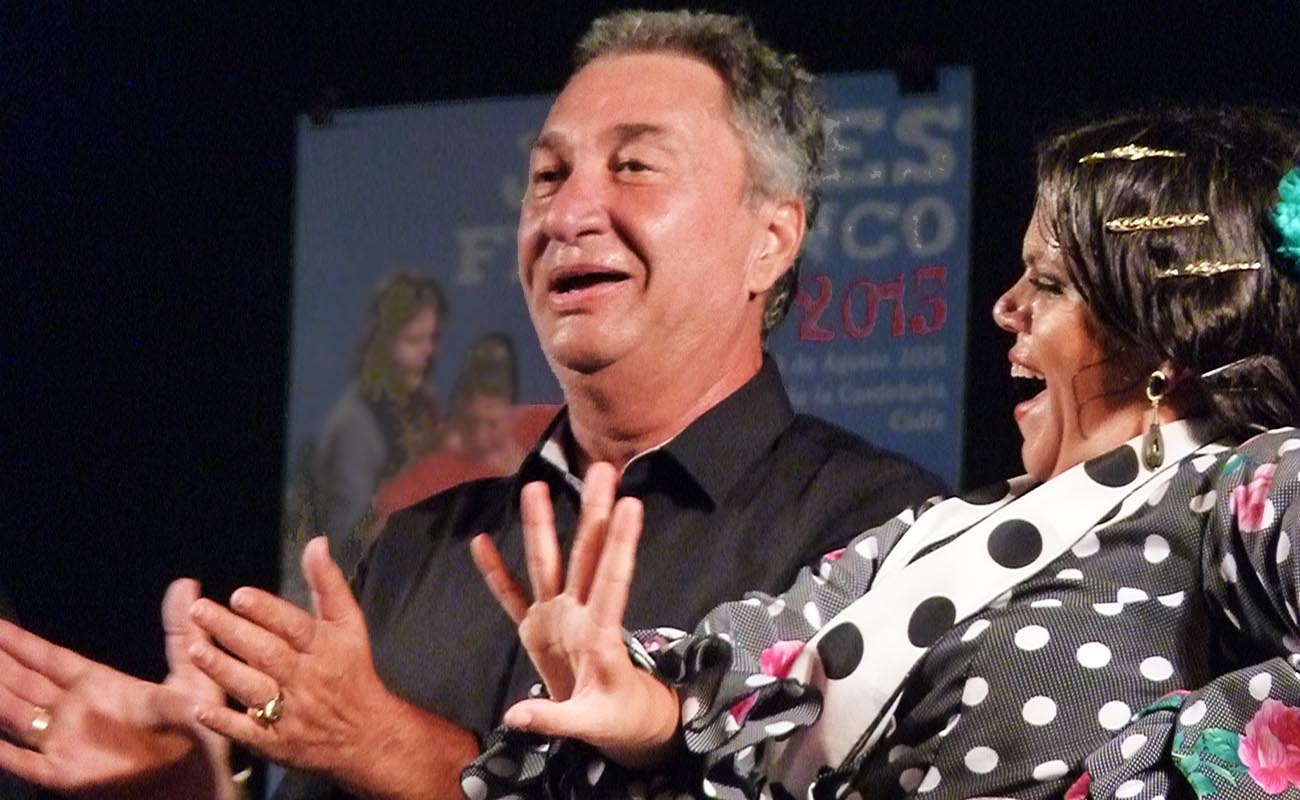

Miguel Funi, Lebrija’s Giralda

Miguel Funi is a cantaor, not a bailaor, although he combines both, as it was traditionally done in the gipsy parties of his childhood in Lebrija, and it was in these family parties where he learned everything, although he also learned from great stage artists that weren’t from Lebrija

Just yesterday, I had a long conversation with Miguel Funi, cantaorand bailaorfrom Lebrija, and I was amazed how well his mind works, despite the fact that he’s no longer a child. He’s one of the more sincere flamencos I’ve ever met, and in forty years I’ve met them all, from the greatest to the humblest. Miguel may have his defects, like we all have, and some may like him more than others, but he’s an upright man who doesn’t mince words, and that sometimes has got him in trouble with friends, critics and aficionados. He’s the kind of flamenco artist who, when they pass away, everyone says they were a genius, but by then it doesn’t matter. The important is to say it when the artist is alive, and to help him survive in a small world that is sometimes unfair. While Miguel is an artist who still works and has recognition, we haven’t made the most of the fact that he is a gipsy cantaorfrom the old school of Lebrija, who has wisdom and life experiences that few people of his generation have had. In any place other than Andalusia, he would be a cherished artist being invited to theatres and universities all over the country as a guest speaker to tell of his life experiences. Also to sing and dance, of course, because he still does both with talent and lots of art.

Miguel Funi is a cantaor, not a bailaor, although he combines both, as it was traditionally done in the gipsy parties of his childhood in Lebrija, and it was in these family parties where he learned everything, although he also learned from great stage artists that weren’t from Lebrija, from cantaores such as Mairena or Caracol, among others. However, Miguel never wanted to leave Lebrija, despite having had opportunities of settling in Madrid or Seville, the places where all artists went. El Funiis from Lebrija, and he can only live in his own hometown, walking every day on its narrow cobblestone streets, among its whitewashed houses, talking about cante in its taverns, breathing the marshland air and smelling the perfume of the flowers and olive trees. Miguel is also an artist who suffers because he disagrees with the way cante jondois going these days. He agrees that there are good artists with good voices, but he laments the lack of a good fan base and the lack in artists’ personality. Naturally, Miguel belongs to another era, when youngsters looked up to the old masters to learn from them in parties and gatherings, instead of learning from recordings. He gets thrilled when talking about Mairena, Juan Talega, Perrate, Diego del Gastor, Caracol, Paco Valdepeñas, Fernanda, Bernarda or Ansonini del Puerto. He talks with respect about other artists he didn’t grow up with, such as Pepe Marchena, with whom he worked while that cantaor was near retirement. It’s not acceptable that we’re not making the most of a cantaor like el Funi, because there are not many artists like him left. Very few young artists sing and dance at the same time –Luis Peña and Javier Heredia stand out– and the few who do, follow their own school, or the style of Paco Valdepeñas, because few of those who sing and dance today can match Ansonini. Miguel is from that school, one of the few left. His voice is still fresh and powerful, and his dancing style has a character that takes you to another era.