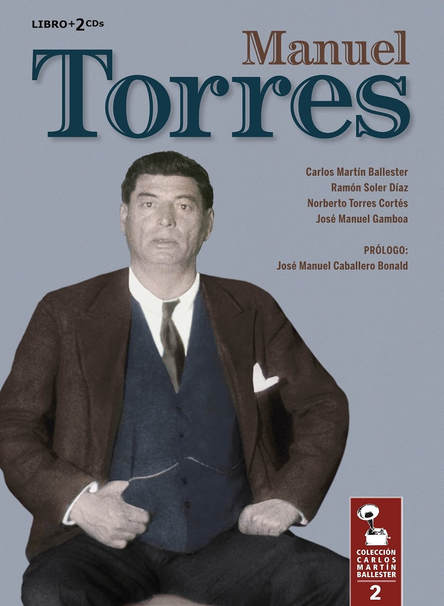

Manuel Torres in Seville

Next Friday at Casa de la Provincia, in Seville, the second volume in the Colección Carlos Martín Ballester will be presented. This volume is devoted to the great Manuel Soto Loreto, the brilliant Manuel Torres (b. Jerez 1880, d. Seville 1933), without any doubt one of the great stars of cante in the 20th century. Thus, a genius, an artist without whom cante jondo in Seville cannot be conceived,

Next Friday at Casa de la Provincia, in Seville, the second volume in the Colección Carlos Martín Ballester will be presented. This volume is devoted to the great Manuel Soto Loreto, the brilliant Manuel Torres (b. Jerez 1880, d. Seville 1933), without any doubt one of the great stars of cante in the 20th century. Thus, a genius, an artist without whom cante jondo in Seville cannot be conceived, is back to the capital of Andalusia, where he arrived in the late 1800s, enticed by the charms of the bailaora Antonia La Gamba (from Cádiz), cante and cockfighting. It hardly gets more Gypsy than that.

It’s peculiar that when El Majareta (his nickname in Seville) registered in the city’s registry, he made a point that his occupation showed up as “cantaó”. Not “cantante” or “cantador” (the usual words for “singer” in Spain at the time), but “cantaó” with an accent in the “o” (a term which would become exclusively flamenco). He came from Jerez and in those parts cantaores were indeed cantaores and not “cantantes” (“singers”). That was the case with his maternal uncle, Joaquín Loreto Vargas, Joaquín Lacherna (fishmonger and seguiriyero) and also Loco Mateo, Antonio Frijones, Diego and Antonio El Marrurro, Paco La Luz and Tomás el Nitri, who had been born in Puerto de Santa María but had settled in Jerez.

How was the flamenco scene in Seville when Manuel Torres (or Niño de Jerez, as he was also known by the aficionados) arrived in that city? It was teeming with artists, cafés, flamenco halls, tabancos and dance academies. It had two main hubs of good cante, Triana and La Alameda de Hércules, and also had great cantaores from Seville and elsewhere who lived and performed in the city: Chacón, Fosforito el de Cádiz, Escacena, El Portugués, La Serrana, Juan Dulce, Ramón el Ollero, Pepe Villanueva, El Macareno, Miguel Macaca, Pepa de Oro, Enriqueta la Macaca and a long etcetera. New, young talent also started to achieve renown, such as Niña de los Peines, Manuel Vallejo, Manuel Centeno, Pepe el de la Matrona and Bernardo el de los Lobitos.

Manuel Torres revolutionized cante jondo (Gypsy cante), because it had become sweet and refined in Seville due to certain artists such as Silverio, La Serneta, El Canario de Álora, Chacón, Fosforito and Pepa de Oro. Manuel didn’t sing in falsetto, but with his natural voice and with a Gypsy sound which was starting to disappear even in Triana. Thus, when he began performing at El Filarmónico or El Novedades cafés, or at the tabancos in La Alameda, Niño de Jerez’s farrucas, tientos and marianas were the talk of the town. Manuel’s seguiriyas gitanas, though, were reserved for the private gatherings of cabales (flamenco connoisseurs).

He brought to Seville a new wat to perform the cante gitano of Jerez and all of Cádiz province, influenced by his uncle Joaquín, Enrique el Mellizo and Francisco la Perla, who was from Triana but had been living in Jerez from an early age. He brought that essence, but he had his unique style, a way to sing shortened, linked verses, with a natural voice, with pellizco, scratches and convulsions. Manuel didn’t extend the verses, he rather swallowed them, causing an irresistible effect in those who listened to him. He had duende, which is a gift and not something that can be learned. El Majereta was able to confer an incredible flamenco depth even when singing simple campanilleros, something only a genius can achieve.

When geniuses approach an art form, they contribute their ingenuity and talent, and the art form is forever changed. That’s what happened with Manuel Torres: he arrived, sang with his own imprint, full of Gypsy essence, and changed the history of cante. He and Chacón changed cante forever, and they did it in Seville. That’s why I celebrate the return of El Majareta to the city which welcomed him for over thirty-five years.

Translated by P. Young