What I liked about Antonio Mairena

He was the leader of cante for twenty years, leaving an outstanding discography and creating one of the best schools of cante of the 20th century. Besides, he did this at a crucial moment, when the last gasps of the ópera flamenca were seriously harming flamenco. I admire the merit of this Gypsy from Mairena del Alcor, who had so

A few days ago, a die-hard mairenista asked me in jest if there was anything at all that I liked about Antonio Mairena. Regarding Antonio Mairena as a cantaor, I like everything. Particularly in what he called cantes básicos, such as the seguiriyas, soleares, tonás and the aires festeros. When it comes to the cantes de levante, malagueñas, granaínas and fandangos, I’ve always preferred other cantaores, although this master knew how to sing those palos well and recorded them. The only time I was in his house in Seville, on Padre Pedro Ayala Street, we talked about the so-called cantaores enciclopédicos and he told me that there was no such thing, that there had never been any cantaor in history who excelled in all the palos of flamenco.

I was very young, 20 years old, and I was not going to argue with one of the most well-versed flamenco artists at the time, but I mentioned Manuel Vallejo and his extensive discography, and Antonio avoided discussing that genius from Seville, steering the conversation towards Pastora Pavón as the quintessential cantaora larga, that is, a cantaora with the ability to excel in a multitude of different palos. Pastora and Vallejo not only were the cantaores with the most extensive repertoire of their day, but of all time, as attested by their discography, although Mairena put more emphasis on his cousin, Pastora.

People say that Antonio Mairena rescued many flamenco styles from oblivion, but how many others palos were rescued by those two geniuses from Seville? Can you imagine the anthology that Pastora could have left us if she had been able to, besides all she recorded on slate records? She was singing since she was a little girl and listened to most of the old great cantaores, such as Mercedes la Sarneta, Trini de Málaga, Juanaca, Paca Aguilera, Carmen la Trianera, Luisa la del Puerto and Frijones.

I liked many things about Antonio Mairena. First, his love for cante and hist great interest in learning all about flamenco»

Pastora didn’t just learn from the masters of her time, the professionals, but also from anonymous performers. Mairena once said that hers wasn’t a family of artists, but her father and mother used to sing, as well as her grandfather Tomás el Calilo, who was from the time of El Fillo and Silverio. Juan Valderrama told me that Pastora was able to sing soleares for a whole hour without repeating any style or lyrics, and she could do the same por seguiriyas and por tangos. And in Huelva she would sing fourteen different styles of fandango.

Oddly, Antonio once said that “even though she didn’t know what she sang, her voice and grace were unique”. What did he mean by “she didn’t know what she sang”? I suppose he wanted to emphasize Pastora’s very personal voice, because I can’t believe he really disregarded the wisdom of a woman who performed for seventy years and met all the great cantaores of those seven decades.

Has anyone carefully analysed Manuel Vallejo’s discography? How many anthologies he left us, in all palos? It’s true that in those days cantaores didn’t have the mindset of leaving a legacy for the future generations, and there was no technology that permitted recording fifty slate records in one sitting. But year after year, record after record, Both Pastora and Vallejo created two of the most important anthologies in cante jondo.

I liked many things about Antonio Mairena. First, his love for cante and hist great interest in learning all about flamenco. It wasn’t easy for him to become a cantaor in Mairena del Alcor, where he was sometimes heckled for having, as reliable witnesses would put it, “the voice of a calf”. He wasn’t liked in his own town, that’s the truth, except by his own family and by a handful of aficionados. The master didn’t mention this in his memoirs because deep inside he loved Mairena del Alcor, perhaps because of his family roots, which are very important for all Gypsies. He soon left his town for several reasons, living in places like Arahal, Carmona, Seville and Huelva. He visited Mairena regularly, though, where he also had a small house, and was always welcomed by the town’s good aficionados, who were mostly non-Gypsy, incidentally. Yet, he returned to his house in Seville as soon as he could, because he knew he had to build his career elsewhere, although that wasn’t easy for him either. Mairena had a very hard time in Seville, for example.

«Pastora and Vallejo not only were the cantaores with the most extensive repertoire of their day, but of all time, as attested by their discography»

When he realized how difficult it was to succeed among the great stars of his time, he focused on learning, waiting for an opportunity, and that opportunity materialized when Ricardo Molina chose to award him with the 3rd Golden Key of Cante in Córdoba, in 1962. Eight years before, he had told Juan de la Plata in an interview — the first time he was interviewed by a newspaper journalist, when he was over forty years old — that Niña de los Peines was “the only one who deserved to be awarded the Key of Cante”. Yet, when Ricardo mentioned the possibility of giving him that award, he liked the idea and forgot all about Pastora. In fact, she wanted to dispute that award, and he did all he could to dissuade her.

Mairena knew that it was his time to shine, the moment he had been waiting for so many years, and he wasn’t willing to let it pass. From having an obscure career without an interesting discography, he because the boss of cante. He didn’t create the summer festivals, but he jumped on that wagon because he knew he could stand out in that environment. Then he started to design his career in a planned and orderly manner, creating the mairenista ideology and suppressing any attempt against his dominance.

The rest is history. Antonio Mairena was the leader of cante for twenty years, leaving an outstanding discography and creating one of the best schools of cante of the 20th century. Besides, he did this in a crucial moment, when the last gasps of the ópera flamenca were seriously harming flamenco. I strongly disagree with many of his ideas and I’m not really interested in the theoretical aspects of his legacy. Yet, I admire the merit of this Gypsy from Mairena del Alcor, who had so much against him from the very beginning. That’s something that cannot be denied by the most fanatic mairenistas, who have greatly harmed and continue to harm the legacy of Antonio Mairena.

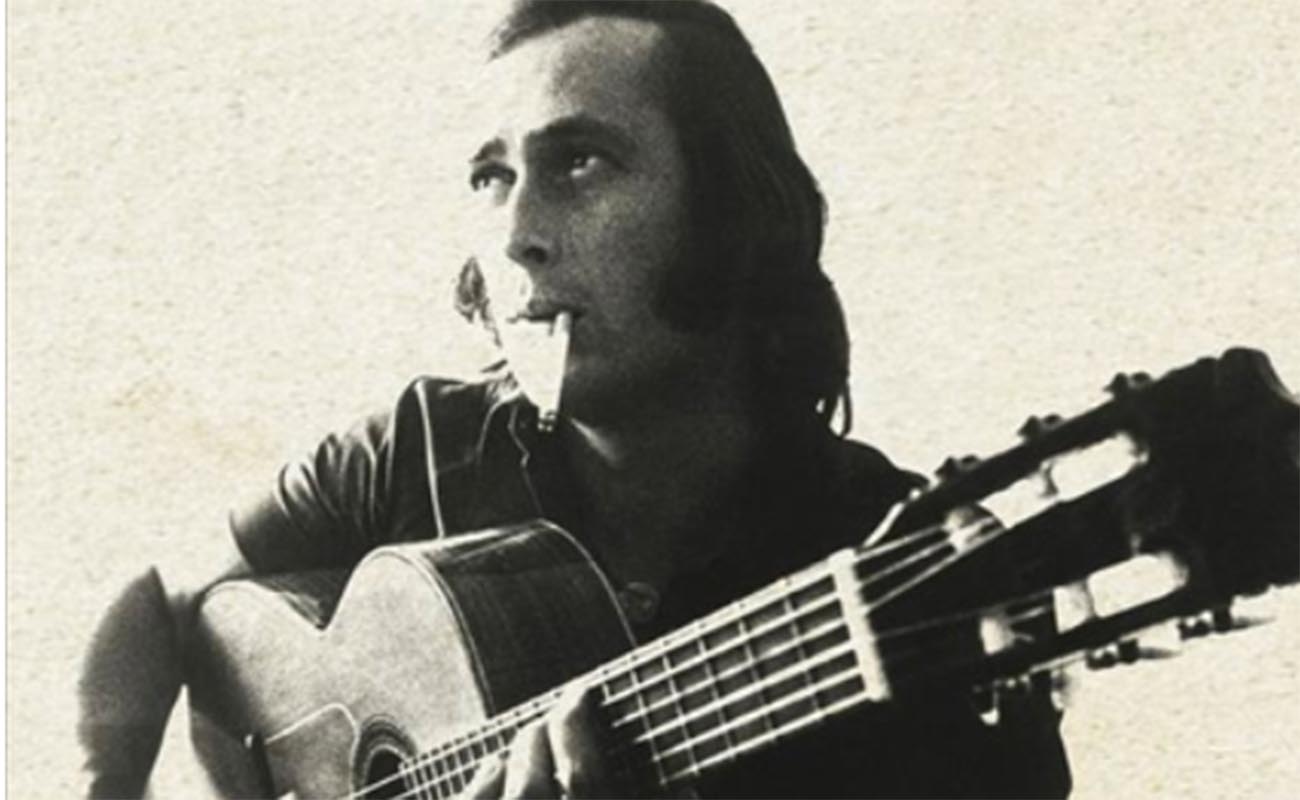

Photos of Antonio Mairena: Archivo Segundo Jiménez