A conversation with Camarón

The only way to remain in my old profession as a flamenco critic is getting now and then into those gatherings of aficionados and professionals who like to get in the party, singing without a guitar and keeping the beat knuckling on a table or on the bar’s counter.

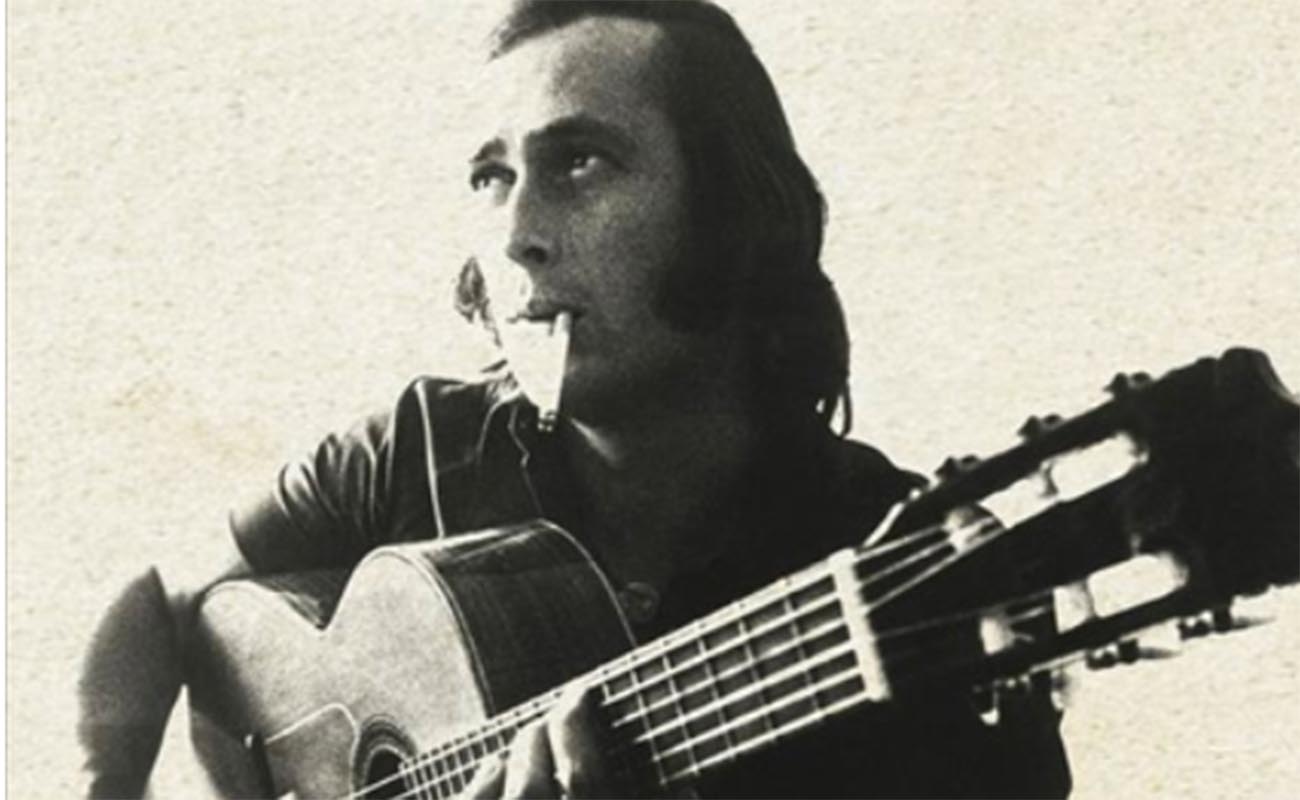

These days I’ve been thinking about the emotion we feel when we listen to flamenco, and about how our knowledge of this art affects that emotion. I didn’t have many conversations with Camarón de la Isla, maybe two or three. One of them was in Montreux, Switzerland, when we were joined by Quincy Jones, the great American musician and producer, who that night was enthralled by the Gypsy cantaor. Talking about the emotion felt while performing or listening to cante, Camarón said something that struck me: “I don’t feel as much emotion now as I felt at the beginning of my career, when I would hear an aficionado singing in a tavern and my eyes would well up with tears”. Quincy Jones nodded in agreement when the translator conveyed the words of José Monge1, and I got chills, because I felt the same way as the genius.

When I was a teenager, when I started to develop an interest in cante, I remember listening to aficionados at gatherings in the taverns with tears rolling down my cheeks, overcome with emotion, not yet knowing if they were singing properly or not, not knowing if they knew what they were doing or if they were mixing up seguiriya of Paco de la Luz with another of Viejo de la Isla. I remember thinking to myself “if I cry like this now, knowing nothing about cante, I can only imagine how much I’ll cry when I understand it better!”. Yet, I haven’t cried more, not at all, perhaps because being a flamenco critic has hardened my heart, after having studied so much cante and so many cantaores. Maybe it’s also due to the fact that, when I get on my seat in a theater to listen to a performance, I do it more to analyse how it’s done, and not to appreciate how the performance is felt and lived, which is what impressed me the most, forty years ago, when I would get the shivers listening an aficionado sing a fandango de Caracol in some bar. I talked about this with Camarón that night, and he said that he felt the same way, and that because of it he always tried to spend some time with aficionados, in bars or in peñas. “I like picking up the guitar and accompany aficionados who may be out of tune, but who sing with their whole soul”, he said.

A few days ago I was in Mairena del Alcor in a gathering of cantaores, good ones, who not only perform on stages but also partake in bars. I felt so much emotion that I started singing, which is something I don’t do often. I needed to get out all the emotion I felt when listening to these pure and humble small-town cantaores, who sing with all their heart and soul, without trying to impress anyone. Cantaores that throw their cante in our faces, because they’re so close to us. In theaters, there is always this sort of “invisible barrier” separating us from the cantaor. Professional cantaores must provide a minimum standard of quality, so, before getting on stage, they’ll check the sound system, the lightning and all those technical details that do not exist in gatherings of aficionados or in private parties, where everything is simple and natural.

Camarón told me a story from the time he was very young, when he was in a private party where Caracol was singing. The master sang exceptionally well, giving it all, with no mic or any sort of technical resource, having had quite a few drinks, too. Camarón was thrilled to be in the company of the old Gypsy from Seville, and made a comment about the cante he had just heard. Manuel Ortega2 told him: “It is here where you should learn. The tricks are for the theaters.” I have thought about that, these days. About how the emotion of listening to cante diminishes as we widen our knowledge about cante and cantaores, learning about their tricks and cheats.

The only way to remain in my old profession as a flamenco critic is getting now and then into those gatherings of aficionados and professionals who like to get in the party, singing without a guitar and keeping the beat knuckling on a table or on the bar’s counter. Going back to flamenco’s roots is not just studying the old shellac records, but finding the emotion in the cantaor who sings for himself, and not for a public that typically knows little about this art.

1 José Monge Cruz, “Camarón de la Isla” (sometimes spelled Monje)

2 Manuel Ortega Juárez, “Caracol”

This article was originally published on December 16th, 2015