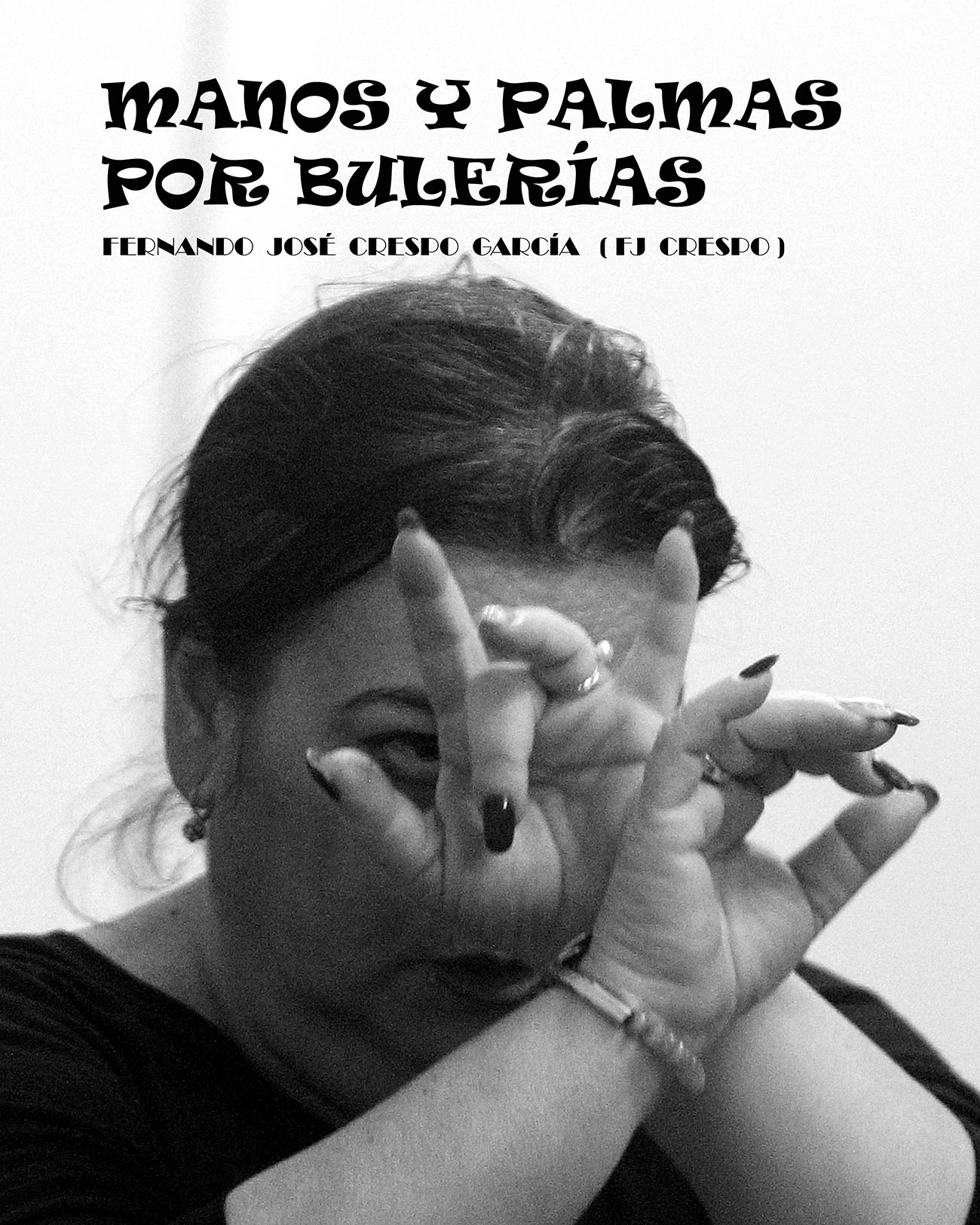

Fernando Crespo, capturing compás

He has created this wonderful photographic work, 'Manos y palmas por bulerías', like a movie director who carefully choses locations, backgrounds and lightning before starting to film his masterpiece. He has been able to see what can only be felt.

For starters, I have to admit that when Fernando Crespo called me asking me to write the prologue for his book about flamenco photography, Manos y palmas por bulerías, since I was in the midst of moving houses are very burned out, I almost wished he changed his mind and asked someone else, despite the fact that I’ve always admired him as a photographer and great professional of photojournalism. He has photographed lots of famous flamenco artists and I’ve seen photos by him that have filled me with envy, and not in a good way.

I really envy Fernando’s technique and vision, because I also take flamenco photographs and I must have thousand of black and white negatives from the time I covered the summer festivals for El Correo newspaper and no photographer would come along. Thus, I have reasons to admire this man and envy him insanely, perhaps because in fact I’m a frustrated photographer, just like I’m also a frustrated cantaor who became a flamenco critic out of a bit of revenge. I cannot be like you guys, geniuses of cante, so I just criticize you and that’s about it. So here I am, a bully full of complexes.

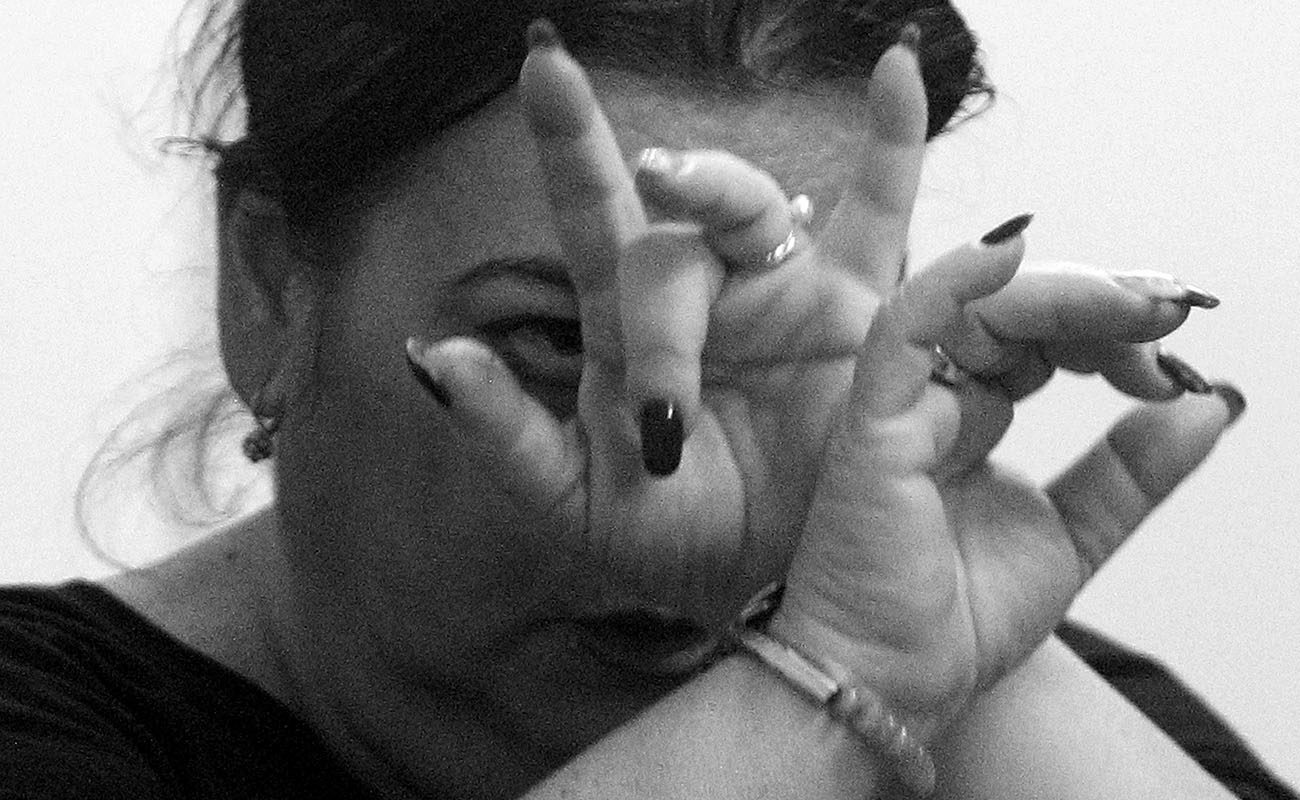

After taking a closer look at all the photographs of this beautiful and original flamenco book, I must highlight the fact that I know none of the subjects in any of the black and white images, who are mostly women trying to learn to dance por bulerías, the most difficult palo in cante jondo, because trying to dance bulerías without a good sense of rhythm it’s like trying to play tennis without arms. That’s where I stopped and got really interested in this innovative work, whose author plays with compás as the best specialized cantaor and dares to stop it, to freeze it, without ever messing up the image. These are seemingly easy, simple photographs, but that’s not the case. It’s not a matter of freezing an image, but of knowing when to freeze the compás while also capturing the expression of the one singing or dancing before it’s no longer interesting and avoiding the metric to come out as cold and mathematical.

If each one of these photographs, all eighty of them, could be put in motion with some mechanical device, we could feel we’re inside a practice room feeling the compás, that un, dos, tres, cuatro cinco, seis, siete, ocho, nueve, diez…, un, dos…, where we could fit a whole theory about the fiesta flamenca. Gestures, looks, poses which seems as if they had their own music, or invite the readers to create their own. Flamenco is very photogenic, and sometimes we may accidentally press the shutter button and create an unexpected masterpiece, although blurry. Yet, Fernando has created this wonderful photographic work like a movie director who carefully choses locations, backgrounds and lightning before starting to film his masterpiece.

Looking at this book in its entirety, from the first to the last image, we end up understanding that sometimes duende is not in the artist, but in the spectator who knows how to feel it. Fernando has been able to see what can only be felt.