That ‘Quincena Flamenca’ in Seville

History must be told as it was. The Bienal had a forerunner, a festival of flamenco and Andalusian music.

A few days ago, the current director of the Bienal, Antonio Zoido Naranjo said, in an interview published in the Correo de Andalucía newspaper, that before the Bienal de Sevilla existed, “flamenco was [just] something with two chairs, one for the cantaor and another for the guitarist”, and we told him that this was not true. Keeping with the topic of the so-called best flamenco festival in the world, let’s remember today that the Bienal was a copy of a previous festival of Seville, the Quincena de Flamenco y Música Andaluza (Fortnight of Flamenco and Andalusian Music), first held from December 3rd to December 16th, 1979.

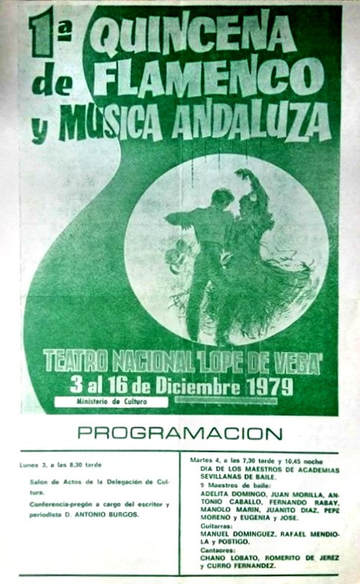

The first edition of the Bienal took place in the spring of 1980. I have the poster of that first Quincena (seen here), which took place in the Lope de Vega theater, and if we take a closer look at the program, you’ll notice that the format and concept were the same that José Luis Ortiz Nuevo later brought to the Bienal. Why has nothing ever been written about this, as far as I know? Because we, the people of Seville, are forgetful, and the historians of the Bienal are a bit absent-minded.

I experienced that 1st Quincena de Flamenco y Música Andaluza when I was just 21 years old, and I remember that the opening speech was given by the great journalist and writer from Seville, Antonio Burgos, in the Assembly Hall of Seville’s Town Hall Cultural Delegation. The opening speech of the 1st Bienal was made by the poet from Granada, Luis Rosales, in the Lope de Vega theater. But let’s continue with the program of this first Quincena. On Tuesday the 4th, two performances, Día de los Maestros de Academias de Baile (“Day of the Teachers of Academies of Baile”), with Adelita Domingo, Juan Morilla, Antonio Caballo, Fernando Rabay, Manolo Marín, Juanito Díaz, Pepe Moreno and Eugenia and José. Cantaores: Chano Lobato, Romerito de Jerez and Curro Fernández. In the guitars, Manuel Domínguez, José Luis Postigo and Rafael Mendiola. On Thursday the 6th, Día del Piano Flamenco, with Arturo Pavón and Felipe Campuzano.

The next day was the turn of the concert guitar, which in those days was enjoying glorious moments with the revolution of Serranito, Paco de Lucía and Manolo Sanlúcar. On that day, Día de la Guitarra Flamenca, Enrique de Melchor and one young Rafael Riqueni performed in the first part, and an exuberant Paco Cepero performed in the second part. Friday the 7th was the turn of cante, with Naranjito de Triana, Paco Taranto, Chocolate and Manolo Mairena, the guitars of El Poeta and Manuel Domínguez El Rubio, and the baile of Ana María Bueno.

Saturday the 8th was Día del Cante y Baile de Cádiz with Paquera de Jerez, Beni de Cádiz, Camarón de la Isla, Terremoto de Jerez and Juanito Villar in cante, La Tati in baile, and Niño Jero and Tomatito in toque. How much would such lineup be worth today? And what about this one, on the 10th, Día de la Antología del Cante y el Baile, with Fosforito, Lebrijano, José Menese, Enrique Morente and Turronero. In baile, the great Trini España, and in toque, two prodigies, Juan Habichuela and Pedro Peña.

Being a festival of “Flamenco and Andalusian Music” (wasn’t flamenco considered Andalusian, then?) there was room for other music and dance genres, such as sevillanas. Sunday the 9th was Día de los Cantes Rocieros, with Los Romeros de la Puebla, Los Marismeños, Los Amigos de Gines and El Pali. The 10th was Día del Rock Flamenco, with Guadalquivir, Fragua and Pata Negra. The great Juanita Reina performed on Thursday the 13th, Friday the 14th and Saturday the 15th with the Estudio de Danza de Caracolillo (Caracolillo being her husband).

Tuesday the 11th had been Día de los Cuadros Gitanos, with Los Montoya, Los Farrucos and Manuela Carrasco. Would it be possible to put more art in a theater? Finally, on the 16th, the closing day, was Día Dedicado a los Grandes Maestros del Baile with (wait for it…) Pilar López, Curro Vélez, Rosario, Enrique el Cojo, Matilde Coral and Rafael el Negro. In cante, Chano Lobato, Romerito de Jerez and Curro Fernández, and in toque Manuel Domínguez, Rafael Mendiola and José Luis Postigo. That was it!

Do you know who created this festival that made history, even if only six editions took place? The greatly missed flamenco critic Miguel Acal, who was the adviser in flamenco matters to the then-director of the Lope de Vega theater, José Luis Ortiz Nuevo. Miguel Acal was the one who programmed this 1st Quincena de Flamenco y Música Andaluza, and its following editions from 1980 to 1984.

The Bienal was born on March 27th, 1980, copying this new format, but adding lectures by Félix Grande, José Monleón and Manolo Barrios, round tables, and also the contest Giraldillo del Cante, won in that first edition by Calixto Sánchez with full merits. In that first Bienal there were also sevillanas (and even a pregón, by Antonio García Barbeito), and also Gualberto’s rock flamenco, among other things, but everything under the label “flamenco”, something which has always been controversial, regarding what is and what isn’t arte jondo.

It’s possible that this festival, the Quincena, was born as the Bienal was being created, due to the commercial perspective of José Ortiz Nuevo and his loyal squire Miguel Acal Jiménez’s. Yet, history must be told as it was, and this, ladies and gentlemen, is history. That is, the Bienal had a forerunner, a festival of flamenco and Andalusian music programmed as we’ve seen.

Translated by P. Young