Gentleman of Triana

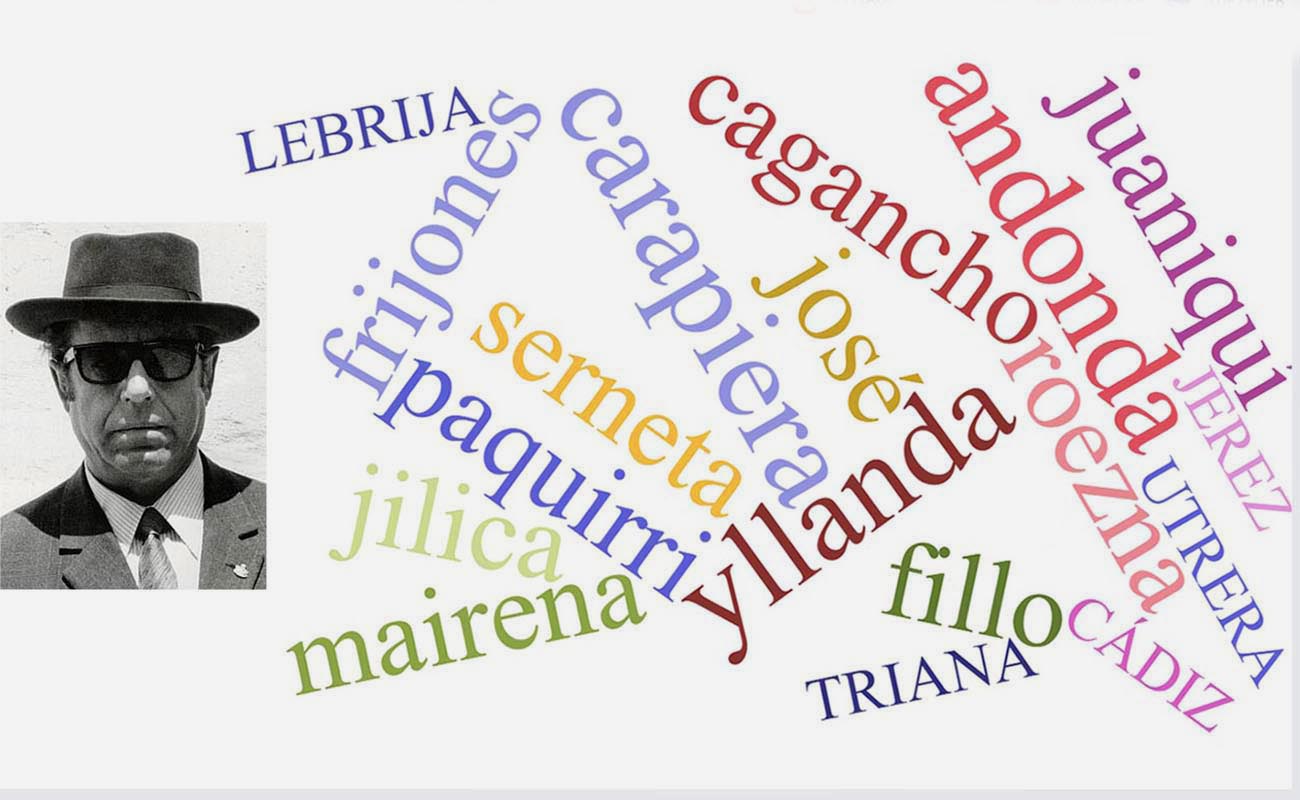

I became well acquainted with José Sánchez Bernal, Naranjito de Triana, and I think of him almost every day for whatever reason.

I became well acquainted with José Sánchez Bernal, Naranjito de Triana, and I think of him almost every day for whatever reason. He was a child prodigy of cante, born on Fabié street in Triana, near Altozano square, Pureza street (formerly known as Larga street) and Betis street (formerly known as Orilla del Río). Naranjo was a full-blooded trianero. Without any doubt, he was the most important cantaor to come out of Triana, because he was a big star of cante and gave Triana more renown than anyone else.

He was born in 1933, a year that often comes up in flamenco history, because it was the year when Manuel Torres and Joaquín el de la Paula passed away, to mention just two famous cantaores. It was also the year when Niña de los Peines married Pepe Pinto (also a cantaor) at the Basilica of La Macarena. At that time, Chacón, Escacena, El Portugués and Ramón el Ollero had already died, City Council had demolished the Café Novedades and the big names in cante were Niña de los Peines, Manuel Vallejo, Niño de Marchena and Manolo Caracol, among other renowned artists.

Naranjito ended his days bitter about flamenco. Rather, bitter about the flamenco world. He visited me many times in my house in Triana (I should say ‘the house I lived in’, instead) and we talked a lot about this topic. He felt that people didn’t acknowledge his worth, despite his long career and his great quality as cantaor. He felt very hurt about this, because he was very smart and knew what that meant. One morning he told me this, in my house:

“I’ve seen great cantaores of Seville to die forgotten, and I don’t want to be one of them. Vallejo himself died alone and very much forgotten. I don’t mean alone as a person, because he never married, but alone as a cantaor. And he was so great, my God. Sometimes I’d seen him at La Alameda, sitting by a table and he would barely have money for one coffee. He would stop by Las Maravillas, on the corner of Trajano street, across Realito’s academy, shrunk like a raisin. I’d ask him things about cante and he’d barely bother to answer. I think he felt disgusted.”

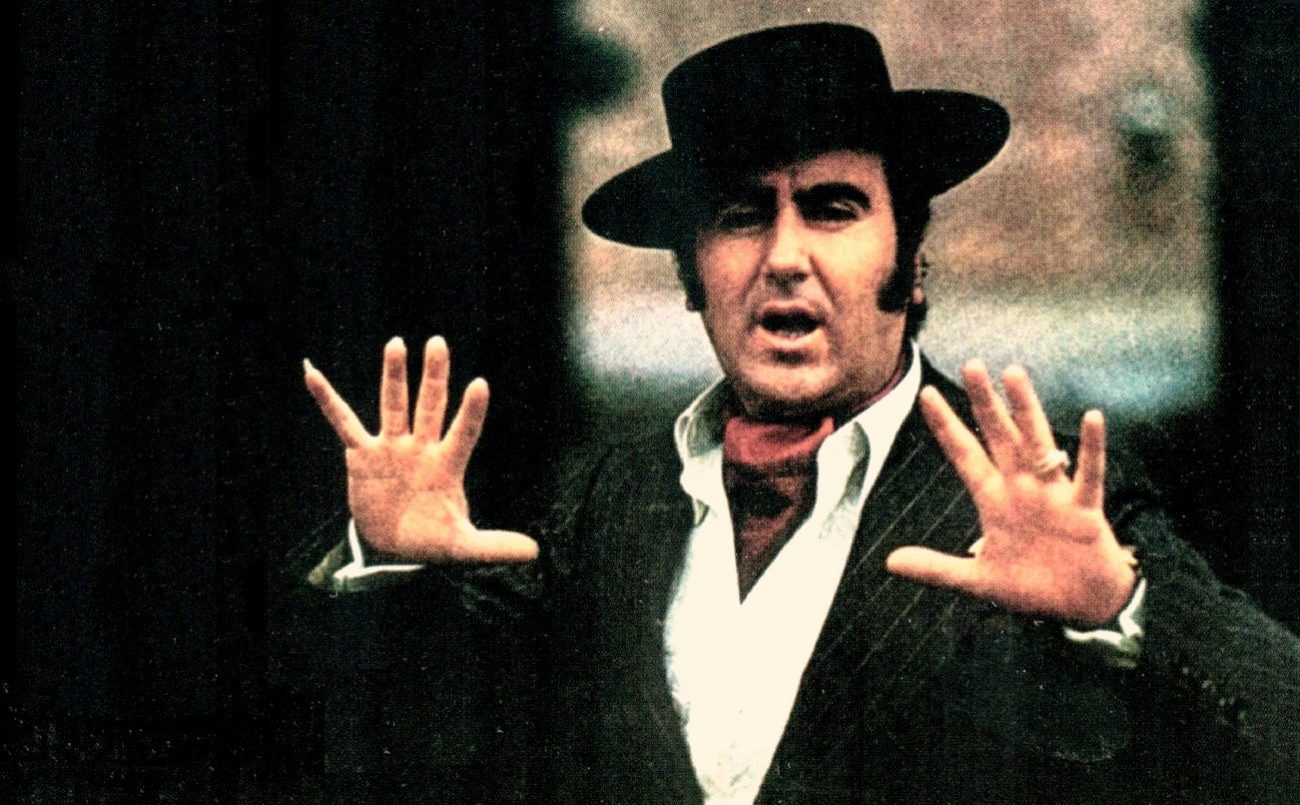

Naranjo didn’t end like that because he made a lot of money and, unlike Vallejo, he took good care of his earnings. He retired from cante because he felt like it, and he did it in style, singing at the Maestranza theater with the best guitarists of that time. He packed the coliseum at Paseo de Colón and left with a bang. No one could understand why a cantaor in full control of his faculties, with an impeccable voice and a good head on his shoulders would retire from cante. Part of the reason was that he was sick and tired of the flamenco world and of some critics who even offended him.

“I don’t understand some critics, Manolo. I get a standing ovation at five in the morning in a festival, but in the newspaper review they put the picture of artists who made people get up and head to the bar as soon as they got on stage. Those things burn me out.”

Today is not the anniversary of his birth, or of his death. I just though of him yesterday and I felt like writing about someone who was a great friend and whom I admired and still admire as a cantaor and as a person. Naranjito, a gentleman of Triana.

Translated by P. Young