Life and soul in lyrics

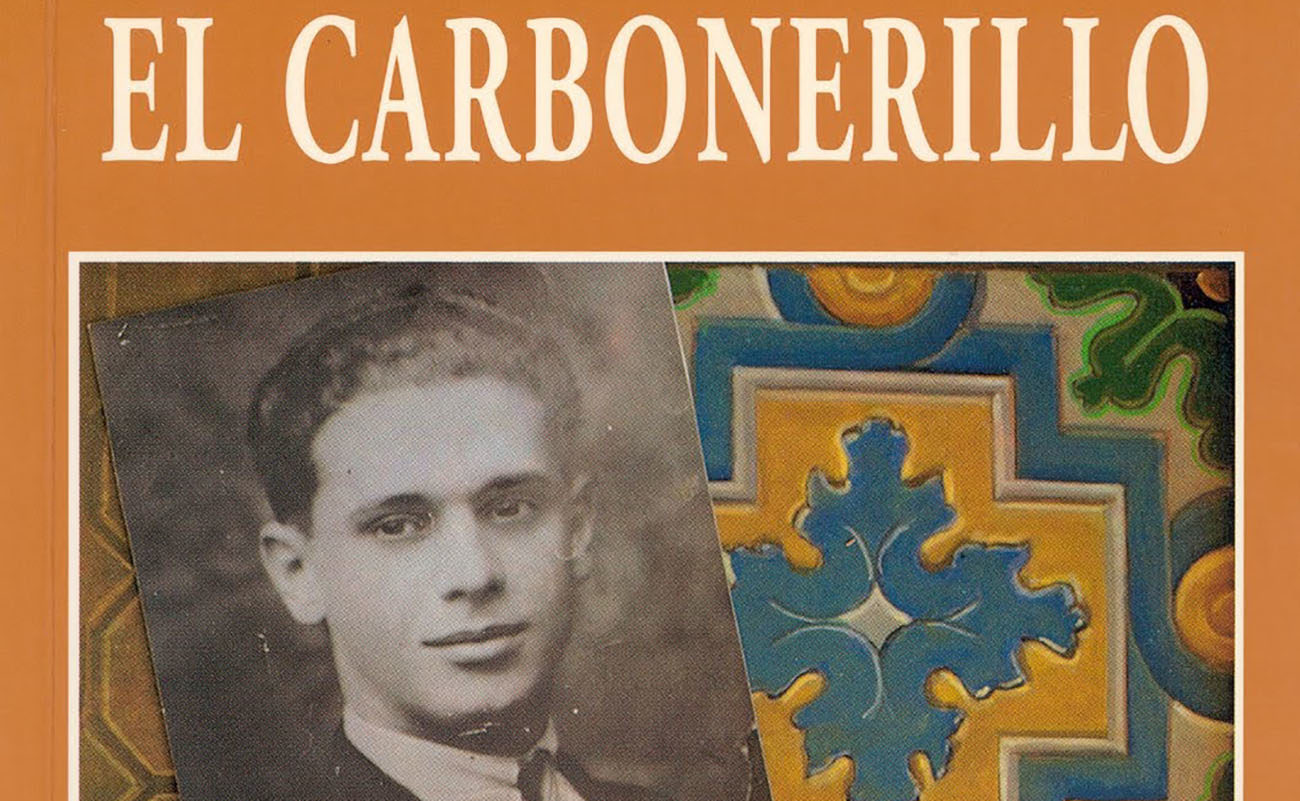

I still prefer cante from a particular time period, from the early 20th century to the 1970s, because it’s possible to get to know virtually all artists in those seventy years through the lyrics in their cantes. El Carbonerillo (Seville, 1906-1937), used to tell his life story in his fandangos, although we must point out that not all the lyrics he sang were written by him,

I still prefer cante from a particular time period, from the early 20th century to the 1970s, because it’s possible to get to know virtually all artists in those seventy years through the lyrics in their cantes. El Carbonerillo (Seville, 1906-1937), used to tell his life story in his fandangos, although we must point out that not all the lyrics he sang were written by him, but also by authors who knew him well, knew how he felt and how he lived his life, sometimes bitterly, others happily. Topics such as his mother, love and heartbreak were very important for this cantaor.

His mother, Rocío García Cuesta, born in Seville, was a tough woman who raised several children in difficult times. She only had two male children, El Carbonerillo (Manuel Vega García) and Isidoro, who never had much to do with cante. Rocío felt special love for his Manolito, a cute kid who had been born with the gift of cante. Anita, one of the two sisters of Carbonerillo that I met, told be that he already sang when he was 5 years old, and when he was 7 he would entertain the workers at the Pickman textile factory (where she and her other two sisters worked) singing from the top of a table. At lunchtime, they’d put him on a table to sing fandangos de El Colorao de La Macarena, or some guajira by Manuel Escacena.

El Carbonero was soon acquainted with heartbreak, when he was a teenager, something quite common in that period of our lives. He had a girlfriend who soon dumped him and hooked up with a widower, according to the testimony of people I was able to talk when I was writing a biography of this cantaor from Seville. That heartbreak took out of his chest the most harrowing fandangos and the most desperate soleares.

Y te echaste a reír.

Me viste un día llorar

y te echaste a reír.

Yo no te quise contar

que aquel llanto era por ti

Al verte tan desgraciá.And you started laughing

One day you saw me crying

And you started laughing

I didn’t want to tell you

That I cried for you

When I saw you were so miserable.

I can imagine this great cantaor crying for that woman, and she laughing at him in his presence, as it happened more than once. In one of those occasions he even slapped her in public, in a bar, according to the testimony of people in his circle whom I met.

That’s what cante jondo is all about, telling things about life. It’s not the same, singing lyrics by someone who has never met us, than singing our own lyrics, or those by someone who knows us well. As another example, Tomás Pavón sang many lyrics by his brother Arturo, who was a good lyricist, although he never took songwriting seriously. Even Manuel Torres sang lyrics by Arturo, since they were good friends. Yet, Tomás also sang some of his own lyrics, two of them never recorded, por soleares:

Me voy a la calle Feria,

que está cantando Pacuco

las coplas de La Sarneta.I’m going to Feria street

There, Pacuco is singing

The verses of La Sarneta

Pacuco, born in Seville, was a boyfriend of La Sarneta de Jerez, who also lost his head for this beautiful artist, to the point that he slashed his own throat with a barber’s razor, although he survived and sang with his voice badly damaged by his injury. El Cuco, uncle of Caracol (brother of his father) did the same thing because he fell madly in love with Pastora Imperio, who corresponded at first, but then rejected him, leaving him ruined and crazy. In a state of insanity, one day he went to a hardware store, bought a barber’s razor and cut his head off with a deep slash.

Every year I get dozens of new cante albums and I seldom hear new verses which speak about the artists’s lives, or about their feelings. These are very well-produced albums, with excellent sound and all kinds of technical wizardry, yet they feel empty.

Hice de mi vida un sueño,

luego me dijo una rosa

que los sueños, sueños son,

y a otra cosa, mariposa.I turned my life into a dream

Then a rose told me

Dreams are just dreams

So, fly away, butterfly.