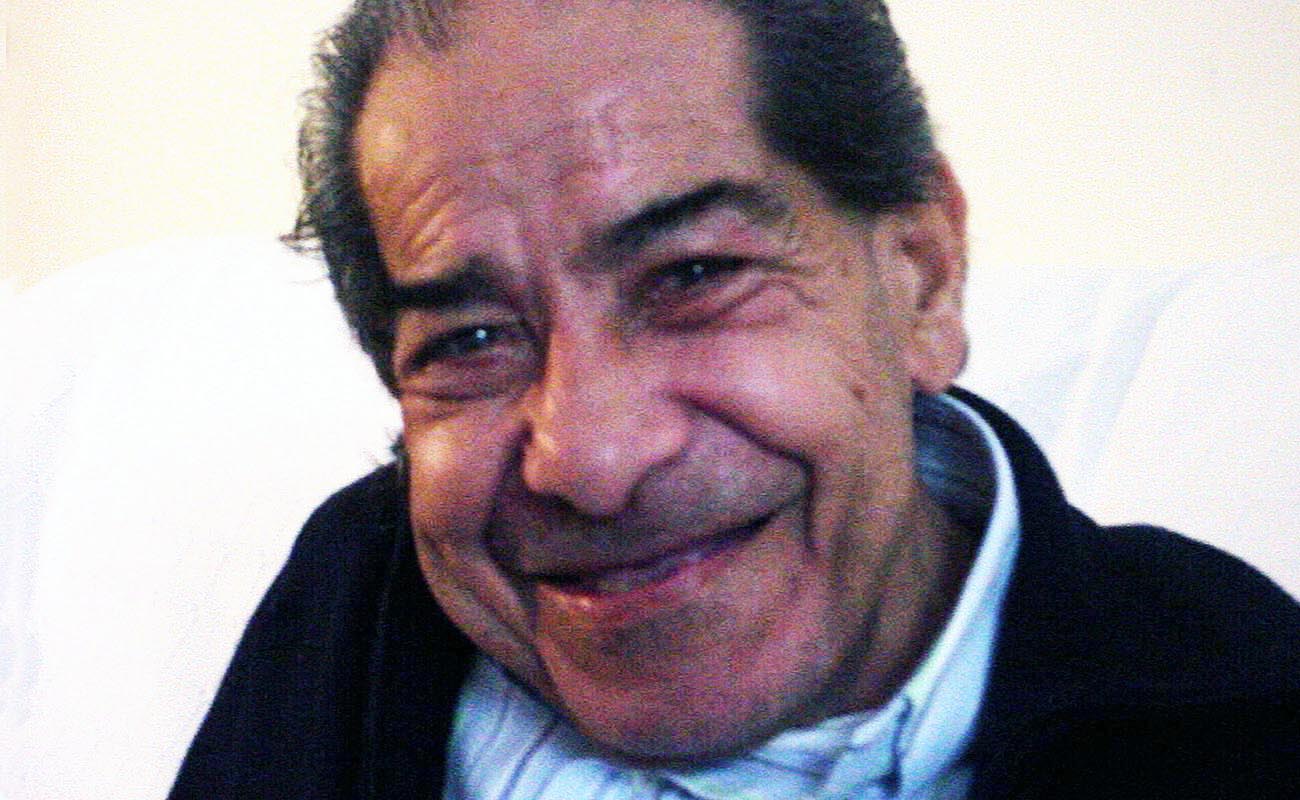

Antonio Mairena, portrait of a singer and his times

Antonio Mairena, dignity, respect, rejection of all fictitious exaggeration, and unconditional veneration for elders as an absolute guiding principle. Majestic singing that reaches a profound essence without stridency or histrionics.

Once upon a time, there was Jerez flamenco singing, a heritage and tradition, with talented interpreters and a way of singing that practically defines classic flamenco. Then came Antonio Mairena giving body and coherence to the songs, magnifying them without diminishing their essence. “He who knows the most about flamenco knows only ten percent,” famous words from the maestro.

Antonio Mairena made use of flamenco, not seeking to possess it but to make use of its forms, treading carefully and leaving them intact, without compromising their integrity, aiming to create within the existing framework. He rescued forms and songs that even the people of Jerez had practically abandoned. Researchers Luis and Ramón Soler state in Los Cantes de Antonio Mairena (2004) that “many singers from the area [of Jerez] have forgotten the songs of Marrurro, Loco Mateo, Manuel Molina, and Paco la Luz.” Mairena preserved them with utmost care and wisdom, offering them on a platter for future generations.

The day Antonio died in 1983, I was in Catalonia. An Andalusian waiter with a look of disbelief broke the news to me, and in silence, we exchanged a glance sharing the same thought: “What do we do now?” We still had the undisputed maestro Antonio Fernández Díaz Fosforito, but that was a different kind of mastery. Fosforito didn’t boast. He didn’t write books or develop grandiose theories, and certainly didn’t defend fanciful stories about the razón incorpórea (autochthonous legitimacy?) or a hermetic era, concepts which today are discreetly set aside by Mairena’s followers.

The flamenco championed by Antonio Mairena is what many nowadays want to call “pure.” If not taken literally, the label serves its purpose because we all understand what it refers to. Some use the term neojondo with subtle offensive intent to refer to an outdated concern for preserving the forms.

In 1959, Mairena was appointed Honorary Lifetime Director of the Cátedra de Flamencología, and shortly afterwards, he participated in the festival organized by the same institution in honor of Manuel Torre. This event marked the placement of a commemorative plaque at the house where the famous singer, greatly admired by Antonio Mairena was born. In 1964, he was awarded the National Research Prize for his book Mundo y Formas del Cante Flamenco, written in collaboration with the poet and flamenco expert from Córdoba, Ricardo Molina.

In the nineteen-seventies, Antonio Mairena had no choice but to accept Lole and Manuel, La Susi, Remedios, and the entire phenomenon of Andalusian rock under the umbrella of flamenco because public opinion was strongly pulling in that direction. It wasn’t the start of a new wave, no. It was a tsunami of exotic harmonies, slowed-down rhythms, nonayno choruses, the cajón and a contemporary canastero sound cultivated by the great pairing of Paco and Camarón, that duo which the god of flamenco placed in our path to lead us by the hand towards a new horizon.

The reign of the fandango lasted for decades, but Mairena’s influence in major festivals led to these songs he considered inferior being seldom heard. The end of shows shifted to bulerías with a closing round of tonás, a tradition still alive at the Reunión de Cante Jondo in La Puebla de Cazalla.

In the history of flamenco singing, there have always been antagonistic pairs: Torre and Chacón… Marchena and Valderrama… Camarón and Pansequito… In this context, the pair that most clearly divides fans is that of Antonio Mairena and Manolo Caracol, both born in 1909. It’s not usual the same person considers both singers indispensable.

Antonio Mairena, dignity, respect, rejection of all fictitious exaggeration, and unconditional veneration for elders as an absolute guiding principle. Majestic singing that reaches a profound essence without stridency or histrionics. Caracol, possessor of an enviable echo, communicative power, and a natural ability to deliver his singing with depth, inspiration, and a deeply personal touch. The history of 20th-century flamenco singing cannot be understood without either of these singers.