Anzonini: special report on the bohemian from Puerto de Santa María

Not exactly a flamenco singer, nor precisely a dancer, but both, and much more. A festero. That flamenco specialty so difficult to define, so fundamental.

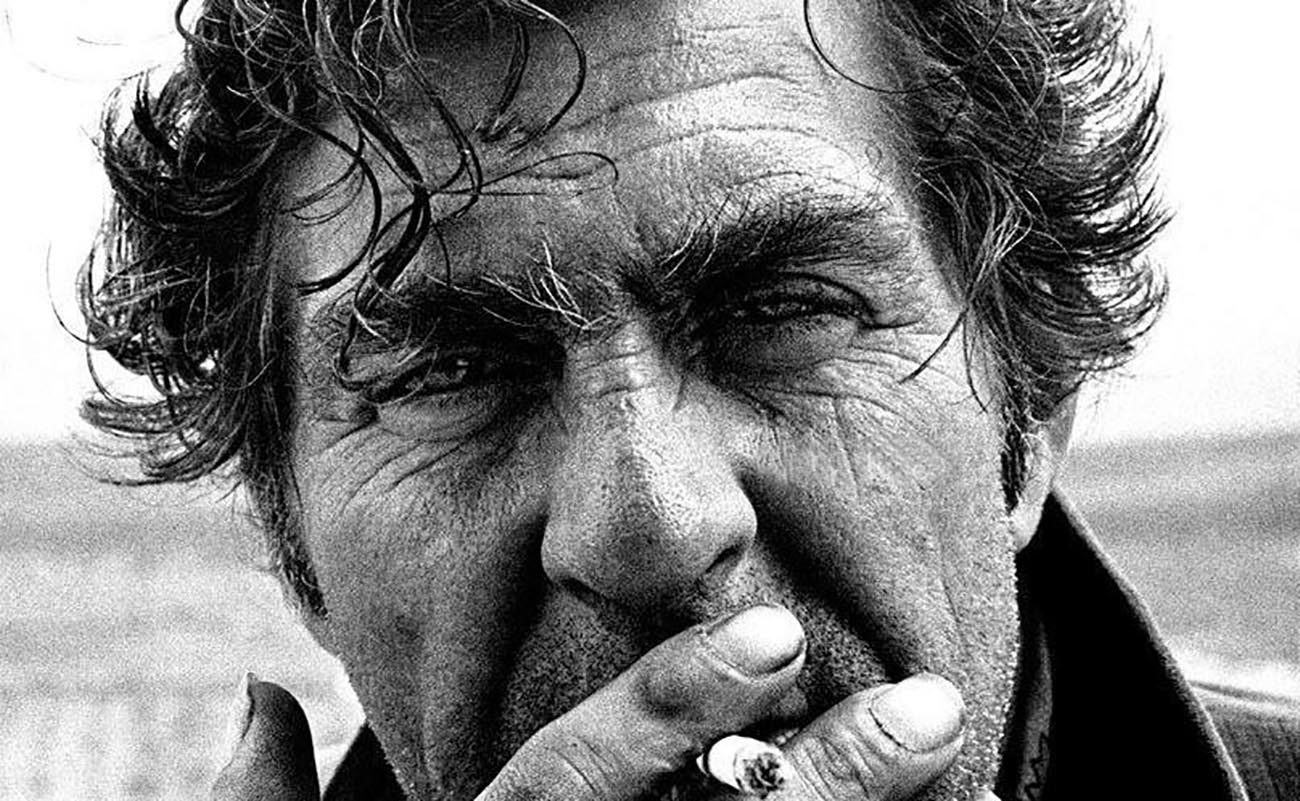

Photo: Tony Keeler

Manuel Bermúdez Junquera, “Anzonini del Puerto”. Legendary dancer/singer of fiesta flamenco for those of a certain age, and nearly unknown in the current fast-paced world of promotion via social media, international festivals and public sponsorship. Born in 1917, he left the planet in 1983 and in those 66 years between one date and the other, he enriched the atmosphere with his original take on flamenco. Not exactly a flamenco singer, nor precisely a dancer, but both, and much more. A festero. That flamenco specialty so difficult to define, so fundamental.

Now, more than three decades after his passing, a grandson of Anzonini’s has lovingly taken on the job of reviving and honoring the inimitable art of his grandfather with a series of talks. Antonio Macías Bermúdez discusses the project.

Antonio, when did you first realize your grandfather had been a well-known flamenco personality?

Ever since I can remember. In Puerto de Santa María he was known by everyone, people always talked about him, his appearance, blond with blue eyes, his stature, his restrained elegant way of dancing and his extraordinary compás, out of the ordinary, and that he played castanets with all his fingers. My grandmother always used to say he was “an artist’s artist”. Ever since childhood I heard stories and anecdotes about the people who visited my grandfather’s house: La Perla de Cádiz, El Beni, Miguel Funi, Paco Valdepeñas, Los Paulera of Jerez, Los Sordera, Terremoto, Lola Flores, a very young Rancapino and his brother Orillo, Pansequito, El Negro del Puerto and many others seeking out Anzonini. When I was old enough to understand the dimension of all these people, I began to realize my grandfather’s importance within flamenco.

Is he remembered in Puerto de Santa María? Were you in contact with him?

As time passes there are fewer and fewer people who had direct contact with him, his contemporaries are over 60, but whenever I come across someone who knew him, they tend to remember Anzonini with emotion and nostalgia. Young flamenco fans know who he was, but not those foreign to flamenco. What’s really surprising is coming across foreigners, mostly Americans, who knew him or know of his fame.

The reason I’m doing this series Anzonini del Puerto, Cien años de Compás is precisely in order to preserve the memory of who he was, sometimes I think there ought to be some public recognition, but of course, the administration is precisely the sector that knows the least about Anzonini.

My grandfather died in 1983 when I was just 14, I remember him with affection, he used to visit us now and again around the beginning of the 1970s when he was living between Morón de la Frontera and Málaga. Towards the end of the decade he moved to California although he occasionally returned to visit us.

You’ve put together a fine presentation about Anzonini, where is it being presented? How are people reacting?

In 2016 the Ermitaño Cultural Association in Puerto de Santa María proposed doing a talk about flamenco to help people distinguish the various flamenco forms. This conference was called The ABCs of Flamenco Formsand it was very well-received. In 2018 I was asked to do another series of talks, always based on flamenco. I proposed the topic Anzonini del Puerto, A Hundred Years of Rhythm, a reference to the centennial of my grandfather’s birth. I debuted the talk in the summer of 2018 at the Tomás el Nitri flamenco association in El Puerto for friends, relatives and locals with the attendance of people who had known Anzonini in Spain or in the United States.

Thanks to Jerónimo Velasco in Morón de la Frontera, the organization of the Gazpacho flamenco festival of 2018 included the talk within the parallel cultural activities of this event, including the performance of two terrific singers, Antonio “El Carpintero” and Antonio Chacón, both of whom had been flamenco buddies of Anzonini’s.

The next talk is at the Hospitalito Municipal Museum in El Puerto, an activity organized within the 21stedition of the Fiesta de los Patios of Puerto de Santa María devoted to Flamenco Dance.

What was Anzonini’s relationship with Morón de la Frontera?

Morón adopted Anzonini and was absorbed by the Morón flamenco scene around 1963. He was looking for a canvass to paint his bohemian soul, and found it in Morón. His friendship with Diego del Gastor, Fernandillo de Morón, Joselero, Andorrano, Agustín Ríos, Juan andPaco del Gastoramong others, in addition to the proximity of Utrera with Fernanda, Bernarda andPerrate, and Alcalá de Guadaíra with Manolito de María, was the perfect setting to cultivate a kind of flamenco that was free, inspired, spontaneous and fresh.

In the flamenco ambience of that era, well-to-do patrons played an important part. They were the ones who organized gatherings in which these artists would perform. Particularly noteworthy was the firm relationship between Anzonini and the businessmen Antonio and Ángel Camacho of Morón.

Add to this the revolution that took place due to the large number of Americans who went to study flamenco, attracted by the guitar-playing of Diego del Gastor, many of them lodged at the Finca Espartero run by Donn Pohren where organized fiestas gave additional support, both economic and artistic to the artists of the era.

How did you go about gathering data for this investigation?

At home, from the time I was small, we were always awaiting news about grandfather Anzonini, there was always someone who had run into him at the bullfight or at some fiesta. We were continually collecting documents, photographs and posters that came our way. In 2001 I met Andrés González Gómez on an internet forum devoted to flamenco. After carrying out an exhaustive investigation, he published his book Al compás de Anzonini del Puertoin 2013. I was fortunate enough to collaborate with the author on the part regarding the era of Anzonini in Puerto de Santa María, searching for and providing information, organizing meetings with friends and relatives of Anzonini, all of which allowed me to delve into the people surrounding him. The investigation carried out by this author, both in Spain and the U.S. has made it possible to access a great deal of information about which I’d had no former knowledge.

At the same time, I met Jerónimo Velasco of Morón de la Frontera at the book presentation, and we became great friends. Jerónimo is involved in the organization of the Gazpacho festival of Morón since the its beginning. A great deal of information comes from Jerónimo’s Fondo Flamenco, and much data furnished by flamencos of the era has made it possible to get a glimpse of what those times were like.

You play the guitar, and you also dabble in singing and dance. Do you aspire to follow in your grandfather’s footsteps?

Flamenco has fascinated me ever since childhood, I began playing the guitar when I was eight, and when I got older I studied in Jerez with “El Carbonero”. I sing and dance however it comes out, in this respect I have very little discipline. It seems like a great responsibility, and I rarely get up on stage. I think my grandfather felt the same way, I prefer close-up informal flamenco, the improvised get-together and having a good time at an informal party. In this sense I aspire to be like Anzonini, to enjoy the kind of flamenco that just happens and isn’t premeditated. Anzonini didn’t approach flamenco as a job, he developed a philosophy of life using the vehicle of flamenco.

Does your family like flamenco? Are there any other artists?

Flamenco is rooted in my family, I was born listening to flamenco. Anzonini’s descendants are few: my mother had three children and my aunt, four. One way or another, each one has been touched by flamenco, but none has become a professional artist.

Did Anzonini create a school, or did he follow an established path?

It’s clear that Anzonini left his personal mark in dance and that he did something special and genuine, in the same line but different from all the other fiesta artists. One way or another he contributed a style that led the way for current artists.

Although I’m not able to corroborate this, a cousin of his, María Bermúdez from Jerez de la Frontera, (no relation to the current dancer of the same name), speaking about her infancy when the cousins lived together at the age of 13 or 14, told me that Anzonini was always marking flamenco rhythms, playing castanets, adopting gestures and bits of dance.

There are also references that Anzonini followed a style expressed by “Las Coquineras”, especially the fiesta dancer Antonia Gallardo “La Coquinera” (1874-1942).

What do you know about Anzonini’s years in the United States?

That’s a very big question. I’ve had contact with some of the Americans who spent time with him, for example Paul Shalmy who accompanied my grandfather and was at my house during his last visit in the spring of 1983. I know it was he who helped Anzonini move to California in the middle of the seventies. My grandfather was very well-received and carved out a place for himself at Berkeley. He gave flamenco dance classes and made the most of his aptitudes as cook and butcher, selling sausages he made with artisan methods, thus allowing him to subsist. There are many anecdotes about this.

During his stay in the U.S., he participated in a documentary about the importance of garlic in a variety of cultures, and of course, he represented the Spanish part. The documentary was produced by Less Blanc, Garlic is as Good as Ten Mothers, an absolute jewel!

I know he also was connected with the universities of San Diego in California and Washington, giving talks in which he was accompanied by dancer Marcia Sánchez “La Romera”, guitarists Kenny Parker, Gerardo Hayes, David Serva and Chris Carnes among others. He had a special connection with the ethnomusicology department of the University of Washington with whom he collaborated on many occasions. I also have indications that he made contact with Sabicas.

What is the legacy of Anzonini’s flamenco? Is he still relevant for the current generation?

The new generation of fiesta interpreters, no matter how young they are, have the reference of Anzonini and his special way with the dance, particularly in the triangle of Seville, Cádiz and Málaga. But what’s really surprising is the community of flamenco fans he created in California, giving continuity to the seed that came about in the 1960s.

Do you think the art of the flamenco festero is in danger of extinction?

I believe there are tendencies that are more developed in one era than others, it’s obvious flamenco evolves just as society evolves, since it follows a way of externalizing emotion. Nowadays we have a crossing of industry with an economic component that is difficult to sort out, and it’s possible not all flamenco can find a place in this powerful swirl of production. This isn’t the sword of Damocles of fiesta artists, but clearly it endangers development. The figure of the festero will surely continue to thrive in its own habitat of up-close flamenco and inspiration and will be reserved for those fortunate enough to witness it, as has always been the case.

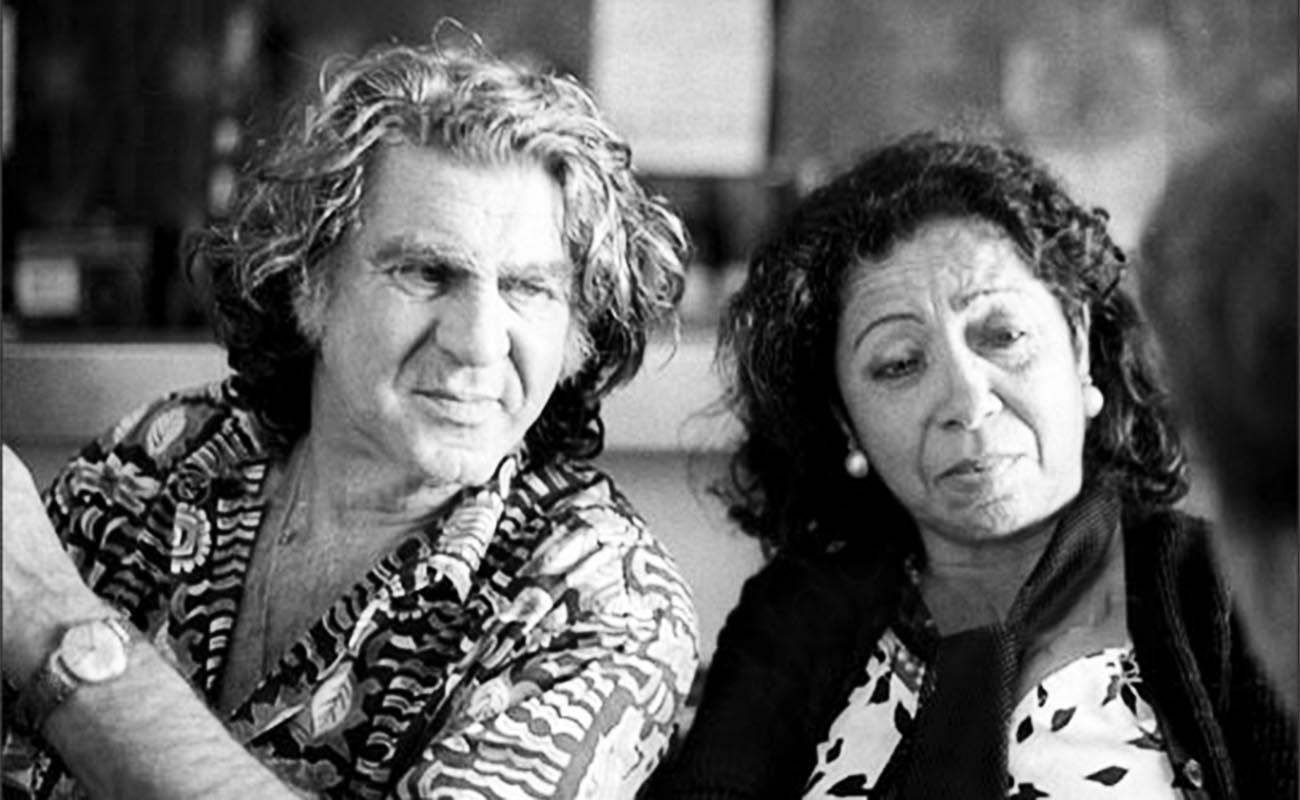

Anzonini con Fernanda de Utrera. Foto: Robert Klein