Carlos Ledermann: “Virtuosity is the order of the day”

Carlos Ledermann (Santiago de Chile 1955), for more than four decades maestro of flamenco guitar, concert musician, teacher and composer.

His capacity for work and his sensitivity, consistency, intelligence, artistic honesty and many other adjectives of this nature, are the qualities that make him the most noteworthy flamenco guitarist of his country, and probably of the entire South American continent. He has four full-length recordings, has studied with Manolo Sanlúcar and spent many intense hours with Paco de Lucía on numerous occasions. He has given countless recitals throughout the continent in addition to performing at the 30th Festival de la Guitarra de Córdoba and holds many prestigious prizes. Carlos Ledermann directs his own school of flamenco guitar and his foundation devoted to the musical arts of Chile. He is author of the book Identidad propia. Apuntes y sugerencias para la composición en la guitarra flamenca.

Carlos, in another interview you say: Flamenco is no long for Spaniards, it belongs to the world”. On the surface it sounds like you’re stating the obvious, that flamenco is known and admired internationally. But I sense a subtext, a certain disappointment or complaint that Spanish interpreters and flamenco followers may have, on occasion, turned their backs on you simply for being a foreigner.

All of us foreigners are exposed to that treatment for the mere fact of not being Spanish. Consider too that many Spaniards are underrated because they’re not Andalusian, but with time you accept it and it loses importance, you just keep moving ahead with your work. Nevertheless, flamenco is being interpreted throughout most of the Western world, and suddenly it’s being well-received, and no one is asking anyone’s “permission”, which is why I said and maintain that flamenco is no longer only for Spaniards. Just as Bach ceased to be only for Germans a very long time ago.

You began as a classical guitarist. What made you switch teams?

The wonderful possibility of creating and playing my own music. That, and the very different relationship flamencos have with the guitar, in this case with the music. I love classical guitar, but I had nothing to do there, it’s for a different kind of musician whom I admire unconditionally.

Are there flamenco singers and dancers in Chile? If so, do you play for them? Could it be said Chile has flamenco followers, albeit a limited number?

Don’t kid yourself, there’s a fair amount of flamenco fans, nowadays there’s a good audience for flamenco that didn’t exist 40 years ago. Of course it’s mostly dancers, just as in other countries. Singers, very few, which is also the case in other countries. I’ve accompanied at different times throughout my career, but it’s not what I generally do because first and foremost, I’m in love with the guitar, and the flamenco way of playing it, and the music it makes in that way, and that hasn’t changed.

How did you come to meet Paco de Lucía, and what relationship did you have with him?

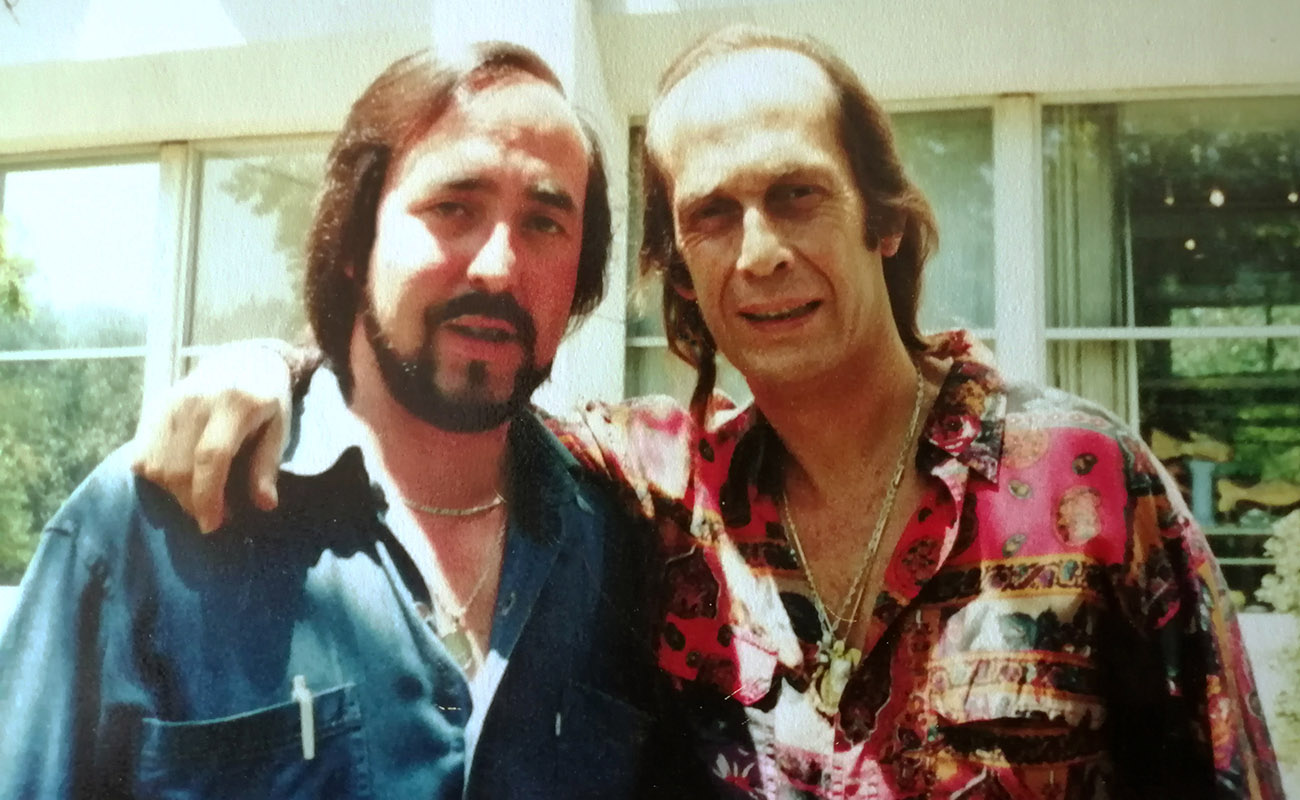

That year, 1980, Paco was brought by a group that organized important concert programing, and thanks to a tip from the director I found the hotel he was staying at. I had to wait a couple of hours because he was sleeping, but then he received me, not without first asking if I was a journalist. He was eating with the group that accompanied him on that tour, and then we stayed on alone conversing more than an hour. That’s what we did most of the time whenever he came to Chile: converse. I always remember one of those conversations a few years later that went on for about four hours during which time we emptied the room’s minibar while energetically debating several topics. I never knew why Paco offered me his friendship that lasted until the end. It was a valuable privilege, and for me, he never really left, he’s still here with all of us, more relevant than ever.

Manolo Sanlúcar has been important in your career. Are you still in contact with the maestro? How did he influence your way of understanding the guitar, and flamenco in general?

Manolo…of course he was important, I’d even say fundamental for me. I was with him in that unforgettable course of ’82 where I learned so much – I never finished learning from him – it was an entire world, a concept of flamenco and the guitar that was unknown to me, a certain kind of mysticism. I already considered flamenco to be a kind of music which is also danced; after that experience the concept was reinforced. With Manolo there were also countless hours of conversation, and it was all new to me. He is, or at least I feel this way, like a member of my family, an uncle perhaps, someone very close to me whom I love, the same with Ana. We haven’t been in contact for years, but that changes nothing.

Vicente Amigo was at that course…

Of course, Vicente was “Vicentito”, he was just 15 and already a master. Twenty-three years went by without seeing each other, and when we were reunited it was as if we’d just seen each other two days before, and time had only passed for us to get older. A terrific guy, straightforward, friendly, no airs of any kind, he doesn’t live on any Olympus. I think Vicente has unintentionally created a school. He still imitates Paco, but more so himself. His way of playing and understanding and feeling everything is very personal, and that set him on an alternative path. I hear Vicente in the music of many young guitarists who are the top of the profession today.

Observations on the teaching of flamenco.

Something I’ve been giving a lot of thought to recently, as well as written about, is the teaching of flamenco here in Latin America, both guitar and dance, because the classes are offered well enough, but then suddenly I notice important things are not taught, such as the characteristics of the styles, some history, the pioneers, the evolution, and I see very little interest in that sense. Guitarists are taught variations or complete compositions of this or that guitarist, but nothing is done to encourage personal creation. I don’t want to generalize, but that’s the situation most of the time. I’ve had students come to me from other teachers to whose classes they arrived knowing nothing, and the first thing they were taught was a riff of Diego del Morao – someone please explain to me, who can start out like that? I don’t know by what criteria, and according to what value system a young dancer is pushed up a notch at his or her dance school, because they usually know nothing about flamenco, only the steps they were taught, and there are very few schools that take an interest in anything else.

There are people who play well or dance well, but they don’t know how to teach because one thing doesn’t necessarily imply the other. I don’t see study programs, they must exist somewhere I’m sure, but in general I don’t see a well-thought out plan of study. For guitar, I think teachers should hold the instrument to the other side, as if they were left-handed, and maybe even reverse the order of the strings, so they can see what they themselves teach can be played in that way. Perhaps then they would understand what someone feels who is just starting out.

Do you follow the day-to-day goings-on of flamenco in Spain? What do you think about the direction being taken by flamenco guitar?

That’s a can of worms I’m not going to open so as not to go on too long, but naturally I try to keep up with everything that happens over there. As far as the direction taken by flamenco guitar, I think people are playing as never before, absolutely unbelievable, but it seems virtuosity takes precedence over content, it’s the order of the day, and the melodic line either disappears, or was never there in the first place, I see left hands that look like fast hungry spiders, but sometimes I don’t know what they’re hungry for, because I can’t find the music, or I don’t get the music there is. And for me, flamenco is music.

All images are from Carlos Ledermann’s personal collection.