A chat with Enrique el Extremeño

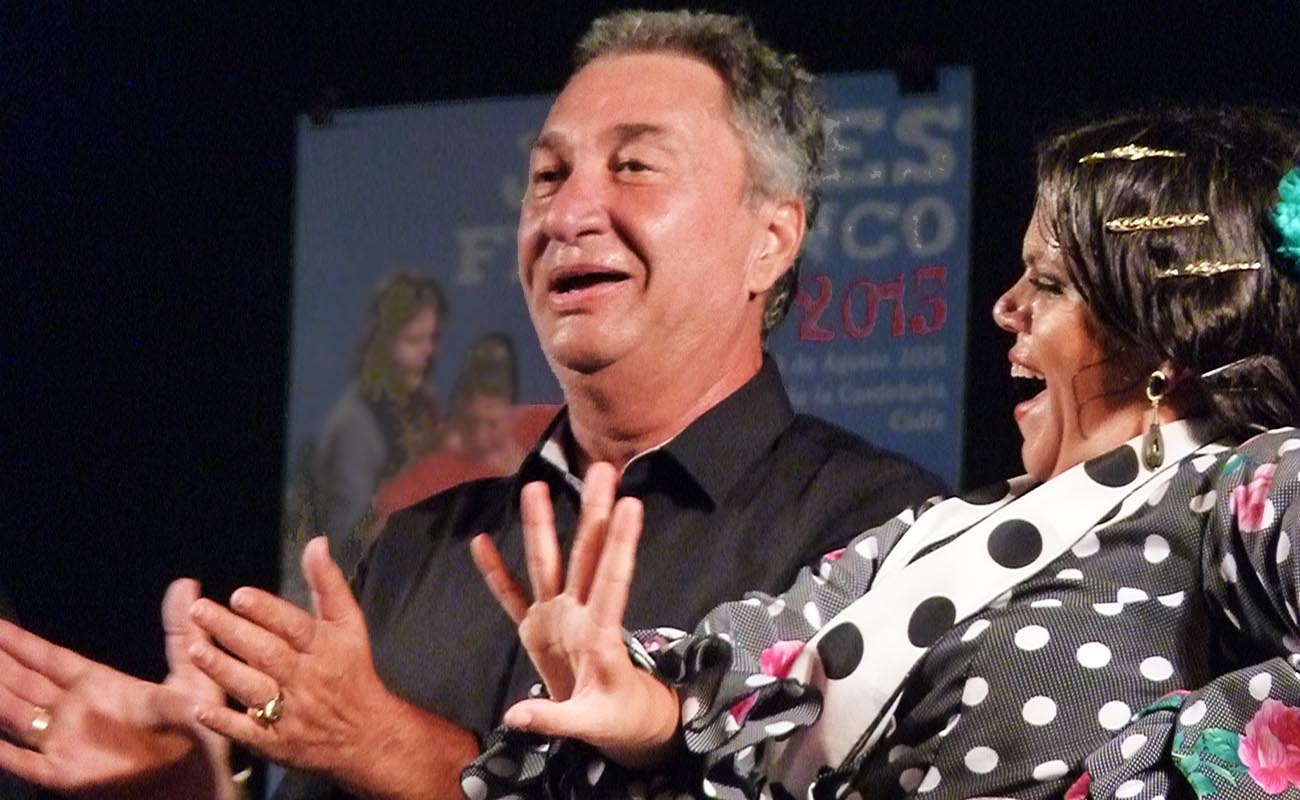

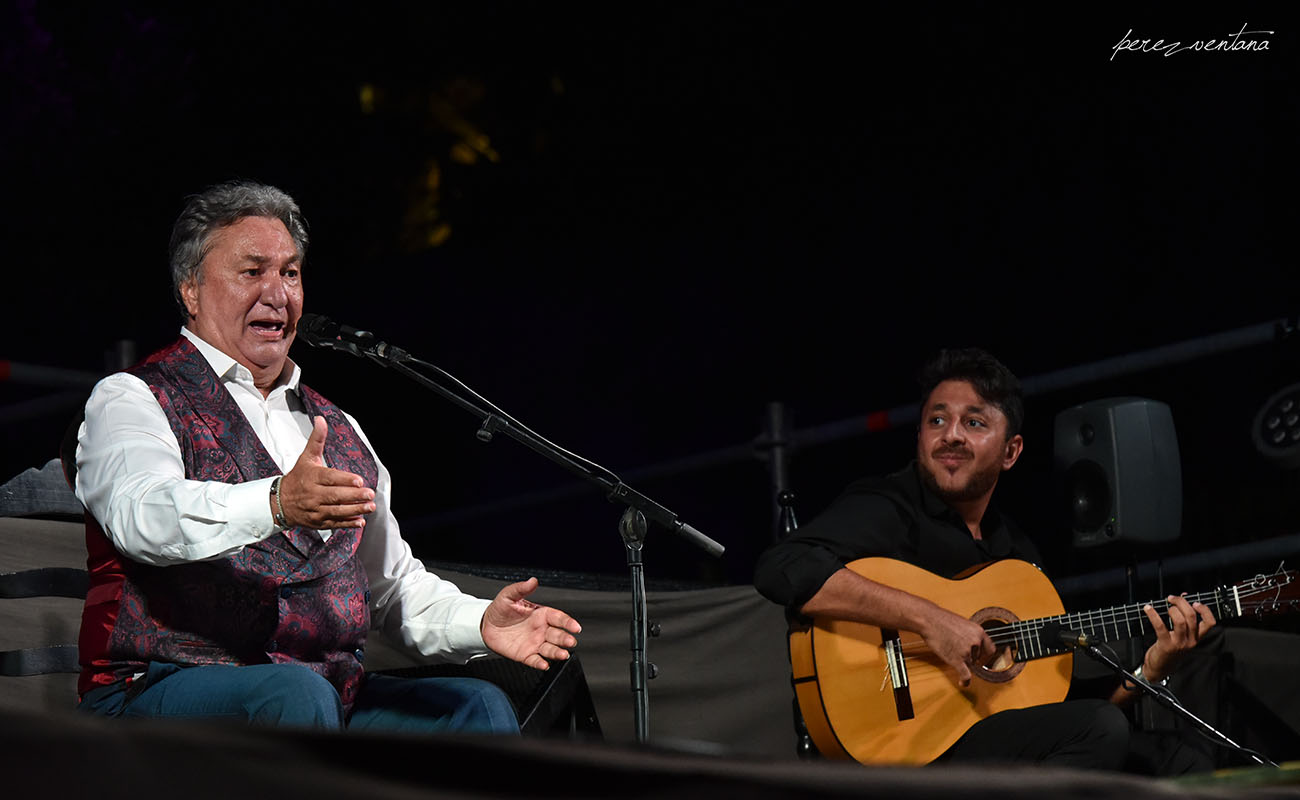

Enrique El Extremeño is one of the most sought-after singers for flamenco dance.

Juan Antonio Santiago Salazar (Zafra 1954), flamenco singer, father and spouse of artists. Known to flamenco fans as Enrique el Extremeño. His powerful delivery passes through the sieve of sensitivity some interpreters manage to find in flamenco. I saw him the first time decades ago singing for the great dancer Manuela Carrasco when the flamenco of polkadots and ruffled shirts didn’t trigger embarrassment in followers of the genre. That soleá, the sublime communication between Enrique’s voice and the goddess of flamenco dance who was recently named Hija Predilecta (favorite daughter) of Seville, that soleá was just about all you needed to know about this basic flamenco form.

After that initial discovery, I would see el Extremeño again and again, at the Bienal de Sevilla, Festival de Nimes, Festival de Jerez, Mont-de-Marsan, Alburquerque, Festival de Granada, etc., with all the greatest dancers, becoming, with his expressive voice, one of the most sought-after singers for flamenco dance.

Extremadura, Huelva and Utrera, you come from three major singing zones, yet you have an absolutely original and unmistakable personality. What are your artistic references, your sources?

When I was starting out, I was mostly listening to Antonio Mairena, but afterwards my real maestro has been José Salazar, that’s where I mostly learned, but you never stop learning, you get things from everyone, and having worked at all the Madrid tablaos, you learn a little from one, and a little from another, but I’m mostly indebted to Mairena and José Salazar.

In order to specialize in singing for dance, you have to know all the rhythmic forms. How do you learn to sing for dance?

Singing for dance has its mystery, but can be learned. Basically, you begin at a tablao, that’s where your initial learning takes place, and when you pass that phase, that’s when you begin to sing for major dancers, and you become familiar with what they do. Singing for dance is different from singing alone. There are people who’ve never sung for dance, or haven’t worked at a tablao, and they’ll never sing for dancers the way people with tablao experience do, it’s a different approach, when you’re singing for a dancer you have to rein in your delivery somewhat. A solo singer can do anything he or she likes. In order to sing for dance, you just have to keep your eye on the dancer, get to know their work, and you have to like flamenco dance.

You and Manuela Carrasco made history. That was the beginning of your well-deserved fame as a singer for dance. In earlier times cantaores were not always identified on dance programs. Now flamenco followers know who’s who and have their favorites.

Critics have changed a lot. It used to be everything was centered on the dancer, and with a few exceptions, singers for dance didn’t stand out. But when interpreters like Juan José or myself or José de Lebrija came out singing a little different, the critics sat up and took note, and nowadays we regularly get mentioned, and flamenco fans know us as well, you go somewhere to perform and they say things like great job singing!, they notice what you do.

Who’s the boss on stage, the singer, the dancer or the guitarist?

On-stage it’s the dancer who’s in charge. But the guitarist has a big responsibility because he has to be on top of everything the dancer does, and then the singer as well, there are moments when a single gesture from the dancer requires a response from the guitarist, while at the same time the singer must be supported. And the singer must know what the dancer wants at any given moment, accompanying as best as possible to avoid problems of tempo or compás. It’s a collaboration of all three elements, but the dancer always has the last word.

Is it more “important” to sing solo than to accompany dance? Which do you prefer?

What every interpreter wants is to become a star, but there are also stars singing for dance. I’ve always enjoyed singing for dancers, but I also like doing recitals and people being able to listen to me on my own, and precisely now I’ve been doing many things. Without a doubt there are some who prefer singing for dance, but you can be sure they would love to go solo, that’s the culmination for an artist.

A couple of decades ago it was enough for a singer to be on top of the song-forms, but now you often need to learn a script or story-line, play a part or even learn verses or songs written specifically for a work. In your unforgettable role in the Cervantes piece Rinconete y Cortadillo, we were all surprised by your acting talent. That was more than 20 years ago, nowadays it’s normal to see flamenco musicians interpret a role. How do you feel about this?

I had a ball doing Rinconete y Cortadillo because I love acting, I’d done other things as well, I’d dressed up as a miner, I worked with Milagros Pérez, I was in Andalucía en Pie, a part for which I had to dress up as an Arab, and then as a gypsy… I’ve done a lot of things, all artists enjoy doing this. And nowadays, dancers like their people to know how to act.

You spent extended periods working in Japan. How was that experience? Do you think flamenco singing can communicate emotion even when the listeners don’t know the language?

In Japan it was the tablao of a friend of mine who brought “millions” of artists, you can’t name one who hasn’t passed through his place. He initially asked for 4 dancers, two or three singers, guitarists, I took care of the paperwork and we were there 12 years, the Sala Andaluza it’s called. Everyone was happy working there, and let me tell you, the best “oles” I ever heard were from native Japanese in that club, because they’ve learned in such a way that they even know how to cheer just right and at the right moments. And right now there’s a line-up of dancers who I dare say some of them could do very well working in Spain.

I remember seeing you at the Alburquerque festival a few years ago. Marisol Encinias the director decided to put on a flamenco singing recital for the first time, with no dancing, featuring you and Juan José Amador. What was it like singing for people who had always seen flamenco as a dance and guitar form?

Well, the Festival de Alburquerque was very nice because I also gave a flamenco singing course for 60 people, there was no room for more. Afterwards, the theater was full for the recital Juan José and I gave. It was an important event, because we’d given cante recitals in Spain, but never abroad, and you never know how people are going to react. We were given that opportunity and the audience was very grateful, it was very rewarding.

Pingback:La Voz Flamenca TEMPLATE – Flamenco Vivo Carlota Santana 28 October, 2022