Bulería por soleá or soleá por bulería… sorting it out

When it comes to flamenco song-forms, few terms are more ambiguous than bulería por soleá, soleá por bulería, bulería pa’ escuchar and bulerías al golpe.

When it comes to flamenco song-forms, few terms are more ambiguous than bulería por soleá, soleá por bulería, bulería pa’ escuchar and bulerías al golpe. Spoiler alert: they’re all the same family, not distant cousins but siblings, even though it may appear otherwise.

To say that confusion, disagreement, misconceptions and contradictory theories abound, would be a limp understatement, even as the issue continues to evolve. Definitions only go as far as people choose to apply them, words do not possess inherent meaning. If “rape” is a vile crime for English speakers, it’s a tasty medium-sized fish for Spaniards. How do you tell one usage from the other? The identity is in the context.

In flamenco singing, when the word “por” is used to name a song-form, it’s taken to mean that the first word, for example “fandango”, is being sung to the rhythm and form of the second one, for example “soleá”. Singer Manuel Vallejo worked artistic miracles with his “fandango por soleá” that cured fandangos of its occasionally histrionic delivery by adding the crisp discipline of compás, or steady rhythm. The creation has remained a part of the flamenco repertoire, especially cultivated in Utrera and Lebrija where singers seem to dislike free-form singing, preferring the structure of a steady beat.

Following the same system, if we refer to “soleá” por “bulería”, it’s logical to expect to hear standard soleá verses and melodies sung to standard bulerías rhythm and accompaniment. But such is not the case, thus, the confusion. Two variables, music and location, slice through the conventional practice described above leading to ambiguity.

The soleá por bulería, or bulería por soleá historically sung in the backrooms of Seville’s Alameda de Hércules in the first half of the last century, were not necessarily identical to what could be heard in Jerez, the city that has most actively cultivated these forms, although both repertoires were, and continue to be considered stylistic variations of the same “palo”, or group.

Now add the variable of the name. Well into the 20th century, recordings of these forms were labeled “soleares”, or sometimes, “bulerías”, despite clear differences in their respective characteristics, not to mention the loopy addition of interjections such as “mare de mi alma” or “compañera mía” among many others. These brief insertions seem to broadcast “Jerez!”, whose singers may or may not have created the custom, but enjoy the resulting rhythmic displacement. Add a wooden table or bar for knocking out the compás, eliminate the musical accompaniment, add some Jerez wine (“sherry” to you undocumented newbies), and the tableau is complete.

We still need to deal with “bulería pa’ escuchar”. This label is most often used by singers from the San Miguel neighborhood of Jerez, in particular the Agujetas family of singers. The quirky “soleá de Carapiera”, which is in the major mode of alegrías, is not a soleá at all, but a member of the soleá por bulería, bulería por soleá family of forms, commonly sung by interpreters from the Plazuela who call it “bulería pa’ escuchar”.

Consider too that in the interior, Lebrija, Utrera and Morón, soleá is usually interpreted with a rhythmic trot that is little different from standard bulería por soleá, as opposed to the laidback phrasing preferred by Jerez interpreters. Some years ago an attempt was made to apply the label soleá rítmica to soleá as interpreted in this interior zone, but that clumsy name hasn’t prospered.

“Bulerías al golpe”, as if the issue weren’t complicated enough, in the towns of Seville province is often, but not always, taken to mean the short-form bulerías compás of TAC-TAC-rest-TAC-TAC, as opposed to the standard 12-beat rhythm. Elderly guitarists also remember the term “al golpe” being used to describe the terse choppy guitar-playing typical of Manolo de Huelva and Niño Ricardo. In Jerez however, “bulerías al golpe” is yet another label for this group of song-forms we’re trying to pin down.

The bottom line is, yes, a different spin may be given in different locations, as happens with any other flamenco form, and diverse labels may or may not be applied, but it’s all one big family, open to improvisation as bulerías is (the expansive Capullo de Jerez makes good use of this liberty), not to be confused with soleá, nor thrown into the same sack.

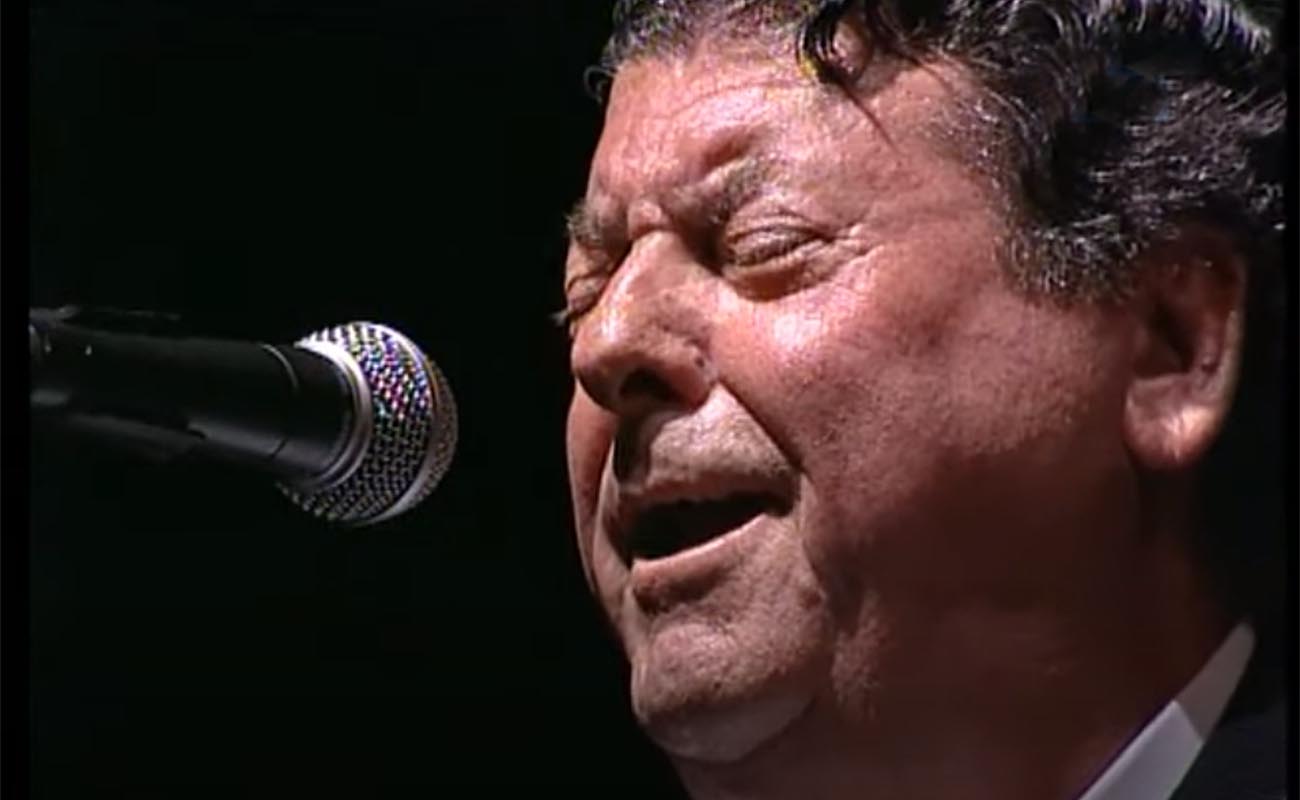

To savor the peculiar feel of these forms, listen to Tío Borrico, Niño Gloria, Manuel Agujetas, Niña de los Peines, Tomás Pavón, Antonio Nuñez “Chocolate”, Luis Zambo and the great Manuel Soto “Sordera” who did so much to define and enrich them.

Top image: Manuel Agujetas. Photo: Estela Zatania

Quijote 15 June, 2021

I have always thought of the compás of Soleá por Buleria to be more like Alegrias with soleá chords. Like everything in the art, there are variations…..

Esmeralda Enrique 20 June, 2021

Thank you, Estela, for writing on this subject. I have been so baffled as to how to explain these differences to my students. Un saludo!