The girl from Argentina who dreamed of Seville

I have been for many years in this flamenco world, and I have never come across a book like this one written by La India, a work of great tenderness that has a perfect symbiosis of teaching and flamenco soul.

I have wondered many times if I would be able to abandon my country, my city, my people, my home, and being so strongly in love for one art that I would actually make the move. I have always answered myself that no, that nothing and no one would be able to uproot me from the land of my ancestors, from my land. That is why I admire so much those who are able to do it, those who one day see one star and follow it, wrapped in uncertainty and doubt, yet full of illusions. In the world of flamenco it happens frequently that human beings from other lands one day discover the magic of one artists, or the magnetism of one cante, and they leave everything to come to this land that have given the world plenty of both. It was already happening in the XIX century, when flamenco was just a project of universal art. I don’t mean the romantic travelers that came on their own and went back to their countries to write a book that seldom reached Andalusia. I mean people that one day, in their country, discovered La Cuenca or Antonio el de Bilbao in a theatre and reached the strange conclusion that a life far from them or their land had no longer any meaning. This is what happened to María Virginia Di Domenicantonio, La India, a beautiful and intelligent Argentine bailaora that felt drawn to Spanish dance in her hometown, La Plata, when she was only 6 years old. If in this day and age people are still surprised that there is a flamenco festival in Pamplona, just imagine what they would think about a girl from Argentina feeling the call of this Andalusian art.

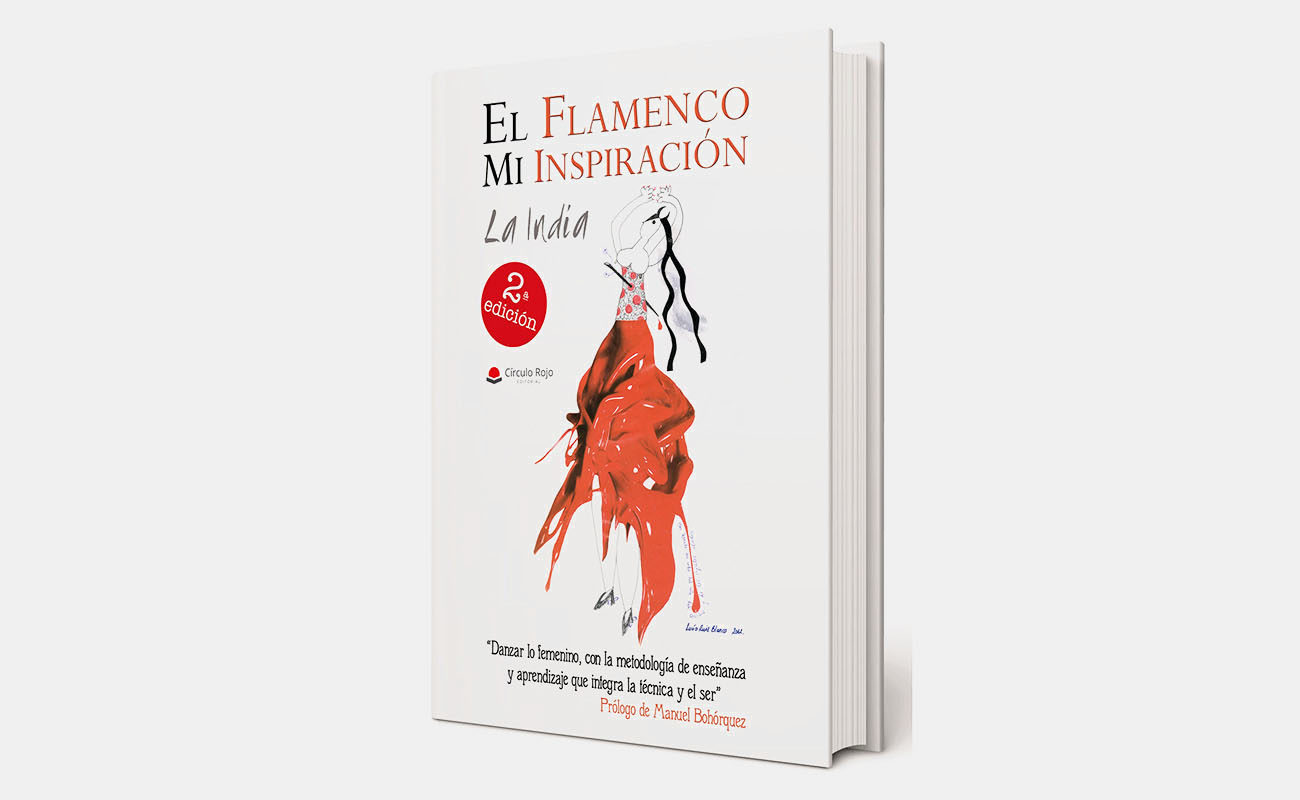

As if for the Argentinians, especially those from Buenos Aires, flamenco was some strange art, something from another planet. Andalusian people believe in the universality of the arte jondo, yet they think it’s strange that a Japanese would be able to feel cante, not to mention perform it. La India learned flamenco in her land, with Spanish instructors that traveled to Buenos Aires to perform and teach. She also became a physical therapist. She would come to Andalusia as often as she could, something complicated by the high cost of the long trip. Jerez and Seville were her favorite places, so she could learn in flamenco’s “cradle”. That gives us an idea of what she was looking for: the essence. It doesn’t mean that Granada, Córdoba or Almería lack flamenco essence, she just knew where was the essence she most cared for. Interestingly, she chose to learn from a multitude of different artists. She could have chosen Matilde Coral or Angelita Gómez, the essences of Triana and Jerez, respectively, but she widened her choices admirably. She was looking for a good training, not to be the replica of any teacher or artist. She succeeded. In July 2007, she decided to leave La Plata and settle in Seville, knowing well it would not be easy to make a living as a professional bailaora. She has been almost eight years in Seville, and not only she has managed to make a living from baile as performer and teacher, making her dream come true, but has now written a beautiful book, El flamenco, mi inspiración, In in which she has tried, with great success I would say, to describe the instructor-student relationship, without creating an unbearable theoretical treaty, but something rather delightful, with soul and a huge dose of sensibility.

I have been for many years in this flamenco world, and I have never come across a book like this one written by La India, a work of great tenderness that has a perfect symbiosis of teaching and flamenco soul. It is not a book for learning how to dance or move your body as best as you can. Rather it’s a book about the love for this art, about making discipline, willpower and perseverance more than just tools, about enjoying the journey of learning about our bodies and learning about flamenco art itself, which is what moves the body. I have to confess that by reading this book I have discovered things I didn’t know about flamenco teaching. I’m friends with all teachers in Seville – I was friends with Enrique El Cojo, Pepe Ríos and Morilla – and by reading this book with enthusiasm, I am sure that I will value even more those who perform this great job of instructing, be them Andalusians by birth or not. The success of that girl from La Plata, who dreamed of Seville when only 6 years old, is something that, as a sevillano, gives me overflowing satisfaction. As Luis Caballero used to say, flamenco is more than just wine and song. Never doubt it.