The new flamenco cross-pollination

The different schools of flamenco’s cante, toque and baile were formed in the 19th century as the result of the intermingling of artists from all provinces of Andalusia. It’s not by chance that Seville has a long tradition in malagueñas. That’s due to the many performers of that palo who came from Málaga and its cafés cantantes, such as El Canario and El Perote de Álora, and later with

The different schools of flamenco’s cante, toque and baile were formed in the 19th century as the result of the intermingling of artists from all provinces of Andalusia. It’s not by chance that Seville has a long tradition in malagueñas. That’s due to the many performers of that palo who came from Málaga and its cafés cantantes, such as El Canario and El Perote de Álora, and later with geniuses such as Chacón and Fosforito, each of them with a different style of malagueña, who had a rivalry in Seville in the late 1800s. And let’s not forget Juan Breva, La Trini and La Rubia. It’s also impossible to conceive flamenco in Triana without the cantaores who came from Cádiz and either settled or often visited that old district of Seville, such as El Planeta, Frasco el Colorao, El Fillo, Curro Pabla, Tomás El Nitri, María Borrico, La Sarneta and Frijones.

In baile, the same happened. Seville was already a Mecca of bailein the first half of the 19th century, having world-famous bolerosand boleras, but when Silverio and El Burrero started to work in Seville’s café cantantes (besides Juan de Dios Jiménez, son of Juan de Dios El Isleño, who managed El Filarmónico café), bailaoras from Cádiz started to arrive, such as Rosario La Mejorana, Gabriela Ortega, Coquineras del Puerto, La Malena and La Macarrona, as well as bailaores such as El Raspao and Ramírez, and that was the beginning of the famous Seville school of baile, which up to then existed in a pre-flamenco or bolero stage.

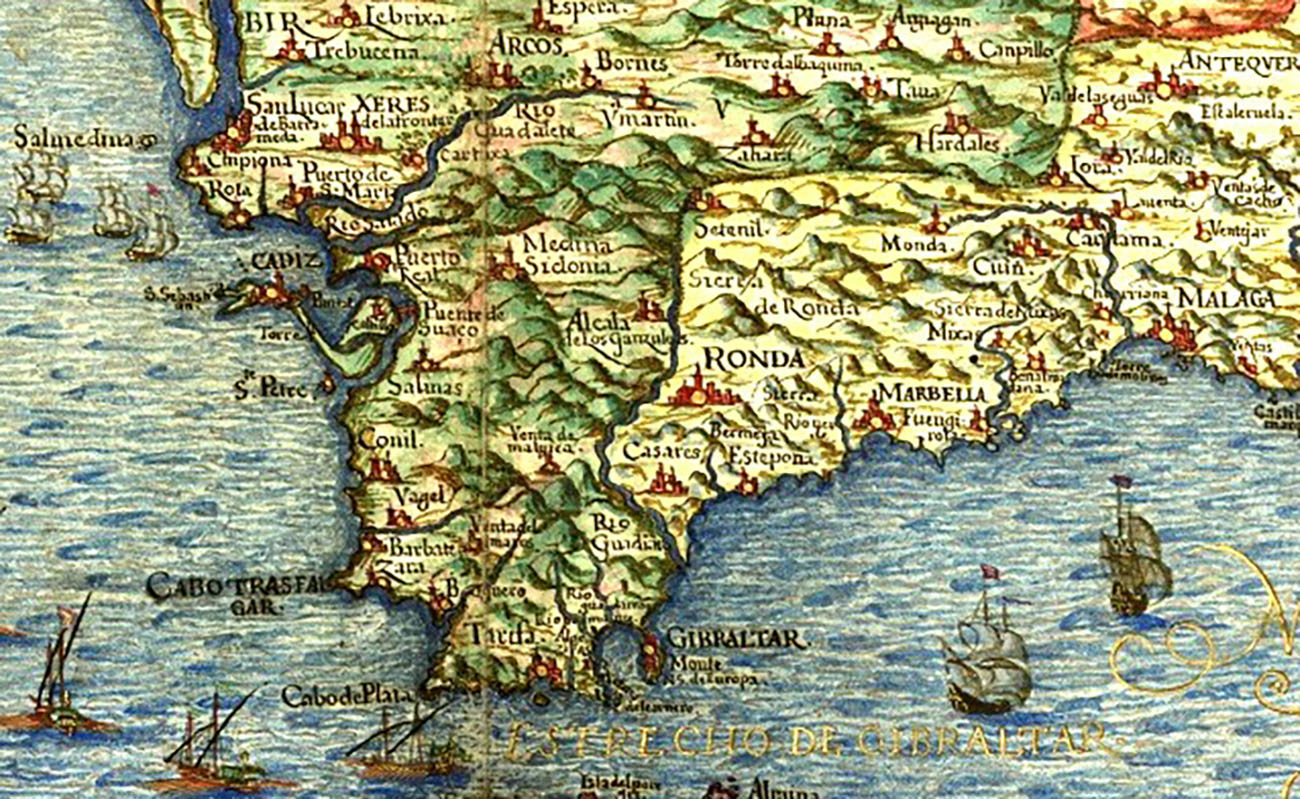

When it comes to guitar, the key to Seville’s rich school of toque was an artist who was not very well known until recently: Paco El Barbero. Even his birthplace was unknown, until we researched this a while ago and found out the he was from Sanlúcar de Barrameda. He arrived in Seville in 1881, when Silverio opened his café cantante on Rosario street. He settled in this city and had an academy in Seville’s San Esteban district, plus a tabanco flamenco on Plata street, in the Campana neighborhood where Manuel de la Barrera and his favorite student, La Campanera, had an academy of baile some years before.

Seville was a city of cantaores and bailaores, but not many guitarrists. Maestro Pérez and Maestro Robles were the most renowned in that era of the café cantantes, plus others such as Monterito and Baldomero Ojeda. Thus, the arrival of Paco el Barbero in Seville (and also of Antonio Sol and Javier Molina, from Jerez), was crucial in the formation of the so-calle Seville school of toque. Antonio Moreno was from Córdoba, although he grew up in Seville, and Currito el de la Jeroma, from Jerez, also arrived in the capital of Andalusia as a teenager, and that’s where he lived until his death. When Niño Ricardo was born in 1904, Seville was already a superpower not only in the making of guitars, with world-renowned luthiers, but also in the quality of its guitarists.

Since a few years ago, the intermingling of flamenco artists from different provinces has been creating a rich, global flamenco. There is a new generation of flamenco artists in all areas of flamenco (cante, baile and toque) from different provinces of Andalusia. Have you already noticed the amount of flamenco artists from Huelva these days, cantaoras such as Argentina and Rocío Márquez and cantaores such as Arcángel, Jeromo Segura and Jesús Corbacho? They are not singers of fandango as in earlier generations, but performers with a wide repertoire, well versed in the cantes of Cádiz, Jerez, Córdoba and Málaga.

I’m pessimistic by nature, but nowadays there’s a roster of great flamenco artists in all its areas who will move this art forward. It’s normal that we miss the great stars of the old days who are no longer with us, this is something that has always happened and will keep happening. Yet, the new generations always take over, sooner or later, and flamenco nowadays has a good quarry of artists. I don’t mean the new artists that are already well-established, but younger ones, new cantaores such as El Boleco, El Purili and Manuel de la Tomasa, among others who are also doing their part.

Flamenco’s cross-pollination continues, and flamenco gets refreshed.

Translated by P. Young