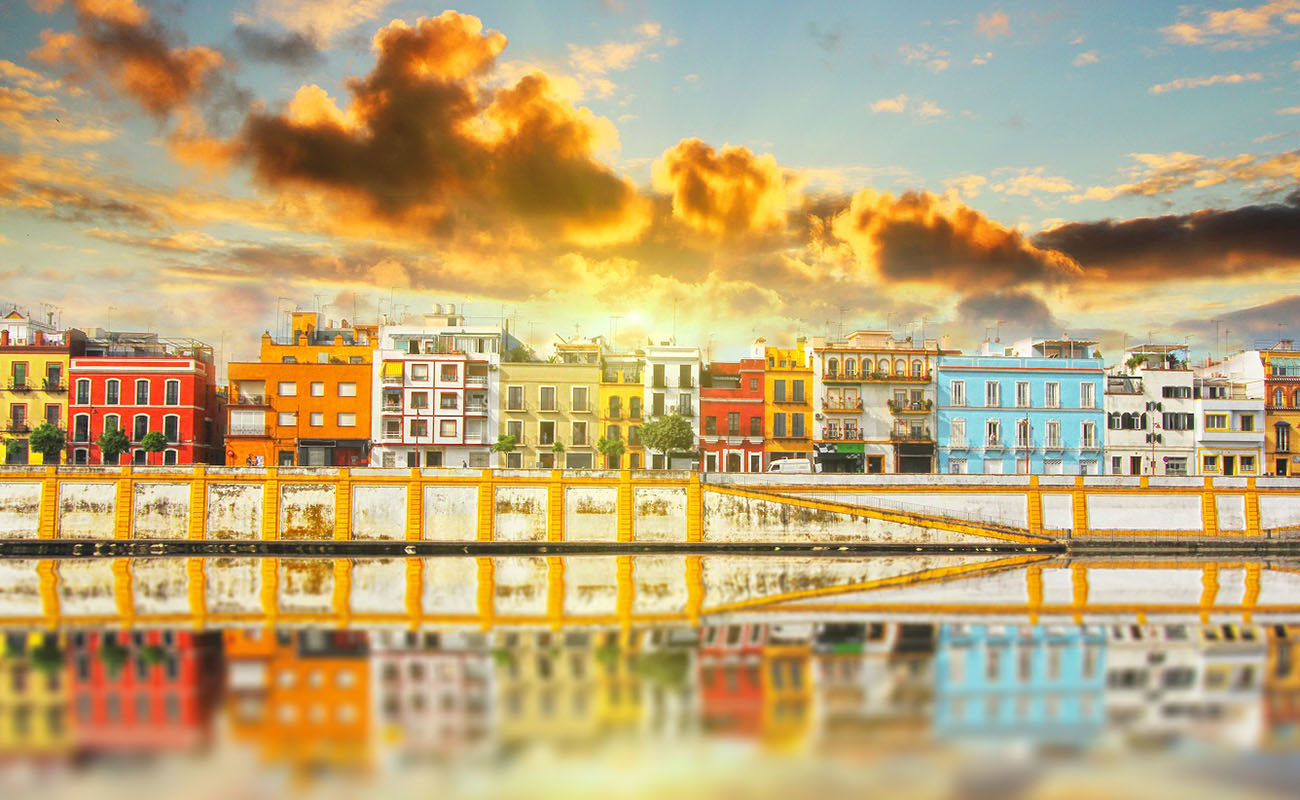

Triana, between yearning and oblivion

Last Saturday I was in Triana on occasion of its renowned Velá de Santa Ana celebrations, and I went for long walks on those narrow streets that I like so much. I remembered one night when the great bailaor Manuel Corrales González El Mimbre (brother of Matilde Coral) told me at Taberna El Altozano that I would never be a true trianero. I didn’t refute this, but

Last Saturday I was in Triana on occasion of its renowned Velá de Santa Ana celebrations, and I went for long walks on those narrow streets that I like so much. I remembered one night when the great bailaor Manuel Corrales González El Mimbre (brother of Matilde Coral) told me at Taberna El Altozano that I would never be a true trianero. I didn’t refute this, but it hurt, because I worked in Triana since I was just 13 years old and from those days until now I’ve always been connected to that district, having been married at Capilla de los Marineros (the headquarters of the Esperanza de Trianabrotherhood) in 1986 and having lived in Triana for eight years. Yet, people don’t become trianero for having been married in Triana or for having lived in that district for many years, but for wanting to be trianero, and whenever I go to that district I feel that I belong to it.

When I started visiting Triana in the 1970s, the scent of flamenco was everywhere, and I had the privilege of meeting many flamenco artists that are no longer with us. I often went to El Morapio, for example, and chatted with the old flamencos who already yearned for the more genuine Triana. A few days ago, I had a small discussion with a good aficionada who lives in that quarter (on Pureza street, I believe) and she lamented that Triana didn’t have a museum or an archive centre, among other grievances unrelated to flamenco. She put the blame on the politicians, but the ones to blame are the people of Triana themselves. Let me explain.

Triana is essential in flamenco history due to the many flamenco artists who were from that district, and particularly due to the many styles of seguiriyas, soleares, tonás, tangos, romances and bulerías that originated there. There is no doubt that there’s a school of cante and baile from Triana, yet this district has never had any reputed flamenco historian able to demonstrate its importance, as has been the case with Cádiz, Jerez, Córdoba, Málaga and Huelva.

Likewise, the people of Triana has never had any interest in those outsiders, like me, who have bothered to research flamenco in that quarter. I myself have been researching this art in Triana for twenty years and I’ve earned nothing but criticism. It’s been years since I last said anything about flamenco in Triana, although I have a lot to say about its 19th-century artists. I also have a lot to refute, which is something the people of Triana doesn’t like to hear because they like to believe that flamenco was invented there and that all the great flamenco artists were from Triana, which is not true.

Triana should start by commissioning a serious research about the history of flamenco in that district. A team that can get to work right away, but with a budget provided by the City Council or by the Junta de Andalucía. I volunteer to lead such team, although I don’t have much spare time due to my multiple occupations. When the work is completed, all the material gathered should be hosted in a good archive centre available for academics, artists and aficionados. Would any institution of Seville be able to afford such undertaking? Definitely yes, because a lot of money is squandered in many other things.

In two or three years, for example, Triana could have that great flamenco archive center and museum. Yet, in order to achieve this, we must get to work, instead of ranting in taverns. And we must be willing to accept the findings of such research, which will reveal uncomfortable truths.

If Triana wants, we are willing to help. Selflessly, by the way, although if there isn’t a budget set aside for this adventure there is no point in even talking about it.

Translated by P. Young