Grandpa and Seville’s apathy

-Grandpa, I’ve just came back from Vienna and was amazed at how much they care for their artists, their monuments and their history. We have a lot to learn here in Andalusia, don’t we? -You mean, regarding the monuments to artists? -Yes, among other things, grandpa. -In Seville there are monuments honoring Antonio Mairena, Manolo Caracol, Niña de los Peines, Pastora Imperio, Niño Ricardo, Naranjito de Triana and Pepe Peregil.

-Grandpa, I’ve just came back from Vienna and was amazed at how much they care for their artists, their monuments and their history. We have a lot to learn here in Andalusia, don’t we?

-You mean, regarding the monuments to artists?

-Yes, among other things, grandpa.

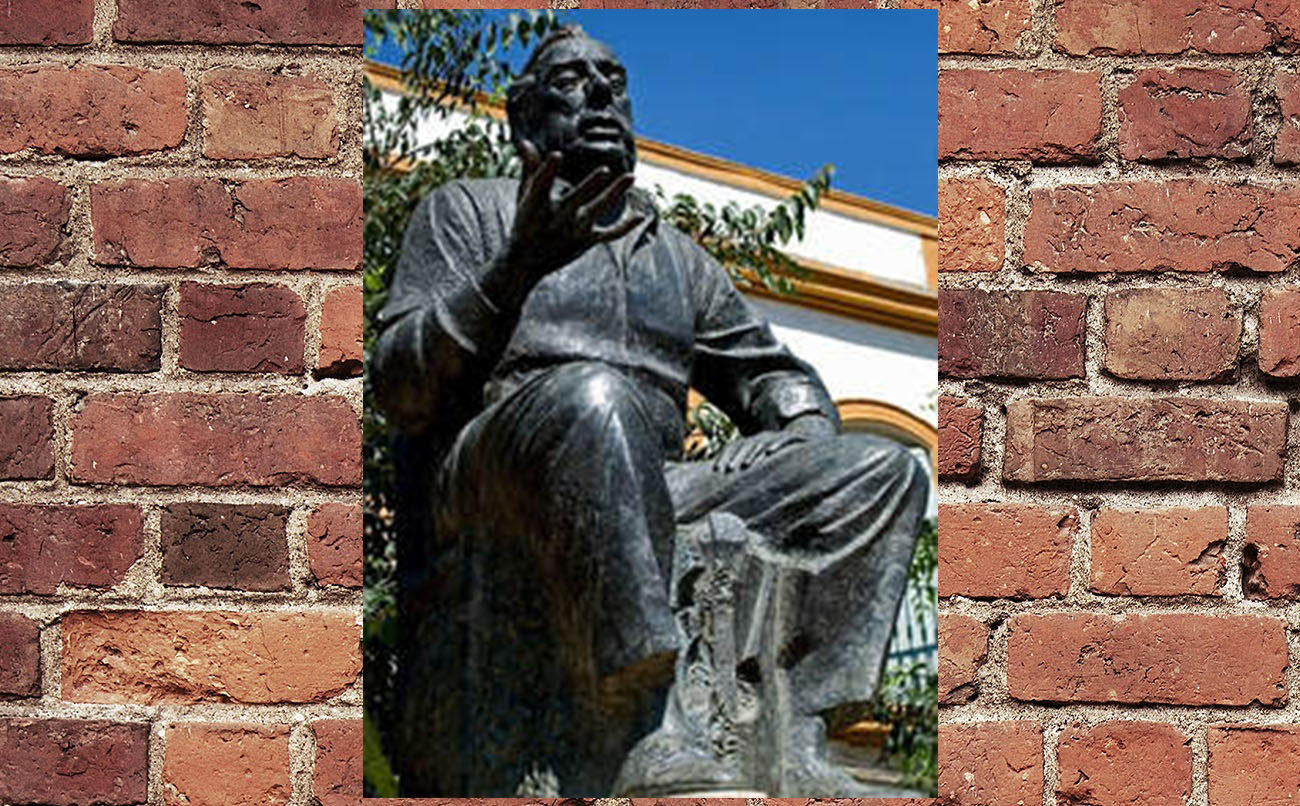

-In Seville there are monuments honoring Antonio Mairena, Manolo Caracol, Niña de los Peines, Pastora Imperio, Niño Ricardo, Naranjito de Triana and Pepe Peregil. There is nothing for Manuel Vallejo, who was one of the greatest, and the same goes for Silverio, who was basically the father of cante, kind of.

-What’s your take on this apathy?

-It’s typical of Seville. Look, Seville is one of the main cradles of flamenco, yet it has no archive center about its history. Incredible, isn’t it? That would be unthinkable in other cities. In the streets and parks of Vienna, from where you’ve come from so amazed, you can find monuments completely integrated with the urban landscape. Could you imagine the capital of Austria without a monument to Johann Strauss? Yet, as you can see, there isn’t even one peña named after Silverio in Seville, the city where he was born and where he created a musical revolution. This was also the city where he died, although his remains were lost. It’s truly a pity, Manolito.

-I was particularly impressed at how well they care for the monuments to their artists, grandpa.

-They’re very cultured, being such an ancient city with an unparalleled musical legacy. I remember that a few days after they put up the statue of Caracol in La Alameda, people would hang up stuff in his right arm, like panties and such, and someone even put a bottle of beer in his hand. The statue was often covered in bird droppings and littered with garbage. It was a real shame.

-Yet, Seville is also an ancient city with an important cultural history, isn’t it?

-Yes, without a doubt, but if someone were to put a monument honoring Silverio in La Alfalfa, the neighborhood where he was born, many locals would complain and others would wonder what on earth that man did in Seville, because, although you may find this hard to understand, the people of Seville is very illiterate when it comes to flamenco. The locals don’t know the history of this ancient art, and this is unforgivable.

-They don’t know its history, you say? Grandpa, that’s pushing it.

-No, they don’t. They know about modern flamenco, but have no clue about the 1800s, which is when it all came together. The don’t know who was El Burrero or Juan de Dios, La Campanera or Petra Cámara. They’re unaware of Maestro Otero’s important role in dance, in baile, or that of Miguel de la Barrera. That goes to show the scant knowledge about flamenco culture among the people of Seville, in general.

-You’ll be flayed alive, grandpa.

-For telling the truth?

-Yes, for telling the truth. You’re too straightforward, grandpa, you could say things in a different, nicer way.

-To cover up the truth, Manolito?

-It’s not like that, grandpa. Well, we have to get ready for the new year’s celebrations and you seem to be angry at everyone. Where will you spend New Year’s Eve?

-At home, listening to Manuel Torres, whom I love, as you know.

-Happy New Year, grandpa.

-Same, Manolito. Don’t get too drunk.

Translated by P. Young