The Ópera Flamenca in Jerez in 1928

In 1928, the agent Vedrines undertook a wonderful entrepreneurial adventure for that time: creating a show with the most famous stars in those days, even as there were noteworthy absentees in the lineup, such as Manuel Torres, Niño de Marchena, Niño de Caracol, El Cojo de Málaga and other leading artists. However, this renowned agent managed to convince Don Antonio

In 1928, the agent Vedrines undertook a wonderful entrepreneurial adventure for that time: creating a show with the most famous stars in those days, even as there were noteworthy absentees in the lineup, such as Manuel Torres, Niño de Marchena, Niño de Caracol, El Cojo de Málaga and other leading artists. However, this renowned agent managed to convince Don Antonio Chacón to do the tour, something that was not easy at all for him, but this genius needed the money. The maestro from Jerez headlined this tour, Solemne Fiesta Andaluza (“Solemn Andalusian Party”), shared with Niña de los Peines, Manuel Vallejo, José Cepero y Guerrita, a veritable idol of the masses at that time. El Chato de las Ventas, Bernardo el de los Lobitos y El Niño de Sevilla also featured, joined by four leading guitarists: Ramón Montoya, Luis Yance, Manuel Martell and Manuel Bonet. Performing baile were Carmen Vargas, El Estampío, Frasquillo, his wife La Quica and Carmelita Borbolla. There was also an act was by Los Seis gitanillos de la Cava de Triana(“The Six Little Gypsies from Cava de Triana”), who were quite an spectacle of Gypsiness and compás.

After touring in several big cities with great success, thousands of people attended the performance on August 4, 1928 at Jerez’s Plaza de Toros (bullfighting ring, also used as a venue for other shows and performances). The newspaper El Heraldo de Madrid assigned Guillermo Espejo to write the review, who wrote at length about the artists and left a flamenco critic in the historical archives worthy to be analysed by ExpoFlamenco readers. It’s rather long, but don’t miss any detail because it’s quite interesting:

Wholesale ‘cante jondo’

Jerez has given it all this evening in August. Already some boisterous posters with pictures, full of outlandish adjectives and interjections, managed to excite the core of emotional people, who in this town is basically everyone, some more than others. If Alcalá is the town of almonds; if the best mostachones are from Utrera; if the best butter cookies are from Antequera and Astorga; if Logroño makes the ultimate canned fruits in all Spain, the best asparagus and strawberries are from Aranjuez, and Albacete is renowned for its razors and Trubia for its cannons, then here in Jerez, besides being famous all over Spain for its wines and its horses, we have the key of “cante jondo”. Among the people of Jerez, the few who doesn’t actually know how to sing flamenco, definitely feel and understand it. Everyone here is born a flamenco aficionado.

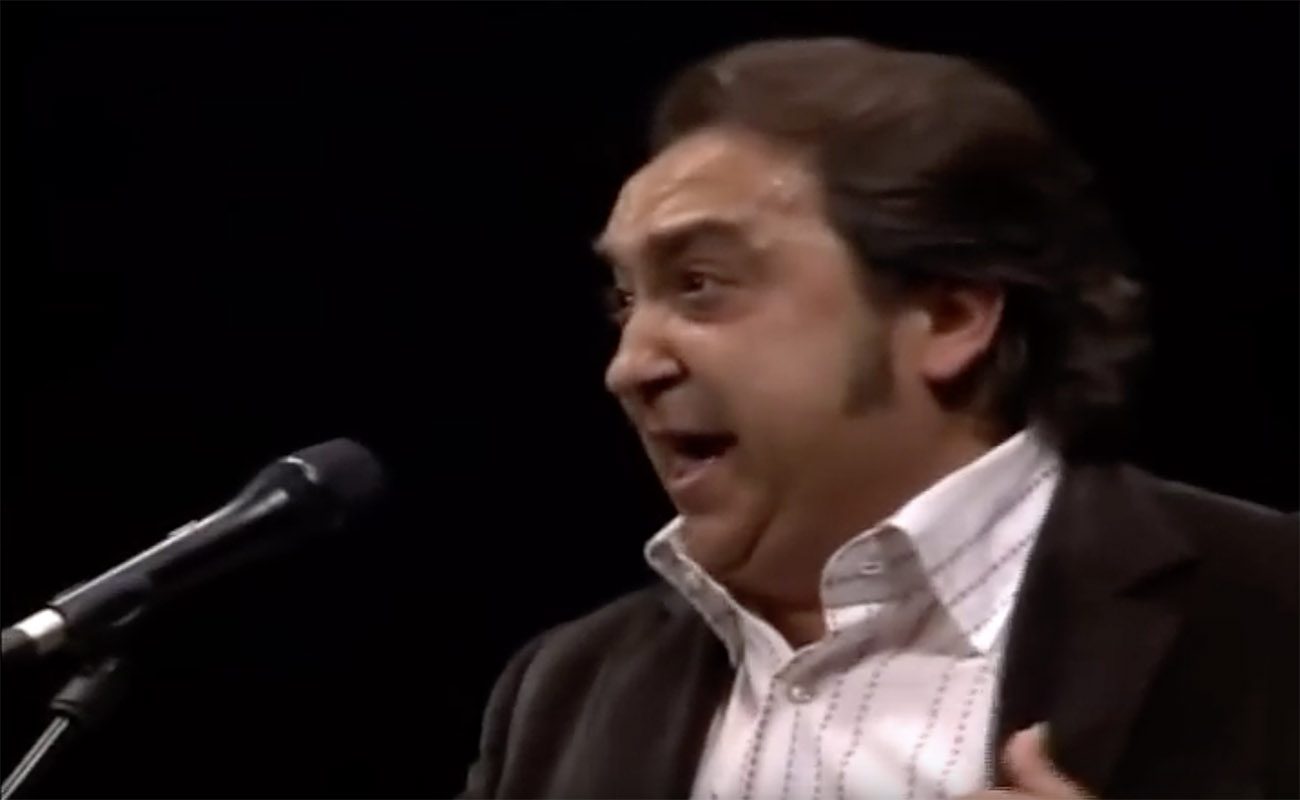

Thus, it comes as no surprise that, in this warm summer night, with unprecedent expectation, we all happily gather in our bullfighting ring to fill it up and enjoy the delight of an intimate show focusing on nothing more than Gypsy music. The rebellious guitar notes which pinch the emotions, and the voices emanating from those privileged throats which move people to tears, are the main dishes awaited with faith and gluttony, when the dinner guests are hungry and devoted. It would be impossible to gather artists of greater quality or authority. The great Chacón, who in the posters was simply referred as Don Antonio; the mischievous Vallejo, who has revolutionized the enjoyment of flamenco in Spain with the gramophone, and referred in the show’s posters as the human nightingale; Cepero, the poet of flamenco cante; the virtuous Pastora, who doesn’t like being Gypsy or being referred as “Niña de los Peines”; one Guerrita, who despite not being flamenco or looking like one, sing what they do and is known as King of Cartageneras; various “niños” who aren’t such thing since long ago., and a Chato de las Ventas, the only one whose stage name immediately makes sense when we notice his flat nose, were those who in this temple of bulls in Jerez de la Frontera glorified the most difficult of all cantes, judging by the efforts and contortions of its performers.

The cast was completed by renowned guitarists (Montoya and Monet among them) and a bunch of 14 bailaores of both genders and all classes and ages, some of them reportedly taken from the most ancient Gypsy traditions of La Cava and Albaicín itself. This show started exactly just like any other show in Spain (with the exception of our bullfights), with a delay of several hours. There were three hours of moans and groans, constantly interrupted by the cheering of enthusiastic aficionados, who in my opinion were very rude for voicing their loud approval before the ending of the verses. Cepero was poetic. His lyrics are truly distilled poetry. Cepero, who is from Jerez, performed local styles from his repertoire, and naturally the locals who idolize him cheered him wildly, making him sing at his best. The nightingale wasn’t fortunate with his trills. He didn’t live up to his fame and moved no one. He sang dispirited. Maybe he’s moulting?

La Niña, Pastora, brought up old tunes that made us feel young again: old and very Gypsy tangos, those which we all have listened to, when we were children, badly or worse, from our cooks. By popular demand, she got entangled with a very long seguidilla, those beloved by partying drunkards, and they’re very suitable for keeping the beat knocking on tables.

A thick man sweating profusely, seated next to me, tells me that keeping the rhythm is extremely difficult, and that in Jerez very few people know how to do this por seguidillas. I just nod with my head, without any hint of violence.

“Don’t you agree with me?” he asks, observing my comfortable silence, and perhaps hoping to have a little argument.

“Yes sir, absolutely… I fully agree”.

Who on earth dares to argue with full-blooded jerezanos, as they are the ones who have the key of cante?

Guerrita was admirable and greatly cheered. That kid has a powerful, pleasant and well-tuned voice. Yet, the people of Jerez say that what he sings is not flamenco. “We did it!”

The bailaores invaded the big stage, occupying it all, and we got the most artistic kicks. One, two…, five…, eight.. All the way to fourteen! Poor planks! Six miniature Gypsies, prototypes of that pharaonic race, with their twelve feet, rolled on that giant drum made of thick wooden planks, creating a cloud of dust and splinters. In seems to me that these half-dozen kids will get old without progressing in their art. We’ll always see them doing the same thing. The poor things are just starting their careers. They look shy, with their serious, dark and shiny faces, their bodies sickly and scrawny like human slugs. Anyone would think that instead of being from La Cava, they were taken from under a flowerpot instead.

The most beautiful Gypsy on earth, Carmen Vargas, with her beauty enhanced by a woman’s dress of the kind no longer worn by women, painted on stage beautiful shapes, all of them worthy of entertaining the best of brushes. A slender, pretty woman with big dark eyes, without lipstick and gracefully arranged hair, toped with a Spanish peineta and a flower, is something uncommon these days. Carmen Vargas’ body, fully wrapped on a white, bata-de-cola dress, with lots of lace and frills, is a national monument. For the record.

As we braced for the arrival of dawn, the crowning moment came in the form of the patriarch Don Antonio. His respectable age, his lineage and his brilliant career managed to protect him from the unleashed intelligence of a demanding public.

“Caracoles… caracoles!” demanded Chacón with a loud, desperate voice, as if asking for help.

“Let’s go, let’s go… al café de La Unión, que es donde para Cúchares y el Tato y Juan León!”, ordered don Antonio, choked up and violently hitting the stage with his walking stick. Those old cantaores can be really weird! Just imagine, performing before six or eight thousand spectators in a café in Madrid!