Squandering talent

What does it mean to sing well? I’m asking this question because it’s very hard to answer. We have great singers in our days, but this doesn’t mean we now have the best singers in history, although that’s just my opinion. Naturally, it’s impossible to know how people used to sing before recording technology existed, but we can have an

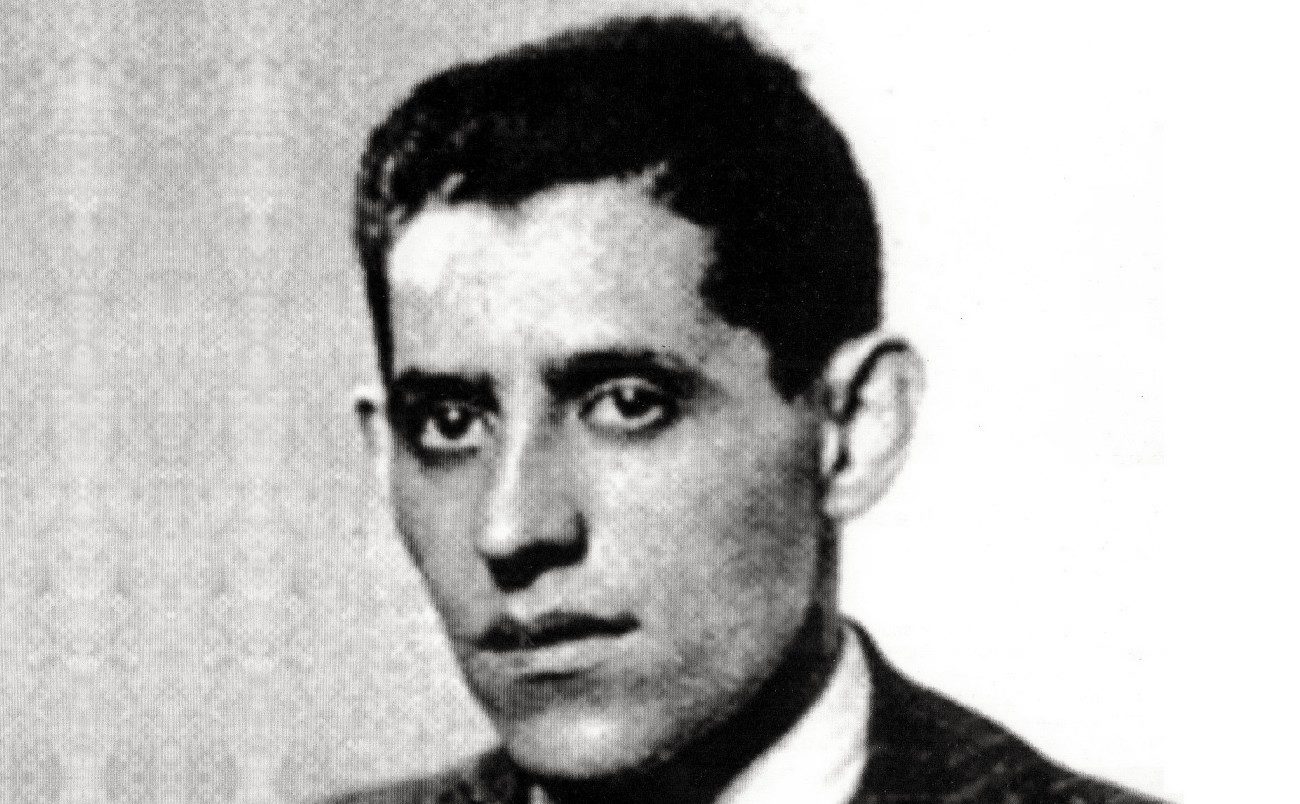

What does it mean to sing well? I’m asking this question because it’s very hard to answer. We have great singers in our days, but this doesn’t mean we now have the best singers in history, although that’s just my opinion. Naturally, it’s impossible to know how people used to sing before recording technology existed, but we can have an idea by listening to those old wax cylinders. I think Chacón probably sang like Silverio, and Manuel like Tomás El Nitri, even as he never listened to him. Oddly, El Nitri died on the same street in the San Miguel district of Jerez, Álamos Street, where Torres was born, although El Nitri died two years before Tomasa Loreto Vargas gave birth to Manuel.

Talking one day with an old cantaor about this topic, taking advantage of talent, he told me that there were cantaores who wasted very good voices, while there were others who were able to make good use of their limited talent. He used himself as an example, and I objected when he said he didn’t have much innate talent because he didn’t have a great voice, even as his voice was great. We shouldn’t confuse talent with the strength of the voice. Every cantaor has a collection of talents. Having a good voice is a talent, but there are other talents such as having good tuning, vocalization, rhythm, steadiness…

Fregenal was a big fan of Vallejo, but he believed he squandered his voice in the endings (remates) and made the verses unnecessarily long. Fregenal also boasted of having good lungs when it came to the remate of his personal fandangos, and almost everyone who tries to sing them end up failing miserably. This cantaor from Fregenal de la Sierra was a prodigy of technique and was able to retain his breath in an astonishing way, which allowed him to finish off unbelievable verses and finish his fandangos without ever messing up the melody. He was a clear example of someone who knew how to take advantage of his talent.

In our days there are cantaores, particularly young ones, who make good use of their technical and vocal abilities. Rancapino Chico is a clear example, and also his father, who still sings and, even as his voice is very worn out, is still able to link verses like in his heyday. And little Alonso is a true prodigy: without having a big voice, which is not necessary, he’s able to finish his cantes admirably, moving everyone who listens.

Other cantaores waste their talent, for example, singing palos that are too demanding and not suited to their voices. Others sing “blowing”, that is, releasing too much air at once in one verse, and then when they have to finish it, they struggle, beating their chests with great drama. They call it to fight with cante (as in daring or challenging cante). If the cantaor sings properly, with a good technique, taking advantage of their abilities and talents, it’s not necessary to fight with cante. There’s a story of one cantaor who asked Pepe Marchena to work in his company, and he kept telling him that he was able to fight all cantes. When Marchena listened to him and saw his performance, he told him “you fight so much with these cantes that they get mad at you”.

Singing well is very difficult, not to say impossible. And in some periods of flamenco history there have been such good singers, such as Chacón, Pastora, Manuel Torres, Cayetano Muriel, Mojama and Vallejo that we’re eager compare them with today’s cantaores. Incidentally, in our days there are a dozen young cantaores who sing wonderfully, regardless if they’re properly using their talent or not.

Translated by P. Young