Paco Mármol, flamenco poet

One of my great hobbies is the so-called copla flamenca: lyrics of cante jondo. I not only like writing them, but also reading other people’s lyrics. I greatly admire Ferrand, Manuel Machado, Francisco Moreno Galván, Fosforito (this cantaorfrom Puente Genil is one of the best lyricists of the 20th century), Rafel Montesinos, Antonio García Barbeito and many others. Writing a simple three-verse soleá is not easy, particularly

One of my great hobbies is the so-called copla flamenca: lyrics of cante jondo. I not only like writing them, but also reading other people’s lyrics. I greatly admire Ferrand, Manuel Machado, Francisco Moreno Galván, Fosforito (this cantaorfrom Puente Genil is one of the best lyricists of the 20th century), Rafel Montesinos, Antonio García Barbeito and many others. Writing a simple three-verse soleá is not easy, particularly one suitable for singing and capable to express its intended meaning. Because, as I wrote many years ago, “en tres versos bien escritos, nos cabe toda una vida, y algo más que lo vivido” (“in three well-written verses, we can fit a whole life, and even something more”).

I have mentioned several famous authors, but there have been probably hundreds of other authors throughout flamenco history who have often remained anonymous. Those were the ones who created the lyrics sung by El Planeta (A la luna le pido), Silverio (A la mala lengua), Chacón (Engarzá en oro y marfil), Niña de los Peines (Quisiera yo regenar) or her brother Tomás (En el patio de Caifás), all lof them renowned flamenco stars. Who knows the names of the writers who created such literary wonders, now part of the traditional repertoire of cante jondo?

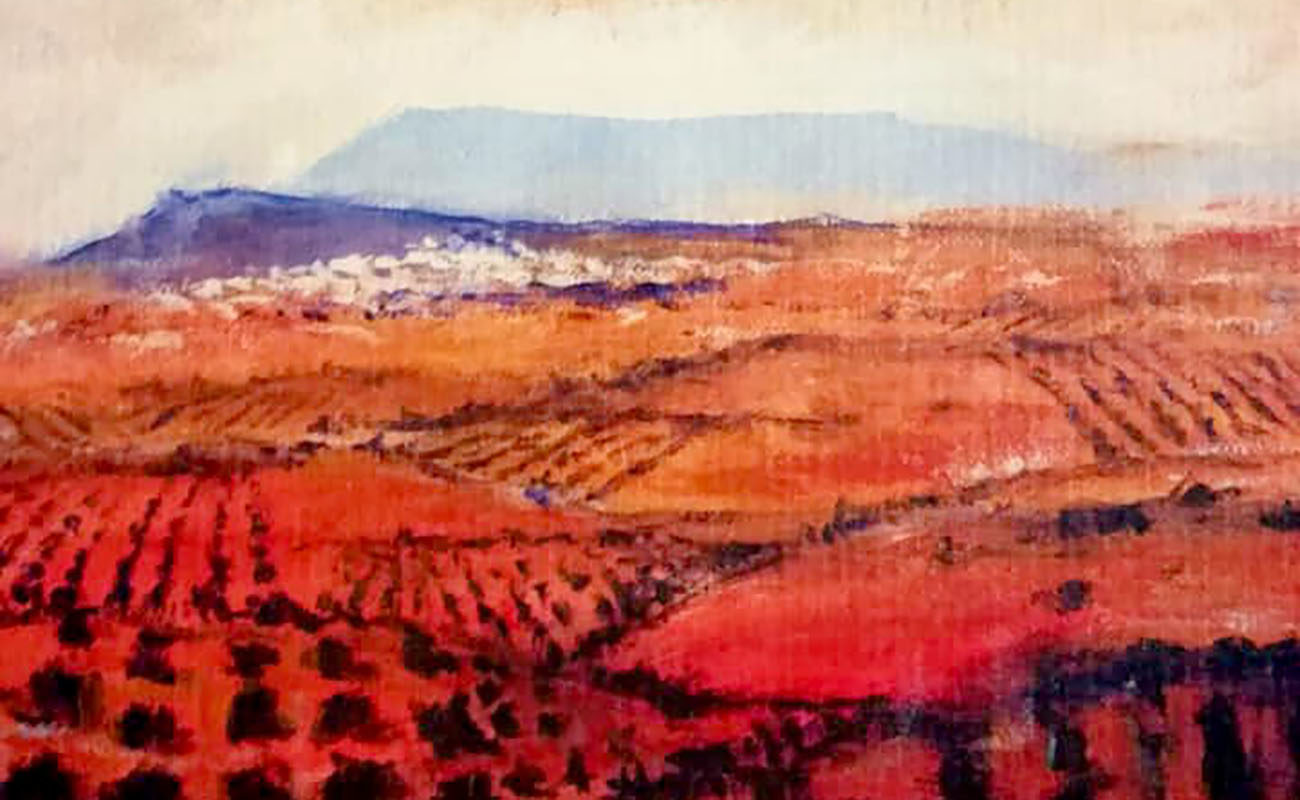

Francisco Mármol Moreno is a popular poet from Puebla de Cazalla, a very flamenco town in Seville province, the birthplace of Niña de la Puebla, Lola Lucena, José Menese, Miguel Vargas, Diego Clavel and Manuel Gerena, among other less famous cantaores. He is a great cante aficionado and very well-versed in flamenco, something which I believe is essential to write good flamenco lyrics. The lyrics of Paco (as he’s known among his friends) are totally suitable for singing. These lyrics are not far removed from the places where cante is performed: peñas, taverns or the gatherings of friends. His lyrics have the scent of his town, of the wet sawdust in the taverns or the marinade of Bar Central, a bar in his town.

Francisco has already published five books of lyrics, including his latest release, “Letras flamencas de la campiña morisca”, which I’ve read with the same interest as I’ve read the previous ones. Once again, I’ve been pleasantly surprised by his great ability to write flamenco lyrics. We all know that he’s currently enjoying a well-deserved retirement, so he certainly has the time, but even so, Paco is a lyric-creating machine. I’m sure this is because flamenco lyrics are his lifelong passion.

I admire Paco’s simplicity and the fact the such simplicity comes to life in his poetry. Simplicity as in devoid of embellishments, not as in “plain”. If he were a cantaor instead of a poet, he would be like Miguel Vargas or Diego Clavel: natural like the evening wind in the countryside.

It’s hard to pick a favorite lyric from this book, because it has hundreds of them for many different palos, but if I had to choose my favorite, it would be this one:

Cómo han dejao el Cerro

de los Dolores,

los olivos pa cotos

de cazaores.

It’s a liviana in the style of Moreno Galván and typical of La Puebla and of Paco Mármol himself. It can be loosely translated as “Look how the olive groves have left Dolores Hill, to give room for the hunting grounds”. It’s simple and deep, subtly denouncing, without any hatred, a sad reality of the countryside.

I fully recommend this book. Congratulations, my friend!

Translated by P. Young