or the words, lengthen, repeat or adorn, the singer’s personality emerges, upstaging the music, and a cuplé por bulería is born. Keep in mind the very important issue of tempo. No matter how fast the guitar accompaniment is, the voice can serenely inhabit the compás at a pace the singer chooses because there is often no direct link between the sung notes and the guitar. The most flamenco cuplés present as bulerías rather than “songs accompanied por bulerías”. Creative interpreters move through the possibilities in search of the hotline to the jondo. And that’s where the magic happens.

Contraportada disco de Antonio El Chaqueta.