The scream of Rosa Montoya

When the genius died on July 20th, 2005, Rosa felt as if she had died with him. In her mourning dress, wearing a black veil, stricken with grief, she stood by the door of the cemetery, and when she saw the hearse bringing her partner’s corpse, she screamed in a way that chilled all our hearts, Antonioooo!

There is a book that hasn’t been written yet, the one about the wives of the flamenco artists. It’s a project I’ve been keeping in a box at my office for years, a project that I shall finish one day. In my forty years as a flamenco aficionado and critic, I’ve met dozens and dozens of them, those women who are always besides the cantaores, enduring long sleepless nights waiting for their husbands, putting up with misery and want, standing by their sides at the theaters’ backstage, or humbly sitting on a wicker chair in a peña flamenca. Yet, they don’t show up in any albums’ credits and are seldom mentioned in the artist’s bios.

I’m thinking about the wife of Juan EL Pelao, Clara, niece of La Adonda, who when the martinetero from Triana refused some coins gifted by general Sánchez Mira at the end of a party, had to tell her husband “Take them, Juan Pelao, that I have nothing to cook for tomorrow!”. I’m also thinking of Reyes Bermúdez, the wife of Tomás Pavón, ironing his best shirt for his performance before Luis el de la Loza at La Europa café, so they could have something to eat the next day. I’m thinking, too, about Rosa Montoya, the wife of Antonio el Chocolate and sister of the great Farruco, looking at him, enthralled, as he was telling a story from his childhood, when he was hired to sing fandangos at the San Fernando de Sevilla cemetery by a distraught señorito from Macarena whose mother had passed away.

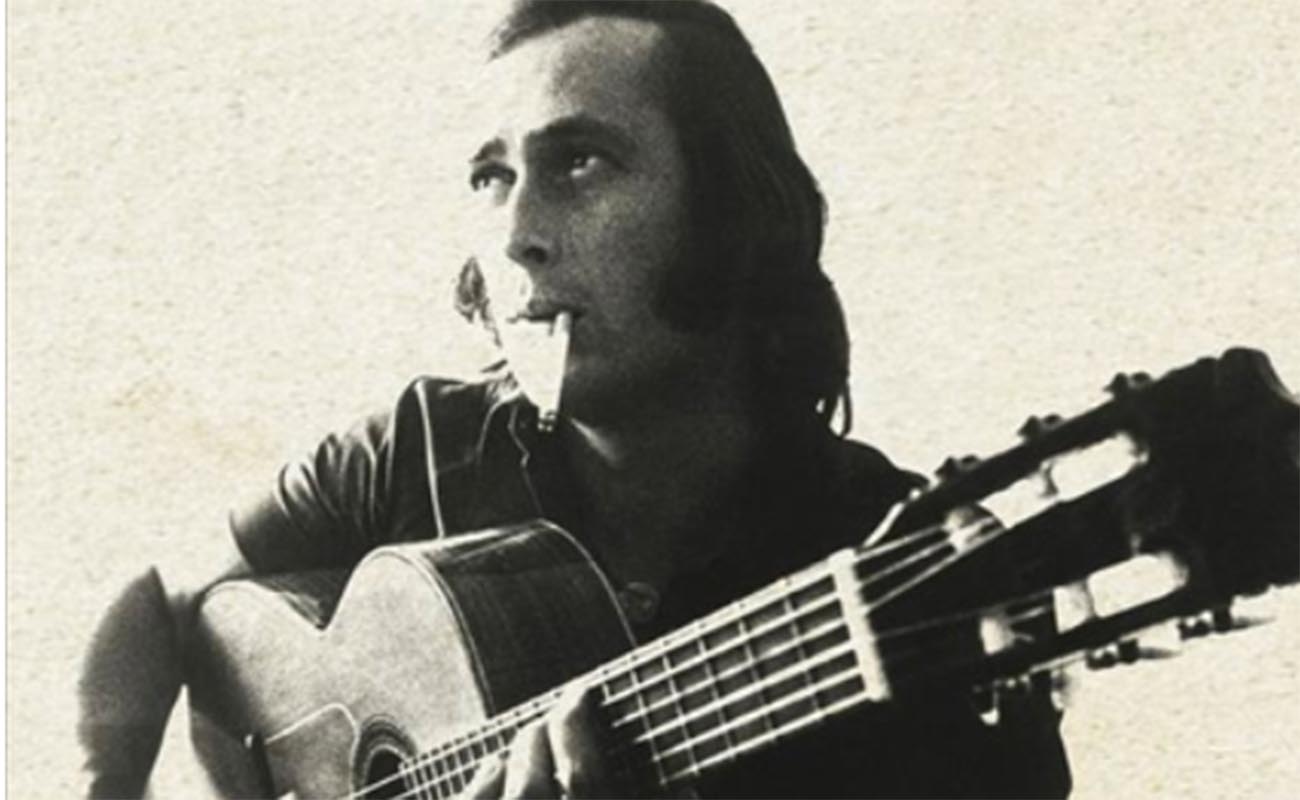

Rosa Montoya Flores, Chocolate’s wife, a Gypsy who seemed to have come straight out from an engraving by Gustave Doré, was Antonio’s greatest supporter, his wife, friend, adviser and, sometimes, more mother than lover. Chocolate was a very unconventional Gypsy, good-looking, very fond of partying, lover of good wine and not good at making money. At the beginning of his career, he would sometimes go to the towns’ festivals on a motorcycle, and Rosa would tie up on the bike’s rack a small plaid suitcase where she would put his suit and shoes, and sometimes a piece of cod to clear up his voice and a flask with scotch whisky so he could warm up his dark throat in the cold nights of the hillside towns. They didn’t have children, but they had each other and were madly in love, although they had their fair share of arguing, too. I was at their place the day before the death of the cantaor, when I had to kneel down to give him my farewell, as he didn’t have enough strength to get up from the sofa. I looked at Rosa Montoya’s eyes, and they were overflowing with anguish, helplessly witnessing her beloved man and cantaor dying, unable to do anything about it, facing a life alone in that small flat in Seville, near La Macarena, full of memories, awards and pictures on the walls. When the genius died on July 20th, 2005, Rosa felt as if she had died with him. In her mourning dress, wearing a black veil, stricken with grief, she stood by the door of the cemetery, and when she saw the hearse bringing her partner’s corpse, she screamed in a way that chilled all our hearts, Antonioooo!

Flamencologists have been for centuries trying to find out what’s the origin of Gypsy seguiriyas which, according to Lorca, have an irrational rhythm. Rosa explained it in six seconds, which is how long that scream lasted, certainly shaking the bones of all the Gypsy seguiriyeros buried in that graveyard in Seville, from Paco la Luz and Manuel Cagancho to Manuel Torres and Tomás Pavón. Rosa couldn’t take it any more, and she exploded, letting out all her pain, not only with a terrifying scream, but also, like Almeria’s poet Rafael Sánchez Segura would say, with the scream’s pain.

¡Ay, te traga la tierra,

me dejas aquí!

Sin el consuelo,

de tus ojitos negros,

¿qué será de mí?