Antonio Santaella: Granada’s unknown maestro

While the rest of us are struggling to manage the complicated present situation, a maestro of flamenco dance, 85 well-kept years of age, with the aesthetic of Federico García Lorca engraved in each molecule of his being, follows his path with conviction and dignity.

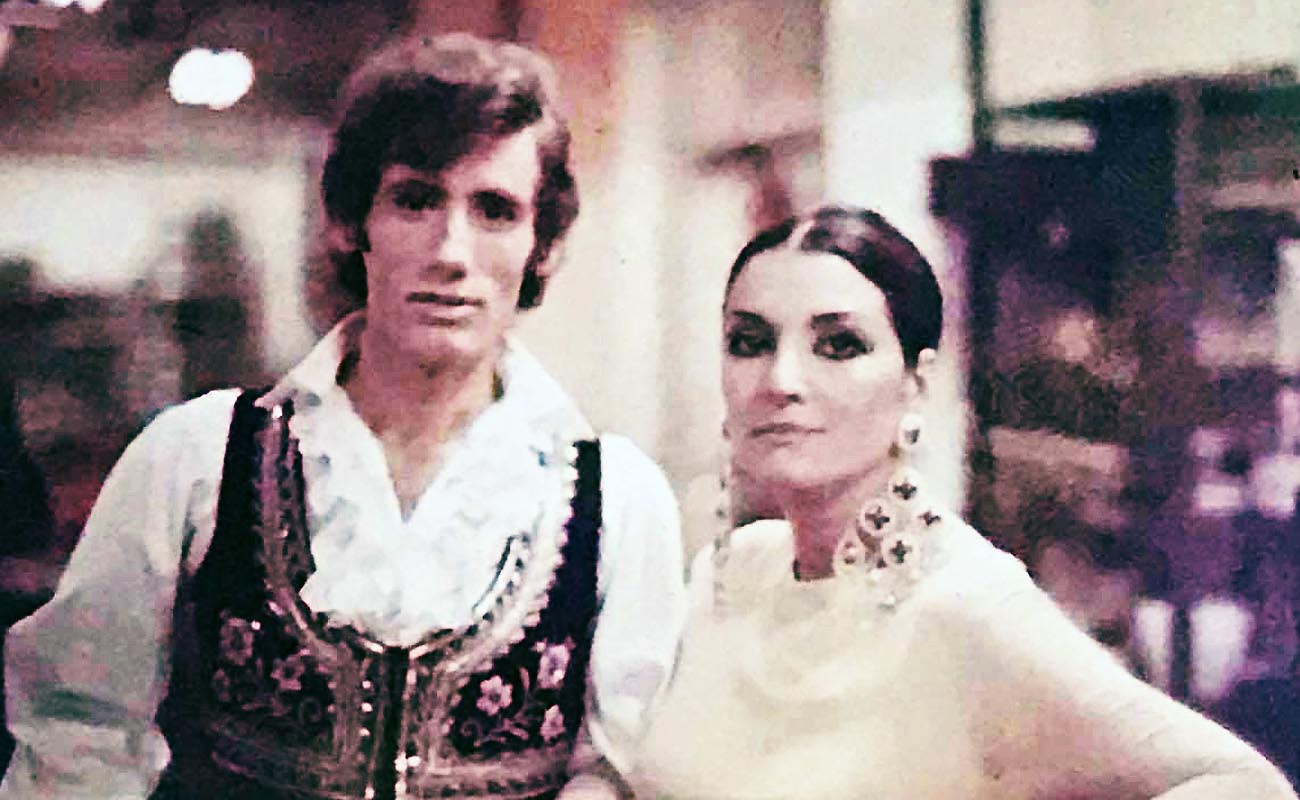

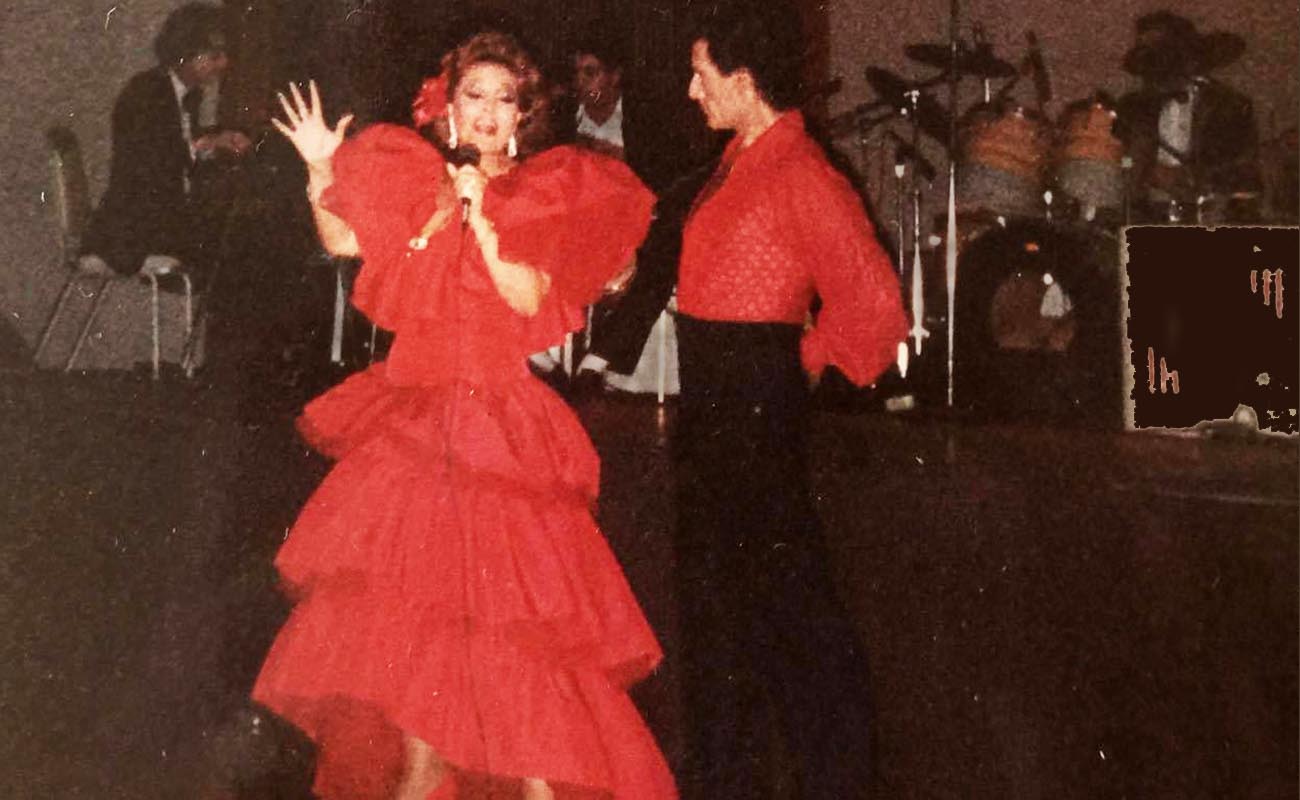

As I peruse the images and clippings of his long professional life, I know people of narrow vision, seeing the typical brimmed hat and polkadot scarves, would disdainfully cross him off as a “tablao dancer”. But Antonio Santaella goes way beyond that. True enough, he was fully active in that fruitful era, but his elegant personality has always kept him a class act. He has presented his personal vision of flamenco and Spanish dance in numerous theaters and other formal settings, with his admiration for Lorca always shining through. In addition to flamenco, he commands knowledge of regional Spanish and semi classical dances, and is credited as choreographer, director and creator for a long list of danced narrative works.

Discipline, formality, dedication and a profound love of his culture are the characteristics that best define the artistic and human qualities of Antonio Santaella.

Antonio, what were your beginnings?

I was born in a town on the Granada plain called Valderrubio, where García Lorca’s father had the most fertile land of the whole area. Lorca would spend his summers there, which became a source of inspiration for much of his work. I lived with my mother and siblings, and my love of flamenco didn’t come from the family, I picked it up from gypsy families in the neighborhood.

When I was 14, my father, who was in France from the end of the civil war, like so many other Spaniards fleeing from those horrible times, took me, the youngest child, and my mother, to live with him in France. That’s where I learned my first flamenco moves. Since I loved flamenco singing and dance ever since I was small, it was easier for me to get the aesthetic than for others not born in Spain.

The early years were horrible, sheer desperation. That changed when I made friends in a gypsy family who were friends of my father’s, and who had arrived in France under similar circumstances. One of the boys played a little guitar, and that was all I needed to feel close to my roots. We invented dance steps and I tried to imitate Pepe Pinto, it was so joyful! One day we took a train to Paris, and passing through Pigalle, we heard the sound of castanets. They told us is was the maestro Rayito giving dance and guitar classes…at that moment the heavens seemed to open! And that’s how my career as a flamenco dancer got under way.

There was a lot of work in Paris at the time. At La Guitare I crossed paths with Los Gitanillos de Cádiz, Bendito, Ana María and Cascarilla, at the Teatre de l’Etoile, with the Príncipe Gitano and at the Olympia with Rafael Aguilar.

Your work is strongly inspired in Lorca. What does Federico represent for you?

Lorca is my inspiration and motivation to create. You can’t hear flamenco without thinking of him. You can feel his presence in everything I do! Remember I was born in the town where he spent a large part of his creative life.

From France, to New York, to Puerto Rico

I worked at a tablao in Paris where the dancer Laura Toledo saw me and signed me up to tour the United States for two and a half years. I ended up in New York where I made my own group and worked at the elegant Chateau Madrid, in addition to a wonderful opportunity to do Carnegie Hall. It was a fabulous experience, and many doors opened after that.

I went to Puerto Rico with a contract for the Hotel El Convento where we stayed a long time. In the beginning people asked me for classes, and I kept putting it off, until I finally decided to teach, and here I am, a half-century later. Puerto Ricans really feel flamenco, and they express it very well! Many of my students have become professional, some are in Spain, and in other European countries, the United States and Canada, I’m very proud of them.

At one point, when the University of Puerto Rico was holding a Symposium of Poetry and Literature of the Americas, the Caribbean and Spain, they commissioned me to do a choreography for the closing day. It went so well I said to myself this is for me! After that, although I continued to perform in hotels, my dream was to create works with cultural significance. And there were many, including a work for youngsters from ten to seventeen in which I explore all the problems that come with leaving school at a vulnerable age.

Do you stay in contact with Spain?

In the nineteen-seventies, I took time out to go to Spain and enjoy my country, and I took classes with Antonio Marín as I had in earlier years. Since it was a long stay, I made a group and we were hired by Pasapoga on Madrid’s Gran Vía. I took Carmen Linares to sing, she was 16 years old and just debuting as a flamenco singer. The show was called Antonio Santaella y su Suite Flamenca. From there, I returned to New York to the Chateau Madrid. We were Nati Mistral y Antonio Santaella y sus Flamencos. Aside from that, I spend time in Granada every year.

You’ve had large dance companies, and inserted flamenco culture in Puerto Rico thanks to your knowledge, and high-quality shows. Is your contribution valued in Puerto Rico? Have you received financial support?

I’ve been helped by the Culture Institute and Endowment for the Performing Arts. Yes, I feel my work is appreciated here! I received recognition from the Senate, diplomas from all over the island, the Gold Medal of Julia de Burgos, the medal of the Puerto Rican branch of the UNESCO, first prize from the Worldwide Dance Competition and many honorific plaques.

Do you follow the evolution of flamenco dance in Spain? What do you think about the work of avant-garde dancers such as Israel Galván?

Yes, of course, evolution is inevitable, the world doesn’t stop! In flamenco, and especially choreography, you have to be creative. Without evolution you wouldn’t be able to express and explore the surrealism of a given topic. As far as Israel, I’ve tried to understand him, and at times I manage to do so. When it comes to flamenco singing, that’s something else, I like the traditional approach, and feeling my insides churn when I hear a siguiriya of Tomás Pavón, Niña de los Peines, Mairena. That isn’t as likely to happen with evolutionary singers. Although I also accept and admire the evolution of the cante, because it’s a vital living expression, and it has to move with the times, but it mustn’t become detached from the essence, because then it would turn into something else.

In what way have you been affected by the pandemic?

Like every other country, in Puerto Rico we’re suffering with the terrible virus that extends more and more every day, possibly due to the flow of visitors from the United States, and the non-observance of protocol imposed by the government.

The legendary tablao Gitanerías, that I inaugurated so many years ago, closed in March, and reopened the end of April, adhering to the law of 30 percent capacity. In the meantime, like everyone else, our hopes are pinned on the vaccine.

All images are from Antonio Santaella’s private collection.